The Leaves Turn Over

Monday 2 October 2023

The Federal Reserve’s rate hike campaign appears to be over. While it’s too soon to forecast when rates will fall again, investors in renewables projects should probably have an eye open now to that eventuality. The FOMC’s last rate hike occurred on July 27th, after holding rates steady at the prior meeting in June. At the September 20th meeting, they once again held. That lack of further action has landed forcefully into the fed funds futures market, with the probability of any further rate hikes diminishing quickly. To put a cherry on top of the emerging consensus, the always hawkish John Williams of the New York Fed commented that the peak in fed funds has finally arrived.

Critics of direct air capture technology makes a number of valid points. But, the position of The Gregor Letter is that we should invest and pursue DAC regardless. It’s true: oil and gas companies and other industrial sectors could adopt DAC technology as a means to greenwash their own emissions. Worse, if the US offers poorly designed subsidies and incentives around DAC, this greenwashing would proceed with tax payer support. And that’s not good. Finally, there is the very sobering fact that because DAC uses so much energy to operate, we risk running in place if we launch a bunch of machines that capture CO2, but burn CO2 all the while through their demand-pull on the powergrid.

These considerations are particularly salient at the moment because the US government is making moves to support the technology. Last month, the Energy Department announced prize money of $1.3 million, out of a $3.7 million dollar total, to 13 semifinalists who produced solutions for CO2 removal. This follows a more substantial $1.2 billion announcement to fund DAC demonstration projects in Louisiana and Texas.

The missing element however in current DAC discourse (and this mirrors other faulty framings) is the vision of how DAC would look in its optimal state, in the future. Simply put, if we can affordably build DAC installations, and, we can run those installations on 100% clean energy from wind and solar, then we will take DAC capacity growth all day long, and why not?

Driving an electric vehicle in any US state now creates less pollution than an ICE car. Because duh, of course. Yale Climate Connections has a nice chart up that assesses the fuel mix in each state’s electricity grid, and then compares how the energy mix shakes out for a typical EV against an ICE vehicle. The results are hardly surprising.

To be clear, this is the narrower pump-to-wheel (PTW) accounting rather than the broader well-to-wheel accounting (WTW). In PTW analysis, no consideration is made of all the upstream mining and CO2 emissions required to product an EV. But neither is all the upstream mining to produce natural gas and coal in powergrids, nor oil production, that stands behind the ICE vehicle. Oil and ICE vehicles lose to EV under both accountings, because as you expand analysis from PTW to WTW it blows out the oil/ICE side of the equation also.

The Gregor Letter has serially presented the far more comprehensive WTW accountings for years, updating the data annually from Argonne National Labs. Subscribers can review the archives under that search term to see how this data has evolved.

California will eventually see at least 90% electric vehicle penetration, thus running all the vehicles on half the energy. Incredibly, most people still don’t understand this. As we know, California gasoline consumption has finally entered decline after hanging on to a twenty year plateau, averaging about 14.9 billion gallons of consumption per year. The energy represented by those gallons will be cut in half in its entirely, as every new EV that hits the road in California goes the same distance as an ICE vehicle, on half the energy. And that’s conservative—the cut is at minimum 50%! Don’t let crackpots tell you otherwise, as they scribble on tattered napkins. How is EV adoption going in California? So well, in fact, that the Golden State is starting to mirror the EV growth rates in China, where we regularly describe the uptake as wild, insane, and totally bananas:

China EV market share: 2020: 5.40% 2021: 13.40% 2022: 25.64% 2023: ~28.00%

California EV market share: 2020: 7.73% 2021: 12.27% 2022: 18.73% 2023: ~24.00%

data sources for the above: China CAAM and news outlets that report CAAM data, and, the State of California.

The degrowth movement seems to have not fully understood how much waste from fossil fuel combustion is to be harvested from energy transition. The very definition of a growth problem—population, pollution, commodity extraction—is expressed in the impacts of emissions. But energy transition—which, by the way is largely a capitalist enterprise—will eventually start cutting down the gross volume of primary energy consumption of fossil fuels, representing the bulk of emissions. Why? Because, again, at least half of our energy consumption is lost to waste heat. Accordingly, the volume of actual economic degrowth the movement seeks is going to be largely accomplished through transition itself. Believing otherwise also flies in the face of the Kuznets Curve, or more specifically the Environmental Kuznets Curve.

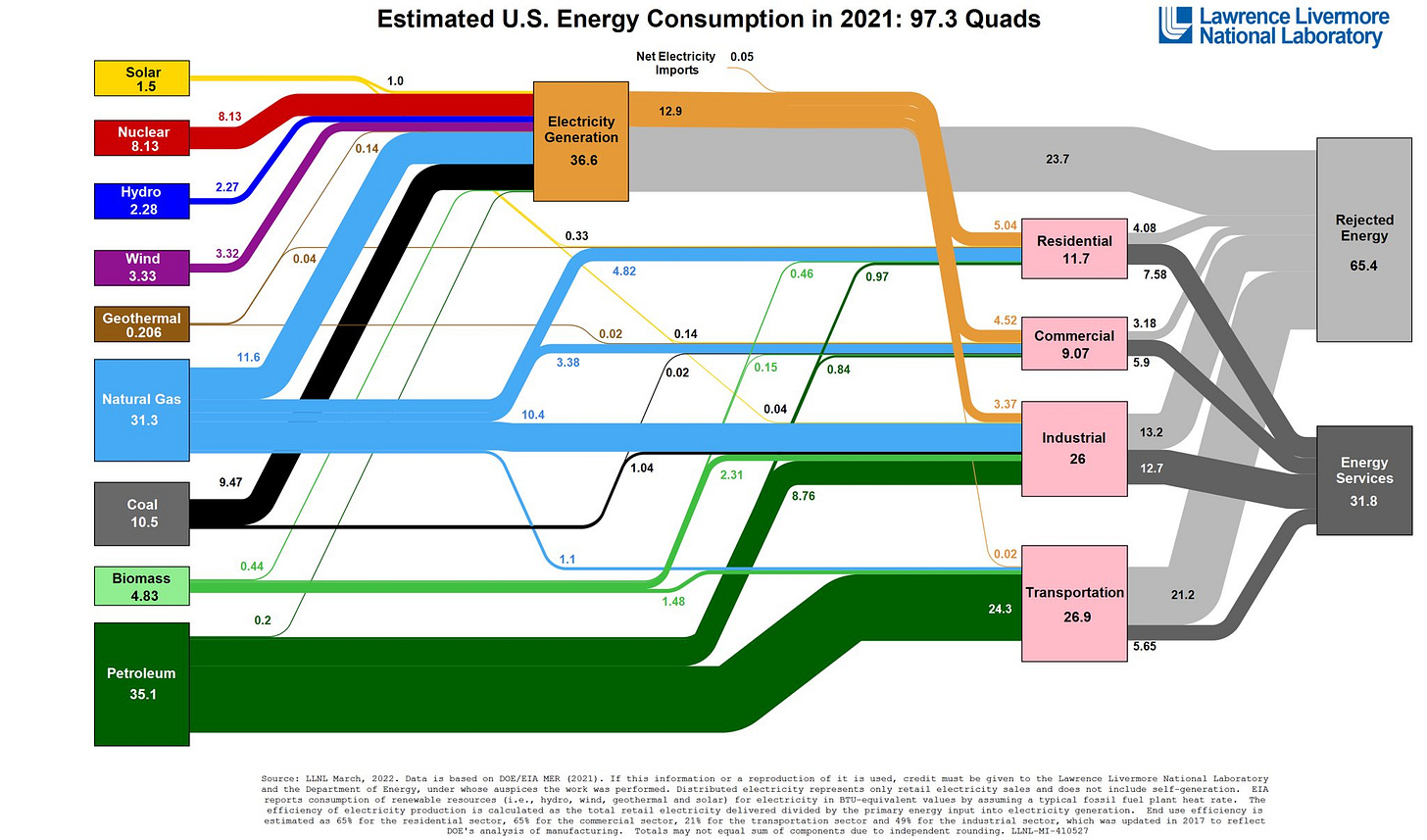

The world consumed 604 EJ (exajoules) of energy in 2022. Without the heavy losses of energy realized through combustion, the world could have run the same economic activity on just 302 EJ. Yeah, accomplishing that will take time and will not be easy. And along the way, population growth and its impact on total consumption of all materials, not just energy, will continue. But energy transition is in fact a way to eventually grow without increasing emissions. If these large blocks of global consumption feel too hard to visualize take a look at this Sankey Diagram from LLNL, showing that, of all the energy the US consumes, combustion dictates that 65% of it is lost, entirely lost, to waste heat. Hint: the volume of energy and emissions we stand to reign in is likely more than 50%.

Hydropower has become increasingly unreliable as the distribution of drought and floods becomes more extreme across the world. In 2021 for example, a sudden 10% output decline in hydro-dependent Brazil triggered a big jump in that country’s consumption of coal and natural gas. Meanwhile the multi-year mega-drought in the US west, which hammered California’s hydro output until last year’s super precipitation event, reduced national output greatly as well. Did last year’s rain and snow event fix the problem? Not really. Yes, California’s hydro output is up this year, but the greater region of the Pacific Northwest is still a problem. The IEA updated the situation this week, reducing total US hydro output by 6% for the year:

Traders habitually overinterpret price action, and nowhere is this more evident than in the oil market. With rising prices of late, the clarion call has predictably gone out that there’s a serious problem with supply meeting robust demand. But when we take a look at the cause, it’s not a demand story at all, but a supply story instead. From the EIA’s latest Short Term Energy Outlook:

All the growth in OPEC spare capacity comes from a five year cutting campaign. Futures markets have spent a long time trying to ignore this supply curtailment. But eventually, especially in the 4th quarter when oil demand typically advances, the supply cuts become part of the landscape. Remember, global demand is still trying to get back to the high of 2019, and may achieve that this year—but not by much. There is no demand story worth writing about, and there will not be the rest of the decade. OPEC’s supply cuts tell you everything they really think about global demand.

The Gregor Letter is considering a name change. We’ll keep you updated as we go along, but the reasons are as follows. The “Gregor” moniker is a carryover from the original Gregor.us website, which now redirects to the newsletter. When few people were writing about energy over 15 years ago, this was not a bad identifier. My name became quickly associated with all things energy, helped also by my journalism which has run concurrently alongside my independent analysis. However, with a decade of energy transition already behind us, and a proliferation of newsletters and other media properties many of which cover climate, it’s time to consider a more thematic name. We live in a time where inaccurate optimism and inaccurate pessimism tend to surround the climate discourse. The Gregor Letter wants to target that problem more concertedly, not merely for the sake of accuracy, but because the next few years are likely to see an intensification of both optimism and pessimism as fossil fuel demand peaks, but stubbornly hangs on, making emissions declines challenging. Eventually, as we all know, emissions will indeed decline. But we may have to wait until the end of the decade for that outcome to be clear, and in the meantime, there’s a need to remain sober.

The IEA in Paris is suggesting that global emissions are set to peak in 2025 and then decline. The Gregor Letter strongly disagrees with this view. At best, if global emissions do peak in 2025, any decline in the several years following would be so slight as to be indistinguishable from a plateau. Again, this is precisely the kind of optimism that demands pushback.

It’s not even necessary to marshal charts to rebut the IEA’s 2025 view. For emissions to decline globally you need all three fossil fuels to enter demand decline. Let’s go through all three:

• Natural Gas. While the EU has probably just achieved a structural lowering of natural gas consumption, and will continue to work on that problem with heat pumps, clean energy deployment, and other efficiency programs, Europe at best consumes 10% of global natural gas globally. Meanwhile, we know that natural gas is already the partner to the wind and solar buildout as natgas turbines become ever more sophisticated, and can calibrate gaps in powergrids far more effectively than coal. The Gregor Letter has spent oodles of time this year discussing the natural gas problem and nothing has changed at all, in those prospects. While the IEA has predicted a three year slowdown in natural gas growth, it’s important to realize that natgas consumption keeps surprising to the upside everywhere.

• Oil and petroleum products. The Gregor Letter is resolute that global oil consumption peaked in 2019 at 100.6 million barrels a day, and will hover for 4-5 more years on a plateau that oscillates 1-1.5 percent around that level. This is great news! We can be encouraged about the myriad forces that have come together to create this peak. But a plateau of oil consumption does not contribute at all, even a little, to a decline in total global emissions.

• Coal. Well, who remembers when coal peaked in 2013, then fell gently for over seven years, only to storm back to those highs the past 1-2 years? The OECD massacred coal capacity last decade both in the US and in Europe. Shrug. Thermal coal has an industrial cousin in metallurgical coal, and energy transition is going to need lots of steel. The Gregor Letter sees no prospect however that coal consumption is going to start making higher highs, though. Nope. The problem is that the prospects for decline remain weak.

Now let’s look at the key chart from the just released IEA Net Zero report and the language they use to describe the peak they see coming, around mid-decade (2025). Note that the bottom chart is titled “Figure 1.3” and the acronym “STEPS” refers to a forecast under “stated policies.” In other words, no further policy action is required to achieve the below outcome beyond strict adherence to current policies, and trajectories. As long as the world follows current polices, the IEA sees a peak of emissions in 2025 and a fairly steep decline over the following five years to 2030, as indicated by the thicker green/aqua-blue line “STEPS 2023.”

Global energy sector emissions were 37 gigatonnes (Gt) in 2022 – a record high and a 5% increase from 2015. Nonetheless, progress since the 2015 Paris Agreement means that the outlook in the STEPS sees emissions peak by the middle of this decade and fall to around 35 Gt by 2030, which is well below the level of around 43 Gt projected in the Pre-Paris Baseline Scenario (Figure 1.3). To put this in perspective, this 7.5 Gt difference is equal to the current combined energy sector emissions of the United States and European Union.

Notice the baseline effects, dear reader. The decline the IEA sees by 2030 rests upon, and is dependent upon, emissions going higher first. By the end of the decade, however, emissions are just 2 gigatonnes below last year. Notice also that the IEA wants to highlight a kind of phantom victory, simply because its projection of 35 gigatonnes in the year 2035 is well below the 43 gigatonnes originally projected in Pre-Paris scenarios. On one hand, that is moderately useful to know. On the other, it’s overly complicating a subject that many people routinely find hard to understand.

It’s also worth pointing out that 35 gigatonnes is the level not just seen last in 2015, but in 2020 when the entire world was turned upside down economically—a world, by the way, which had already added quite alot of EV and wind and solar. It’s not confidence inspiring that the 2035 forecast has global emissions touching back to levels last seen during the pandemic, because frankly, even with tons of clean energy growth between now and then, that emissions low of 2020 will not be easy to replicate just 6 years from now! The world of 2020 is a world in which emissions from global transportation collapsed.

Suggestion: Let’s say global emissions do decline from 2025, and reach not 35 but 36 gigatonnes in 2030. Are we going to call that a decline? How will we know its difference from a yearly variation in an ongoing plateau? Answer: we won’t.

The IEA’s Net Zero analysis does not sufficiently back up its call for peak emissions in the remainder of the report. We are seeing this more regularly now: there is inadequate quantification of claims, as many writers and analytical teams justifiably tout the amazing progress of decarbonization, but say too little about total system demand growth. The Gregor Letter laid out this problem in The Big Number. If your forecasts for combined wind and solar growth don’t included total system electricity growth, then you have not really made a useful forecast in terms of emissions, and fossil fuel peaks, and declines. Just on that topic: The Gregor Letter has show multiple times that even if global wind and solar growth keeps pressing forward on its wildly rocket-like path, it’s not clear than any fossil fuel declines will occur in global electricity until just after 2030!

Overall, the IEA report’s claim to a peak of emissions in 2025 is both shaky, and not nearly as aggressive or momentous as it sounds. It requires that emissions go higher first, towards 38 gigatonnes, and then projects a very brisk decline to 35 gigatonnes five years later, a 5% decline compared to 2022.

The Gregor Letter remains firm in its conviction that the world is going to be rudely surprised during the 2025-2030 period when we see how plodding, slow, and minor are any emissions declines that arrive. That they arrive at all in this window is unlikely.

—Gregor Macdonald