The US will lead an initiative to triple global nuclear power capacity by the year 2050. If you understand the time factor crucial to decarbonizing global electricity, you will immediately understand the importance of this good news. If, however, you only have your eye on the wonderful and spectacular growth of wind, solar, and storage, you are more likely to wonder: why bother? Well, to see this problem more clearly it’s important to avoid thinking of this as a contest, pitting nuclear power vs renewable power. Rather, it’s far more crucial to attend to the main problem: when will emissions from global power start to actually decline? And how can we bring those declines forward sooner?

The Gregor Letter has previously offered up a simple model showing a plausible answer to this question: assuming continued spectacular growth of wind, solar, and storage, global emissions from electricity will not even begin to decline until 2030 or so—and the declines that come thereafter may only be slight. Why? Because of the central problem: total global demand for electricity is set to grow strongly as the world transitions myriad industrial processes from transportation to heating over to the powergrid.

Let’s first take a look at the wonderful growth of solar and wind generation. In the chart, combined wind and solar growth is projected to grow by the strong 16.6% compound annual growth rate observed over the past five years. In such a scenario, global power from wind and solar triples in just seven years to 2030, growing over 8,200 TWh. How awesome is that!

How could this soaring supply of clean electricity not send global powergrid emissions into rapid decline? Well, total system demand has been growing far more slowly than wind and solar, around 2.7% year. But it’s doing so from a much larger base. This is the classic problem of a small object growing at a high rate trying to catch up to a very large object, growing at a slow rate. Yes indeed the small, fast growing object eventually gets there. But the waiting is hardest part.

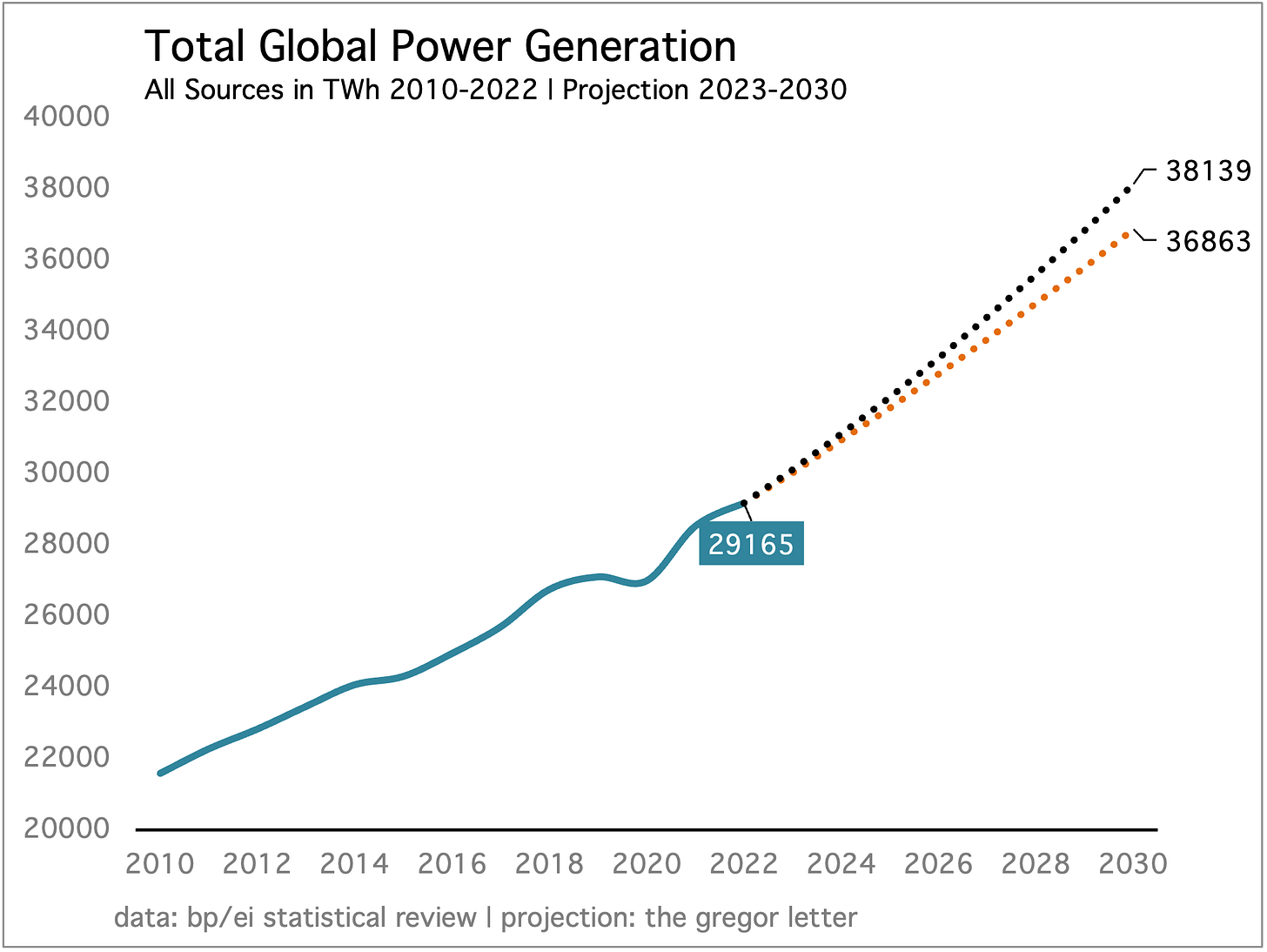

In the next chart, total global energy generation from all sources is plotted in two projection scenarios: 3.0% growth and 3.25% growth, through the year 2030. At 3.0% growth, total demand advances nearly 7700 TWh. In the second scenario at 3.25% growth, total demand advances by 8975 TWh. But remember, wind and solar generation is projected to grow by 8200 TWh. At 3.0% system growth, therefore, wind and solar finally cover that growth and begin to eat into existing fossil fuels in power. But at 3.25% growth, wind and solar—the small fast moving object—still has not caught up.

On our current course therefore, without new nuclear, we are asking too much of wind, solar, and storage. And we are going to be greeted in the 2030’s with a familiar, frustrating scene: emissions from global power either flatlining, or falling very slowly. Just a small, steady amount of new nuclear globally—even if it takes to 2030-2033 to start bringing it on—would amplify the undisputed leadership of wind and solar, and profoundly change these trajectories.

The Gregor Letter has been staunchly bullish on wind and solar since inception, and your faithful correspondent has been writing about solar’s potential for fifteen years. See for example this short essay written for The Economist magazine back in 2013, Pragmatic Solar, (opens to PDF, see page 6). So, if you are new to the letter, please understand you will find few venues more exuberant and friendly towards clean electricity growth.

But the time for sobriety is at hand. If you really detest nuclear, there are numerous counter arguments that one could make. You could argue that support for wind and solar could come instead through rapid deployment of geothermal power. You could argue that we can do much more to reduce total system demand growth (getting that rate back below 3.0%). Or, you could argue that we can build wind and solar even faster, at a rate that would start to look like an emergency rate, that one sees more typically in wartime. All those views are worth consideration.

As the US unveils the nuclear initiative later this month at COP 28, in Dubai, it would be encouraging to see presenters draw a similar framework, pointing out that the present trajectory just isn’t sufficient. If not new nuclear, then wartime wind and solar, for example. The worst outcome would of course see a nuclear initiative announced, but not met, as the years will roll onward. That’s why one of the key developments to watch next month is whether the World Bank can be persuaded to change its policy, and subsequently restart financing for new nuclear.

—Gregor Macdonald