Time to Grow

Monday 28 June 2021

The Federal Reserve has deftly managed the pivot in the US economy, which is now poised to transition from a complex reopening phase to normal growth. In the future, we will probably come to regard the June Fed meeting as a dividing line between the two parts of the post pandemic story. Fed Chair Powell, and the rest of the board, pinched off just enough of the mounting inflation worry in the future to retain the bulk of the current, accommodative-policy optimism. By doing so, the hand-off to normal growth will most likely smooth out price volatility in goods and services. All that’s needed now is a long-overdue infrastructure package to keep the global trade wheel spinning. Remember, the quicker the economy restores normal throughput, the quicker it activates all the myriad efficiencies which tamp down inflationary pressure.

Waiting for us on the other side of such growth however are the forces that have guided the world for twenty years now to a long-term, deflationary regime. Automation, technology, outsourcing, and a large supply of labor are all factors pressing downward on prices. They rested, but did not sleep during the pandemic. Now add to this mix the profoundly deflationary trajectory of decarbonization, a process which removes nearly half the lost capital spent on energy in the form of waste heat. If the world can manage it, these twin thrusts—pro-growth fiscal policies that invest in GDP-enhancing infrastructure, and, relentless downward pressure on inflation from technology and new energy—could potentially deliver a kind of goldilocks situation, or perhaps even a deflationary boom.

June, and therefore the first half of 2021, comes to a close on a justifiably optimistic note. The Federal Reserve has (mostly, with a couple of exceptions) resisted the siren call of the inflationary voices and stuck to its goals. A bi-partisan infrastructure bill, even if it’s for show, will likely pass and then be followed by a Biden administration led extender that adds substantially to those very same plans. Extremes in lumber, used car prices, industrial metals, and other goods and services are rolling over. Why, it’s almost as if a theoretical conversation conducted years ago, describing how a robust stimulus led recovery after a pandemic would roll out in sequence, is actually coming true. There is no structural shortage of lumber, copper, milk or meat that cannot be cured by the kinds of price signals delivered by the re-opening. The signals are clear: get back to work, get back to producing, get back to delivering, get back to shipping. If you simply had to buy a used car this Spring to take a new job, well, yes you probably paid a premium. But predicting that used car prices would eventually top out was a very easy call, among other easy calls.

Interest rates are telling us therefore that what lies ahead is normal growth. Rates have calmed down, and may drift a bit higher again. But not alot higher. To be sure, GDP growth rates will remain elevated for the current quarter, next quarter, and perhaps the final quarter also of 2021. But unemployment benefits are rolling off, the biggest part of the stimulus is behind us, and the V shape coming out of the March 2020 lows is mostly expired. That’s probably why financial markets entered a period of uncertainty between February and May: the forward path of growth, consumption, and policy was newly salient after a ferocious, nearly year long recovery in asset prices. With that three month period now behind us, financial markets are pretty clearly making their next move. But this time around, the rate of change will be far slower, and alot of the wildly speculative areas look primed for a period of slumber.

When you consider the speed at which the vaccines were developed and distributed, and the willingness of policy makers to go bigger and bolder than ever before, it raises the question of how risk is now distributed. In a number of previous periods, betting against human responses and human progress was a proposition with a decent reward. This time around, not so much. Technology and policy are real, and they have increasingly removed downsides to the human experience. That change in the equation appears to have irked some, a sign that old school, liquidationist impulses are still very much alive. But it must be said: letting everything “go to zero, to clean out the system” is just a dumb fantasy that imposes no costs on those who promote it, because they never have to suffer its realization. The deployment of robust policy to cancel human pain and suffering is a good thing, and carries far less “moral hazard” than many claim. Put another way, F.D.R. was correct, and his critics were wrong. His aggressive, anti-deflationary strategies were the precursor to today’s deeper understanding among economists, and the recommendations they make to standing governments. And F.D.R. is still correct, and his critics are still wrong. We must hope that populations understand this in the future too, as they did in the 1930’s, and as they did in 2020.

The US Department of Energy launched the hydrogen portion of its Earthshot initiative. The time to start paying attention to hydrogen is now. Simply put, if the cost to produce green hydrogen (sourced by wind, solar, nuclear, or hydro) falls over time, then a number of sectors that are harder to decarbonize will begin to adopt this resource. The DOE effort arrives at a moment when a flurry of hydrogen related activity is already in play, globally. The European auto sector is moving into position, for example, to drive demand for green steel. The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are looking to decarbonize their operations with hydrogen fueled trucks and other hydrogen powered equipment; and the LA Region more broadly is adopting goals set by the Green Hydrogen Coalition. From a market perspective, EU carbon credits are nearing a price that would make green hydrogen adoption feasible, economically.

The sticking point in hydrogen economics mostly centers around the cost of electrolysis. While electrolyzer prices have already started coming down, the learning rate will most surely need a boost from government policy. And that’s where the DOE comes in. Most are probably not aware that electrolyzer capacity in the US is growing quickly. (opens to PDF, and screenshot below).

In the same way the federal government helped kickstart wind and solar, something similar will likely unfold for electrolysis. Generally speaking, bringing supply into close geographical proximity to demand will be a crucial piece in kicking off cost declines, and that happens to be a central focus right now of the DOE effort.

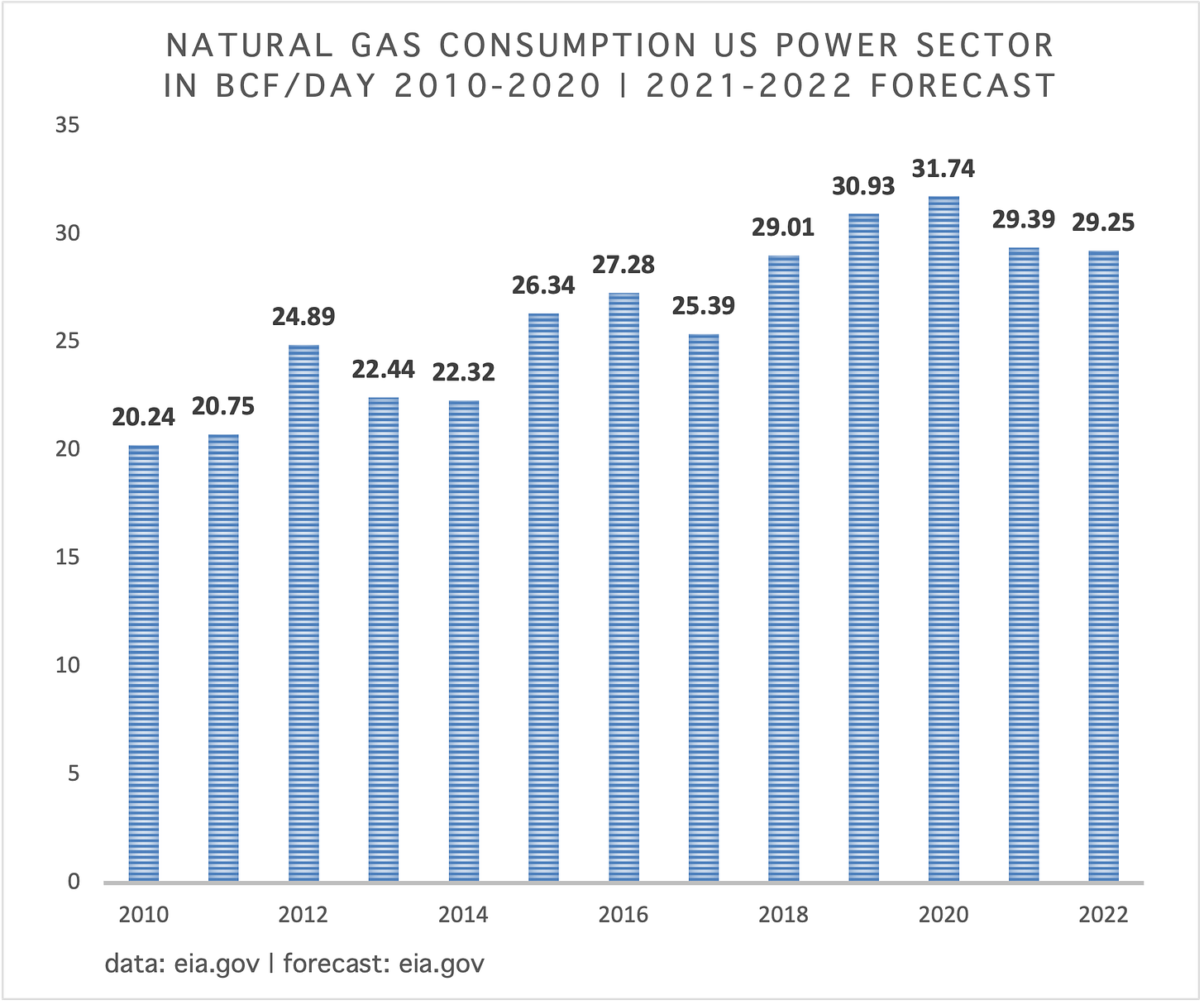

Trend growth for natural gas consumption in US power generation may be about to break. The forecast comes from the EIA, which reported in its latest STEO that demand will not grow in either 2021, or 2022. That would be the first back-to-back year of no growth since 2013-2014. The forecast comes at a time when the majority of capacity additions to the US power sector are due to wind, solar, and battery storage. Talk of peak gas has been around for a while, of course. And there’s no indication yet, not even a little, that global natural gas consumption has peaked. But peak demand in sub-sectors like US power is imminent now that ultra-cheap wind and solar are finally being joined by falling costs in storage.

The United States’s energy balance sheet is in rude health as the country’s net dependency on imported energy continues to fall. Energy independence is a tricky concept and frankly, not especially important. The obsession with the idea is largely an outgrowth of the oil embargoes and related crises forty years ago. There’s nothing wrong with a global trade in energy, which arises from the inevitable fact that most countries are in surplus of some energy sources, and in deficit of others. The US is still a net importer of crude oil, for example. But it is not an extreme importer. The pejorative version of dependency should be reserved for more extreme imbalances.

But there’s a balance sheet perspective to a country’s import and export profile to be considered, and in the case of the US, its balance sheet is looking great. Simply put, the US produces oil, coal, natural gas, nuclear, wind, solar and hydro—and in some of these it has surpluses that it exports, like natural gas, and in others deficits where it must import, like oil. The mighty ascent of domestic renewables, for example, has eased the call on natural gas, freeing up more for export. And the ascent of US oil production has had similar effects, especially when considering the US’ vast petrochemical complex that now exports large volumes of petroleum products.

When you sum all these parts you solve for net import dependency. And in the chart below, you can see that at one point over 15 years ago, net imported energy as a percentage of total energy use stood at 30%. But starting in 2019, that figure actually went negative after a long decline. The US is using less energy, exporting more energy, and creating its own energy to the following result: it’s no longer dependent, on a net basis. And that’s healthy from a trade balance and financial view.

Projected earnings for the SP500 now stand at $213.07, an astonishing recovery in just the last six months. At least as impressive is that 2021 analyst consensus earnings, at $190.56, are far above the 2019 level of $162.97. As recently as late last year, the idea that 2021 would even match 2019 was still uncertain. The data comes via Ed Yardeni and just to note, the forecasts may have changed again (to the upside) by the time you click the link. (opens to PDF).

Elevated demand increases supply, a dead simple proposition we keep forgetting. This is the argument, or perhaps the reminder, from Mike Konczal and J.W. Mason in their New York Times Op-Ed, How to Have a Roaring 2020’s (Without Wild Inflation).

A boom, defined more precisely, is more than just faster growth: It’s an extended period when spending pushes against the productive potential of the economy, which creates pressure on employers to increase wage gains and make capacity-boosting investments. An economy in such a healthy state feels like an unfamiliar, even uncomfortable, idea to many Americans because now we rarely experience it.

Many economic observers seem to have not fully absorbed the fact that the world has been building modern distribution channels for over 100 years. While some constraints are quite real and will not resolve quickly—like semiconductors, owing to the space-program-like engineering required to mount additional capacity—most of the world’s products and services scale pretty easily.

But scaling the production of newly required products often requires governments to kick-start capacity. That view is explained nicely in Dan Alpert’s most recent New York Times Op-Ed, The Side of Wall Street That Matters Most Is Begging for Infrastructure.

If the U.S. government is to compete with countries that have already helped create modern infrastructure markets domestically, its procurement commitment must extend long enough to galvanize large-scale private-sector capital investment in plants and equipment. This underappreciated power of federal procurement — of the public’s ability to kick-start innovative markets by itself — may be the most accessible way to reverse the corrosion of our manufacturing base and restore the well-compensated, middle-class jobs Mr. Biden pledged to bring back.

The flurry of proposals that’s arisen over the past year to attack US capacity deficits in medical equipment and now batteries, semiconductors, and solar panels is the signal that the economy is once again transitioning to new needs. And having at least some domestic capability in these areas is wise.

A brutal heatwave landed in the Pacific Northwest this weekend. Multiple records will surely have fallen by the time it dissipates. What’s particularly bracing about this extreme heat event is that it’s arriving in June. Normally, in the back half of summer, it is not unusual for Portland to see consistent daytime highs in the 90’s (F). But it is also typical for Portland to cool off quickly at night: the region behaves as a dry Mediterranean climate in summer. Without so little humidity, heat lifts effectively after sundown. But there’s no chance of that happening this time around, with temperatures forecasted to hit levels from 110-115 F.

On Saturday, a new all time maximum temperature record of 108 F was set for Oregon:

Another factor to bear in mind is that, despite popular perceptions, the Pacific Northwest actually receives less annual rainfall than many US cities on the east coast. Distributed over a more continuous length of time from October through April, the rainfall protects the region from burning in summer when the dry, rainless period begins. Chronic mist and drizzle periods are stitched together to hit those annual rainfall marks, therefore. Without them, Portland and Seattle would be far more vulnerable to summertime fires that reach deep into settled areas, the kind that have historically broken out in Los Angeles, for example. The current heatwave will surely erode that protection, lowering water content across the region. With the mega-drought clearly underway, Portland and Seattle will head into July and August in a potentially dangerous condition.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title is available and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.