Trade Games

Monday 10 November 2025

The tariff case currently before the Supreme Court of the United States is quite significant, as its resolution will go a long way in determining the extent of presidential power. The conservative movement in the U.S. has largely tended toward executive power expansion in recent decades, and were the case decided in favor of the president, it would inarguably mean a true step change had occurred not just in the growth of executive branch power, but in the separation and balance of powers that defines the relationships between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

When initial oral arguments were made this week in Learning Resources v. Trump, we learned fairly quickly that the current justices of the Supreme Court—and especially the conservative judges—were simply not willing to go that far. Chief Justice Roberts and associate justices Barrett and Gorsuch were notably skeptical if not slightly alarmed by the arguments being made by the government’s lawyer, John Sauer, the current solicitor general. The core issue at hand: If, in a 1977 piece of legislation called the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, Congress gave the president the right to erect an across-the-board tariff scheme with the rest of the world, then why doesn’t that legislation refer anywhere to the right to establish tariffs specifically? This matters quite a lot, because tariffs actually raise revenue, and that is always and everywhere the purview of the legislative branch. And perhaps just as important: If Congress did grant such broad rights, would that not awaken the major questions doctrine? This legal principle holds that Congress cannot transfer policy-making to the executive branch in matters that greatly affect the political and economic realm.

When President Trump imposed across-the-board tariffs on the entire world this past April, he arrogated powers to himself and the executive branch that no president before him has attempted to claim. Justice Barrett pressed the solicitor general fairly hard on the fact that the powers enumerated in the IEEPA legislation not only do not include the word tariff, but “the actual verbs” cited in IEEPA—investigate, block, nullify, void, prevent, prohibit, regulate, direct, and compel—have not been used elsewhere by Congress as stand-ins or substitute concepts for tariffs. Chief Justice Roberts appeared quite resolute in his questioning, saying several times that tariffs are indeed taxes—a theme also sounded out by Justice Sotomayor. Gorsuch, meanwhile, appeared to be rather agitated by the top-down implications of the case, as he repeatedly laid out a scenario whereby either Congress and/or the Supreme Court hands too much power to the president. The country would discover over time, in his view, that such power, once granted can never be clawed back. By the time the plaintiff’s lawyer, Neal Katyal, rose to make their case, it was already clear the government was facing a steep climb: IEEPA does not grant tariff powers in the text, and even if it did, granting revenue-raising powers to the president is something Congress simply can’t be allowed to do. Indeed, it was Justice Thomas who asked the first question of the day to the U.S. solicitor general: “Could you spend a few minutes explaining why the major questions doctrine is not applicable here?”

Prediction markets also lurched hard on the outcome. Kalshi published a dedicated story on the days proceedings: Trump tariff odds collapse during Supreme Court showdown. Many, of course, want to know when the case will be decided, and also whether Trump can rebuild his tariff scheme should the court strike it down. Well, the court has until June of 2026 to decide, but experts note that they took this case on an expedited basis, and justices actually acknowledged this fact during oral arguments, indicating that they understand both the scope and the urgency to make a decision. A decision could come sooner. As for Trump’s recourse, there are reasons the administration didn’t go with plan B in the first place: because trying to rebuild the current scheme will be much harder if they have to go back and rely on other tariff provisions—which are narrower in scope, and some of which are already in place, on countries like China.

Further reading:

Ricardo in Reverse, April 14, 2025 from Cold Eye Earth.

In tariff cases, verbs rather than major pronouncements about presidential power give the court the off-ramp it’s looking for, November 7, from Scotus Blog.

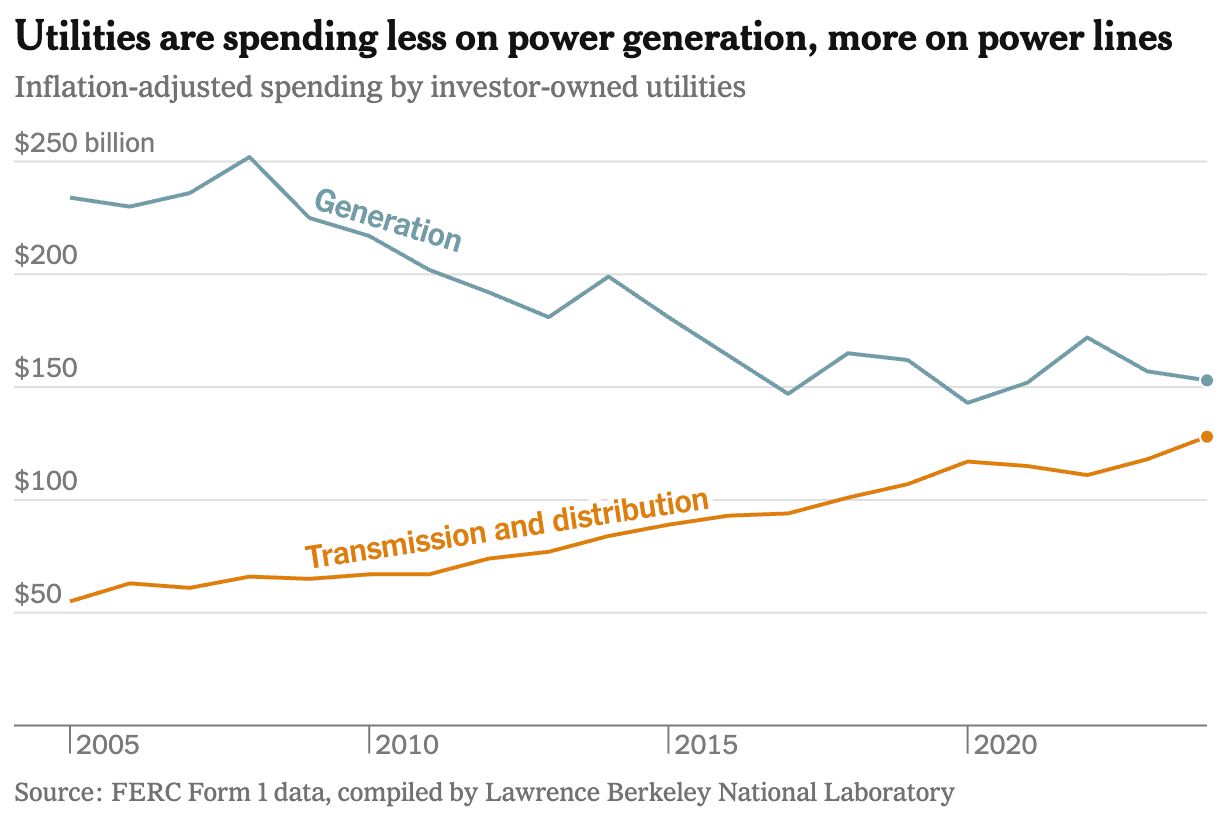

While hard to quantify, a reversal of the current tariff scheme would be enormously beneficial to myriad small businesses that rely on imports, and more broadly to the manufacturing and housing sectors. The main plaintiff in the tariff case is a classic example: a children’s educational toy company that pairs instructional approaches with simple items imported from abroad. Not only would U.S. businesses receive refunds, but the air would finally clear on the trade outlook. Of particular concern to readers of Cold Eye Earth, of course, is the entire power sector—a capital-intensive industry that produces cutting-edge energy technology, and which relies on raw material imports. As most current reporting shows, it’s not the cost of power but rather all the associated infrastructure that’s driving inflation in electricity prices. A graph from the linked New York Times article:

Cold Eye Earth remains quite resolute in the top-down, macro view that if you want to tackle climate change, then it is axiomatic that you must be supportive of free trade. Tariffs are bad; they raise the cost of mitigation unnecessarily, and they slow the speed of transition. If climate change is an existential threat, with the potential to radically shift societal cost levels higher and higher (uninsurable homes are merely one example), then how can one possibly care if China is making all the heat pumps, solar panels, and transmission wires?

The Economist is reporting that China now makes more money selling energy technology to the rest of the world than the U.S. makes selling oil, petroleum products and LNG through its energy exports channel. This claim is a bit sloppy, because there’s a big difference between gross revenues and profits, and here one has to conclude The Economist is talking about revenues when it writes:

China is now making more money from exporting green technology than America makes from exporting fossil fuels. This trend will continue simply because renewables are cheap; if you doubt the appeal, count the solar panels on Pakistani roofs. The work China does on cutting emissions at home—ever cheaper renewables, more abundant storage which makes those renewables more useful, better electricity markets, long transmission lines and all sorts of associated expertise—will thus be increasingly relevant, and sellable, beyond its borders.

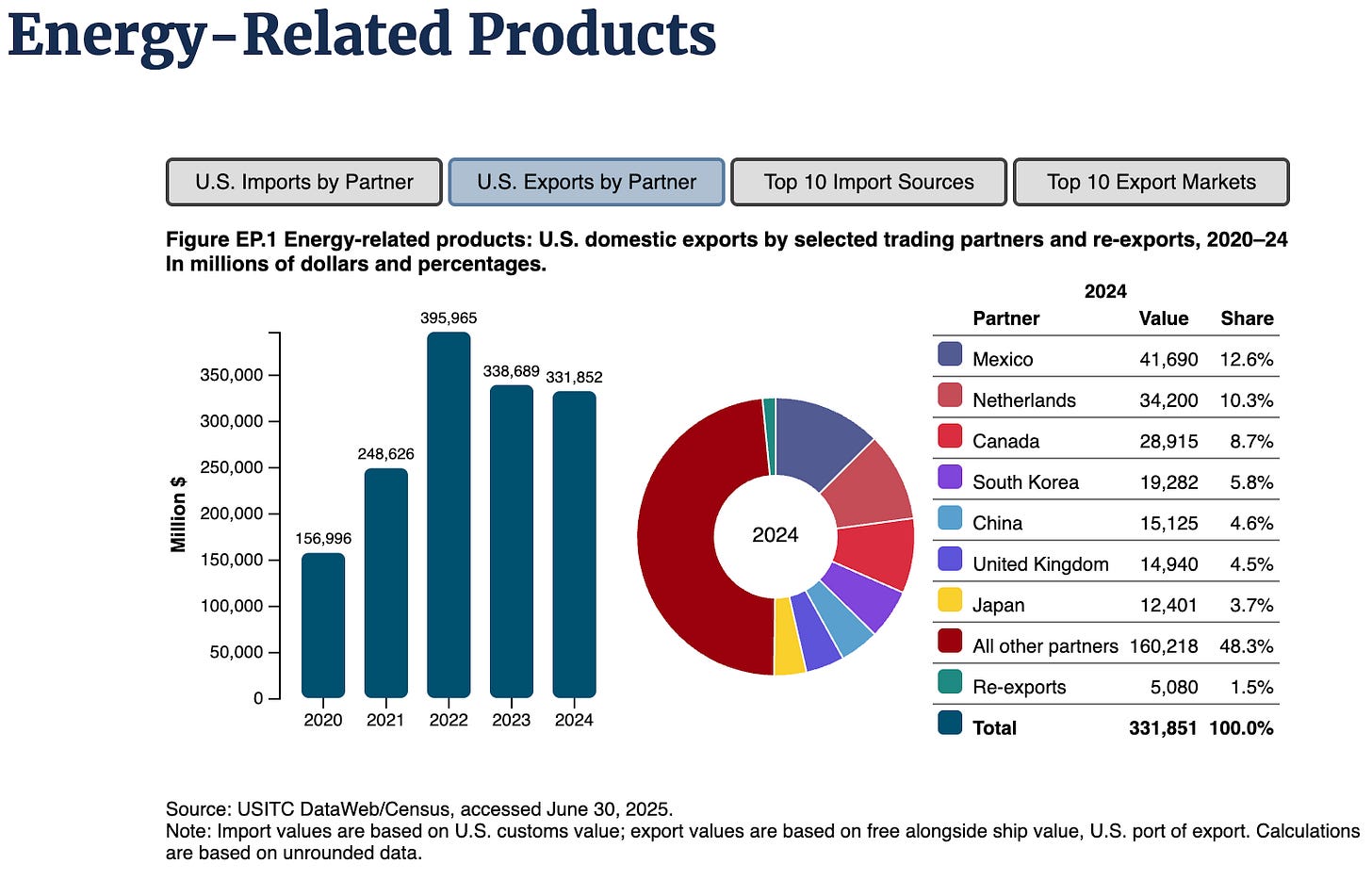

While we don’t possess the tools to gauge profit, we can at least take a peek at the U.S. data. Just to say, the U.S. actively exports energy-related products like wind and gas turbines, power equipment, and other electrical equipment and components—but of course its sales of oil, coal, nat gas in LNG form, and petroleum products lead the category. According to the U.S. International Trade Commission, energy and energy-related product exports totaled $331.8 billion in 2024, and that gross figure is probably the best “comp” to the export category The Economist invokes for China. Here is the table from the ITC, and note the spike that occurred in 2022, which is not hard to understand: That was the year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which lifted the prices of all energy from coal to LNG to petroleum products.

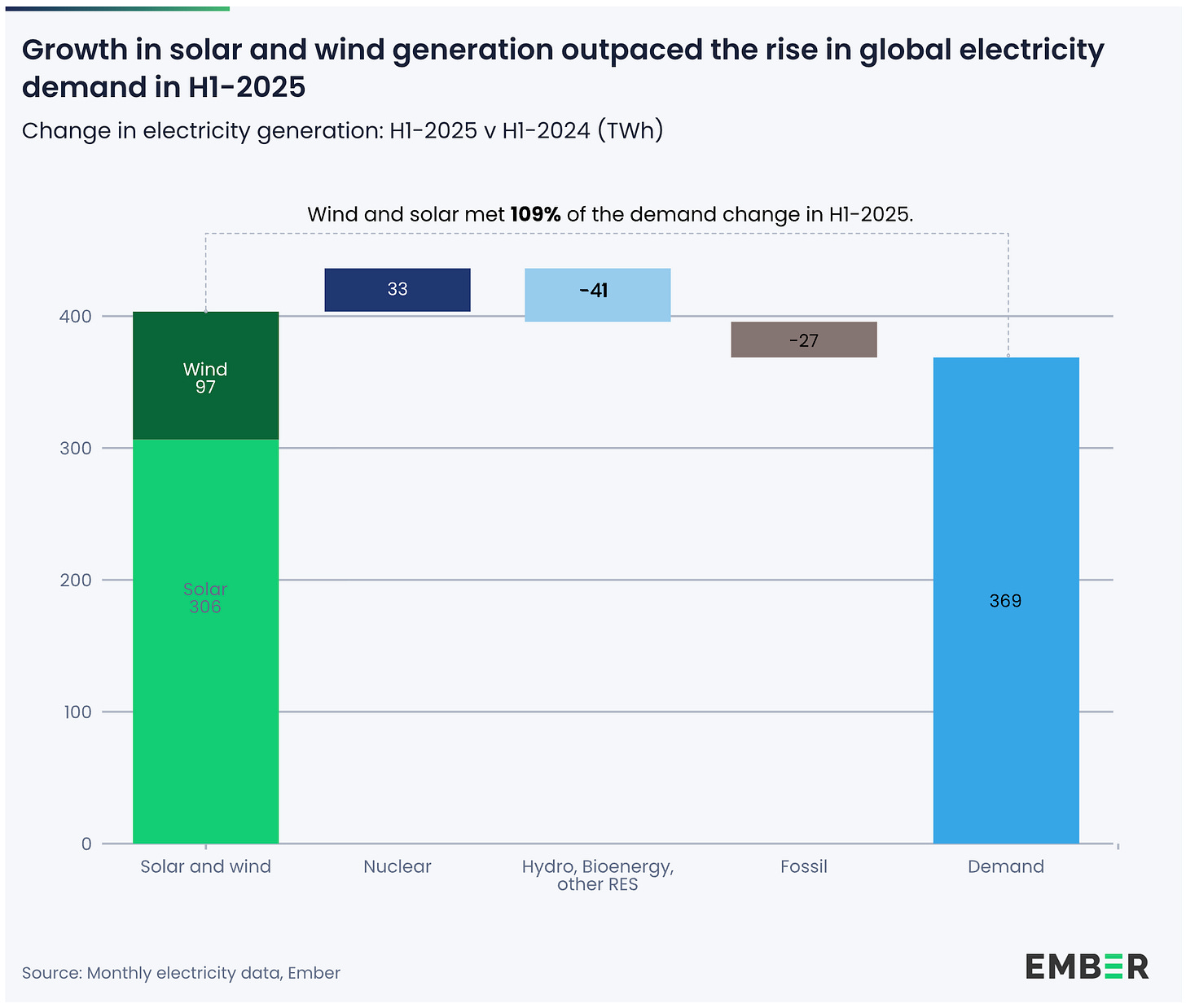

Midyear reporting indicates that the global power sector is doing a good job covering marginal growth with wind and solar. That is excellent news, though it’s also the expectation. The mantra here at Cold Eye Earth remains that wind and solar will, bit by bit, domain by domain, cover marginal growth of power and then eventually will cover—consistently, and not occasionally—marginal growth in power at the global level. According to Ember, that’s exactly how the first half of 2025 unfolded.

The important detail, however, can be found in the figure that matters most: total global power demand growth, which according to Ember grew only 2.6%. Readers will recall that we are supposedly in the middle of a three-year run of above-trend power demand growth, which the IEA sees running hot at around 4.0% per year through next year and into 2027. If the data estimates are correct, 2.6% as applied to the global level of power demand is quite meaningfully below that forecast, and thus makes the wind and solar capability achievable. At 4.0% growth, well, not so much. What’s really helpful here is that it drives home the fact that renewables growth is subordinate in importance to total power system growth. You have to care about both figures, you have to track both, and always remember to highlight them both, as a pair.

Here is Ember’s graph, showing that total power demand grew by 369 TWh, and how that demand growth was nicely covered by the growth of wind (97 TWh) and solar (306 TWh), which totaled 403 TWh.

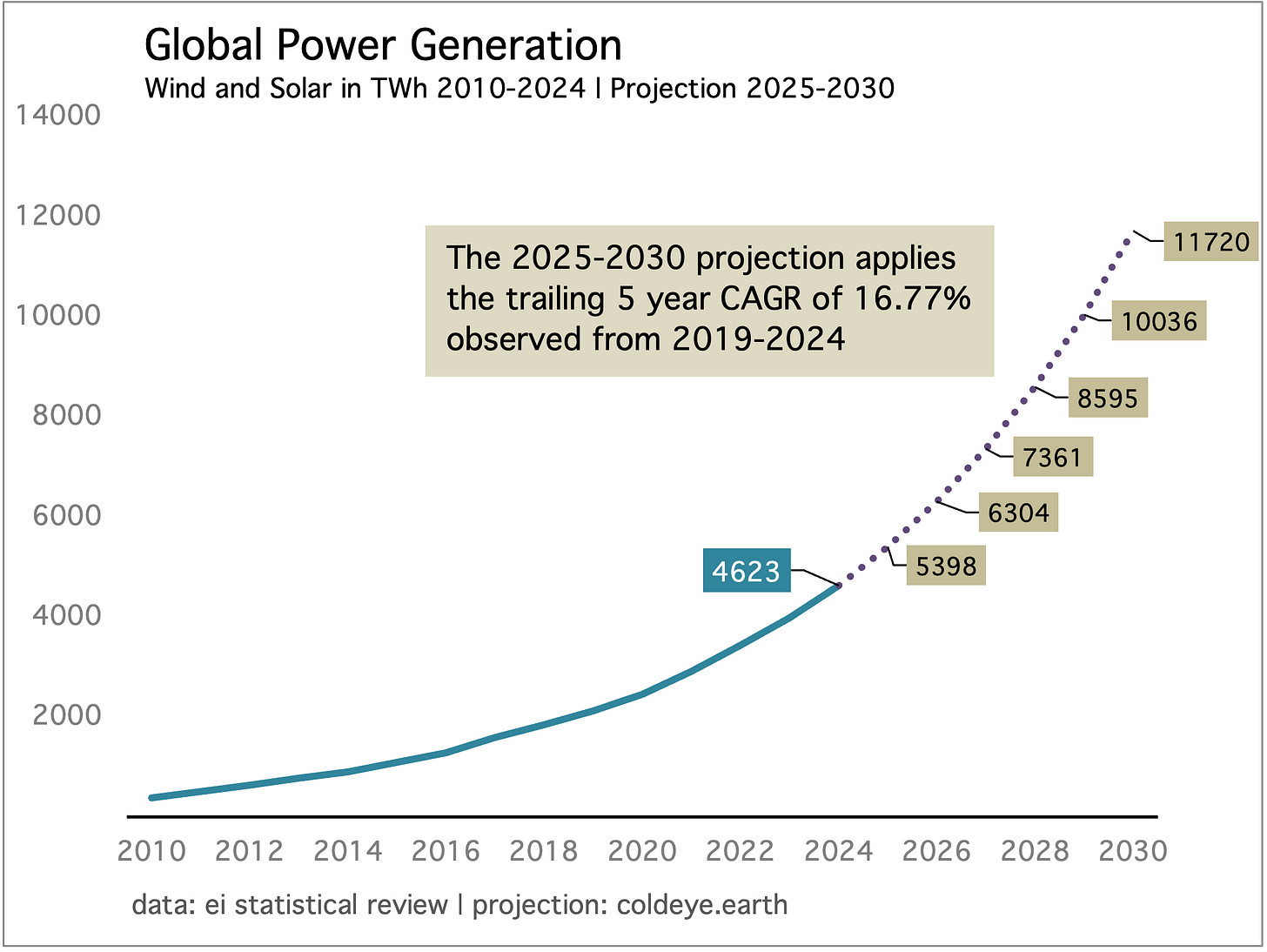

How does the first-half (1H) performance of wind and solar generation growth compare with the forecasts? Readers will recall that Cold Eye Earth uses a very simple trailing five-year growth average rate to make single-year outlooks. No complex modeling, no tweaks or adjustments, no inputs from news or experts. The method is indeed almost moronically simple, and yet it has been working extremely well!

The most recent update to this forecasting method occurred earlier this summer when the full-year 2024 data was released in the EI Statistical Review. The Cold Eye Earth projection indicated that combined generation from wind and solar would advance by 775 TWh in 2025, moving from 4,623 total TWh in 2024 to 5,398 TWh.

Now let’s return to the Ember estimate of wind and solar generation growth for just the first half of 2025: 403 TWh. What is half the Cold Eye Earth projection? That would be 387.5 TWh. That’s within 4% of the current estimate. Magic!

To take some credit, the choice of the five-year trailing rate has some thought behind it. The five-year period appears to strike the right balance between a ten-year rate, which is probably stale, and a shorter one- to three year rate, which might be unduly influenced by an outlier year. For those who want to do this at home, the DIY method is simple.

Determine the trailing five-year compound annual growth rate of combined wind and solar generation, using the EI Statistical Review data-set.

Apply that rate to the following year, and no further, for a one-year forecast.

• • •

Speaking of DIY, your faithful correspondent has, over the years, custom fit winter fenders to a number of bikes. Bike riders will appreciate the tangled web of frustration involved, which eventually resolves into a pair of fenders that look good, and don’t rub. Years later, having proven these capabilities, it was a pleasure this year to not just buy some new fenders, but to let the bike boys at the local shop undertake the task. :-)

The newsletter has a number of cyclists among the readership, and while you may have seen the Breadwinner B-Road before, there are new components to mention. Mainly, it’s an all new 2025 Shimano 105 mechanical groupset which works beautifully, and has better gearing for hill climbing. Not that it’s a goal, but a good portion of the bike is made in the U.S. The frame (Breadwinner) and fenders (Portland Design Works) are made right here in Portland, and the hubs are White Industries, from California. A note on the Shimano 105 groupset: it’s now the only mechanical set they make, as all the others have gone fully electronic (and there’s a 105 electronic too). Finally, look at the coverage offered by those low hanging flaps on the fenders! Let the winter cycling season begin.

• • •

• News briefs • Abigail Spanberger won the Virginia governor’s race in a landslide, bringing sweeping change also to the state’s House of Delegates. That portends good things for the state’s clean energy efforts. • EV sales reached 22% of passenger car sales globally last year, which is spurring the growth of charging stations worldwide. • The redistricting wars could net an extra 7 GOP seats in the House of Representatives, which is why the success of Gavin Newsom’s counter-effort this past week is a big deal. • Copper demand is expected to rise nearly 25% by the year 2035, according to Wood Mackenzie. • Simon Moores of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence says that battery energy storage systems (BESS) are increasing market share and have been growing so strongly that they now compose 20% of the global market. • An event in China which showcased a new humanoid robot whose walking motion was so smooth, the presenters had to cut it open to prove to the audience a real person was not hiding inside. •

—Gregor Macdonald