Transportation Talk

Monday 1 April 2024

The systemic problem that cars present to economies won’t be solved by a transition to electric vehicles. But make no mistake, the EV drivetrain does indeed solve both a severe emissions problem, and an energy inefficiency problem, endemic to the internal combustion engine. The recently popular foot-stomping about the natural resource needs to manufacture EV, therefore, can largely be dismissed as a case of whataboutery, or really, a failure to account for the natural resource needs to produce and run cars in the system as it currently exists.

And yet, this is true: the adoption of EV will not solve the aggregate spatial problem created by cars. Their domination has delivered losses to societies in how cities are designed, imposing large and ongoing costs through inefficiency, and an ever-rising maintenance burden to the state. In other words, organizing your transportation system to a point of extreme dependency on individual car ownership, rather than public transit, is one of the worst ideas ever. For example, while California has in recent years done an excellent job building out public rail transit in Los Angeles, the state is still locked in to the same transportation system that developed after WW2. In other words, highways and freeways. Transportation remains the second biggest state budget item, after health and human services, and at $33 billion is expected to account for at least 10% of the 2023-2024 budget of $310 billion. To put that into perspective, that’s equal to about 20% of the US Department of Transportation budget of $145 billion.

A 2015 research report produced in partnership with the London School of Economics, for example, estimated that sprawl—the self-populating, topographical mess that arises when cars are the preferred mode of transportation—may be costing the US economy as much as a 1$ trillion a year. Studies of this kind can of course come to a variety of conclusions, but a graph from that report (opens to PDF) is worth sharing, because its message is so stark: Atlanta produces 7 times the transport carbon emissions of Barcelona.

Another way to come at this question from a top-level view comes from academic disciplines that study growth itself, and the evolution of large systems as they grow and change over time. For example, in the early days Los Angeles much of the westside of L.A. and the San Fernando Valley were still sparsely populated as the city at that time was largely restricted to downtown, and the earliest developments like Pasadena. It’s quite understandable that with so much land to develop, L.A. embarked on a unique dream: the building of a new kind of city, one less composed of apartment blocks, but single family homes. At the time, with such a small population, that project was quite affordable to build, and cheap to run. But after you 10X that program several times the equations begin to change. The next step L.A. took was a fatal one: in trying to escape the looming morass of too many cars on surface streets, it overlaid a freeway system on top of the city hoping that would help. It did, for a while. And then that system too no longer solved the problem. It’s an old story.

Academics like Joseph Tainter investigate the development timeline of such systems, trying to identify the moment they go “upside down” as costs begin to press up against the benefits, and eventually overwhelm those benefits. Tainter’s views are summarized in his well known quote: Eventually, the point is reached when all the energy and resources available to a society are required just to maintain its existing level of complexity.

Have the road and highway systems of the world become nothing more than maintenance white elephants, costing economies more than any economic advantage they confer? That’s a fairly complex question to answer, but let’s offer one general idea. When goods are shipped into the Port of Los Angeles, for example, they are then redirected by both trains and trucks out of the LA Basin to many points beyond. This system is no doubt profitable, in part because containerization concentrates the economic value of shipped goods into their most optimized physical form. Even more to the point is that Los Angeles some years ago carved out a below-grade train corridor so that goods could flow uninterrupted out of the port—a kind of dedicated bus lane for trains.

The economics of the system change dramatically, however, when thousands of people run short errands in 7000 pound vehicles (or heavier) in the course of daily life in the rest of Los Angeles. Instead of a high-value single route, now we have thousands of low value routes, and society has to pay dearly for that supposed convenience—directly through taxation to maintain the street system under heavy usage and indirectly through pollution and emissions. Cities like London decided they’d pretty much had enough of this type of system, and starting in the year 2000 imposed a day charge on personal automobiles, and then got back to the business of building underground trains. Not so complicated, is it.

In a recent email sent to Cold Eye Earth, activist group Extinction Rebellion celebrated interrupting the International Auto Show in New York City with the following message: “No EVs on a Dead Planet.” The email then made several claims. First, that “Electric vehicles do not solve the fundamental problems with cars.” Well yes, that idea may not be widely understood, but we are learning the depth of this truth as the global highway system hangs on, and continues to expand. Your faithful correspondent began to make the same observation years ago.

The group’s second claim is not without merit, but is crafted to imply that EV are a possibly even worse than ICE cars, though it does stop just short of that claim:

The construction of electric vehicles is as carbon-intensive, if not more so, than that of conventional cars powered by fossil fuels. More important, cars themselves damage the climate in many ways above and beyond their gas consumption. Cars are constructed out of materials that are very difficult to produce. The excessive steel in cars is incredibly climate-unfriendly to produce. The many superfluous electronics in cars contain rare earth metals and require expensive, shipping-intensive manufacturing processes. The fact that cars are heavier and larger than they need to be means that all cars, including electric ones, are incompatible with a livable future.

Energy transition does have a problem in that it necessitates a new call on natural resources, in everything from steel to battery metals to the production of silicon. Indeed, wind and solar can be thought of as steel-in-the-ground infrastructure, and we need to build much more. But most cautionary alarms about a new call on resources conveniently ignore that colossal call on resources made by the current system—you know, the one that’s been running 24/7 for the past 250-300 years?

So activist groups need to beware of their propensity to default to hyperbole, because transitioning global transport to the electric drivetrain really does represent a huge downshift in emissions, and especially energy savings, as an EV requires at best just 40% of the energy to go one mile as an ICE, and in some case may only require as much as 30% of that energy. Switching vehicle drivetrains to electric in fact solves not one, but two major problems. First, it removes petroleum from the system. Second, by removing combustion from the level of the individual engine, and thus sourcing its energy from the powergrid, an EV performs a kind of miracle-flash of efficiency.

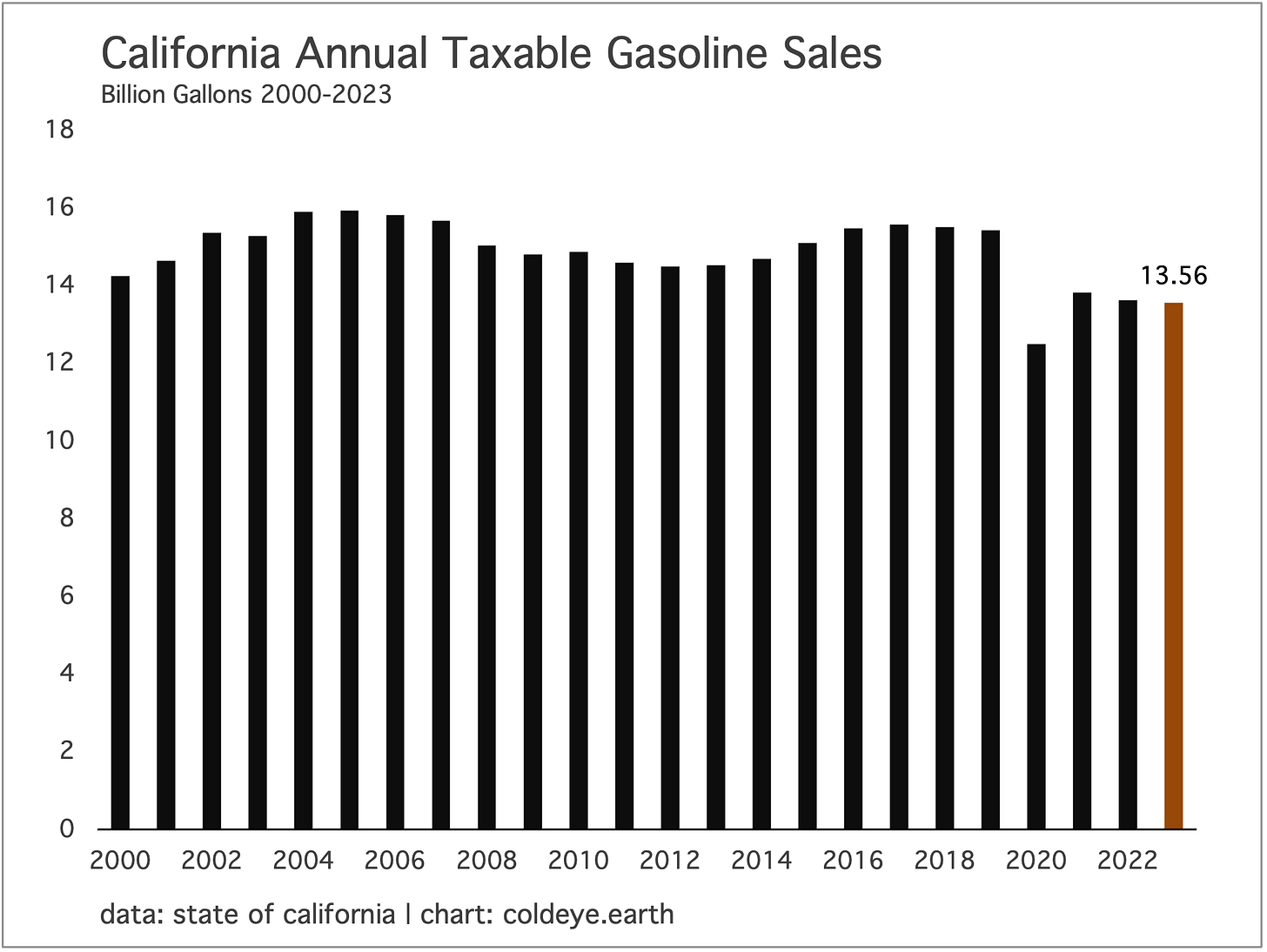

To illustrate, below is a chart showing that for a couple of decades now, California vehicles have consumed around 14-15 billion gallons of gasoline each year. Lately however, gasoline demand has not only failed to recover to that level since COVID, but it has actually started to fall, albeit very gently.

Now imagine all the current vehicles in California running on just 5-6 billion gallons of gasoline each year. Yes, that’s right. Because that would be the correct way to express the decline in energy equivalent terms of switching all ICE vehicles in the state to electric vehicles. The reason your average person stares in disbelief at stats like these is not because they doubt EV per se, but most people just have no knowledge of how much energy an individual combustion engine wastes. Now multiply that waste by 30 million vehicles, each running their own highly inefficient engine. EVs essentially allow us to centralize electricity production at individual power plants (increasingly wind, solar, and storage) thus obviating the catastrophic losses of executing combustion at the level of the engine.

If you want heat pumps, grid storage, high-voltage transmission, electric vehicles, green steel production, hydrogen production, the deployment of energy carriers like ammonia, and wind and solar, then you are going to have to dig up lots and lots of raw materials. The intrinsic difference however between the new system being born, and the existing system still in place, is that the new system will release far less energy to the atmosphere. That’s called a trade-off. And it’s a good one.

Emissions from the US transportation sector are headed back up, unsurprisingly, given that the country no longer has any policy in place that would lead to declines.

The power sector meanwhile continues to make excellent progress, despite the uptake of natural gas, because the coal crash is still rolling onward. Back in the transportation sector, however, emissions in 2023 came in at 1858 million tonnes, about where they were over twenty years ago. The chronic oscillation over that time is made through two main puzzle pieces: the US population and vehicle population grew, but nevertheless tailpipe emissions improved steadily. Note however this doesn’t actually achieve emissions declines. As Cold Eye Earth likes to point out, if you want emissions declines, you must both introduce newer, cleaner technologies while at the same time retiring the old. The uptake of EV at the current modest rate in the US simply won’t get the job done, until much later in time.

The 20th Century Limited broke travel time barriers in 1902 on the run from Grand Central Station in New York to LaSalle Street station in Chicago. Up until this point that trip took a full 24 hours. But the Limited smashed that time by 4 hours, and just three years later in 1905 had lopped off another 2 hours. By the late 1930’s however, with new train sets, the Limited brought the trip down to just 15 hours, with trains leaving New York at 6PM, and arriving in Chicago at 9AM the next morning.

We discuss these train times today because there’s a general sense that contemporary train travel in the US is so badly out of date that trips made a century ago were quicker than today. In the case of the 20th Century Limited, that’s true—but surprisingly, not especially so. Today’s facsimile is Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited, which does the New York-Chicago run in 18 hours and 32 minutes. And yes, that is the same route: From NYC directly north to Albany, then across the cities of upstate NY, then down Lake Erie to Cleveland, and onwards to Chicago.

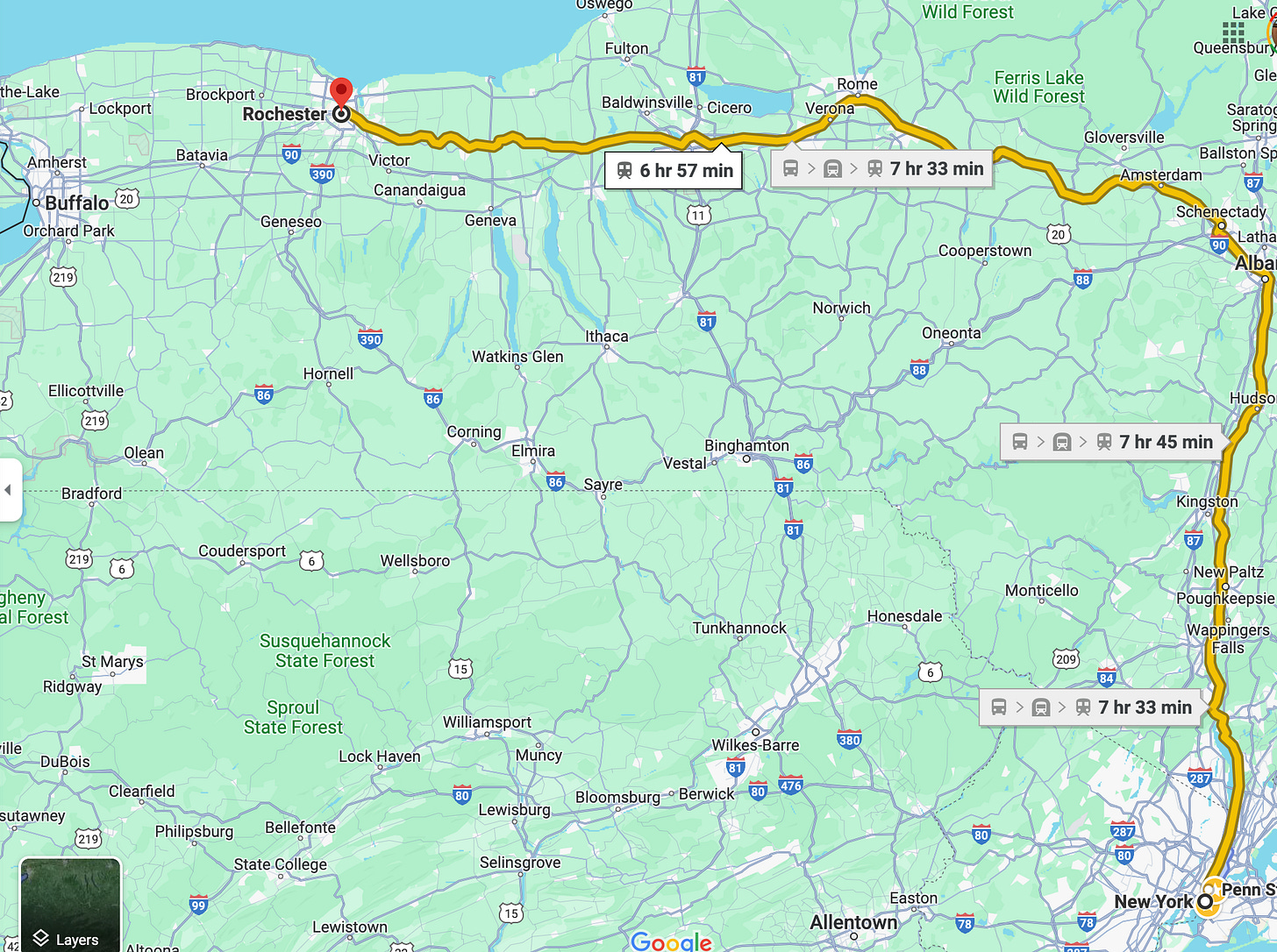

Your correspondent is thinking about these things as I head back out to the East Coast with my 17 year old, where we must choose a university to attend. Our trip will take us to Easton and Bethlehem, PA, then onward to Troy and Rochester, NY, then Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Washington, DC. We are particularly constructive on the University of Rochester for the way it combines both a named school of Engineering (Hajim) with solid academics, especially Economics, along with other choice programs, like the Institute of Optics. We are also aware that few college age students dream of attending school in dark, upstate NY where days of sunshine are few, and a snow machine runs 24/7 through the winter months.

The question I find myself asking: how much more attractive would the cities of upstate NY become, if they were served by a high-speed train to Buffalo, and then offered two routes to continue: one to Toronto, and the other to Chicago? (Yes, the Maple Leaf hits all the same cities in NY, after departing from Toronto). What if upstate NY cities were regarded as being in much closer proximity to Chicago, Toronto, and New York? Would that change not just perceptions, but the willingness of people to live and work in this region?

I think the answer is unequivocally yes: it would bring a significant change to those cities. Notably, all these cities contain universities, (SUNY Buffalo, University of Rochester and Rochester Institute of Technology, Hobart, Syracuse University, SUNY-Albany, and Rensselaer Polytechnic. One should probably include Colgate, Hamilton, and Skidmore too, among others) and we know from examples of urban revival that universities can have both an anchoring effect in terms of stability, and can also help bring about expansion.

The question becomes therefore, how much of a transformation? Well, that probably depends alot on the type of high-speed rail that could be achieved. Today’s trip, for example, between New York City and Rochester takes 7 hours on today’s version of The Limited, which has a top speed of 110 miles an hour, but clearly doesn’t sustain that speed on its journey. The current discourse in the US is that high-speed rail could be achieved at 125 miles an hour, with upgrades, but the rest of the world would justifiably laugh at that claim. 125 mph? That’s commuter-rail speed in parts of Europe and the UK. You won’t gain the attention of the public by chopping an hour off these trip times.

But what about true high speed rail? The distance by train between New York City and Rochester is about 375 miles. A well known high-speed route in Europe that’s comparable is the Madrid-Barcelona line, at 385 miles, which was designed for trains to travel at about 215 miles an hour. Travel time? Two hours and thirty minutes. At that speed, one could easily head to Toronto for the weekend or a business meeting, avoiding all the hassle of airports, with a trip time likely at 4 hours or less. Most of all, it would signal to every prospective worker and professional that taking a job in this region would not, in fact, be akin to exile in Siberia.

There’s a bigger, more important reason however to consider what this lack of investment may imply for the US. As you may know, New York State is one of the regions in the US readymade for expansion of semiconductor manufacturing. Why? Because many of the universities previously named, along with Cornell, are already getting into position to bolster research budgets and faculties on top of the CHIPS Act. If we zoom in on the US Semiconductor Ecosystem Map, for example, we find that Applied Materials already has a presence in Rochester, along with AMD.

What we are coming to see, therefore, is that woefully out of date transportation policies in the US are costing us money, and stranding quality assets. The reason why upstate NY real estate is some of the cheapest in the nation is obvious: the entire region from there into Ohio, and Michigan, has been neglected for a half-century. A student should be able to come home to New York from the University of Michigan, Case Western Reserve, and Carnegie Mellon without delay and without having to spend 20 hours on a train.

If the US wants to successfully bring back manufacturing, it’s going to need a better plan than building a box in an empty field, and paving a parking lot for all workers to get there by car. The US is going to have to recognize existing assets too, like universities, and “activate” them by plugging them into faster networks. How are you going to attract top academics and researchers to the Rust Belt when they could just as easily take similar positions in Boston, Chicago, NY, and Los Angeles?

If it’s so politically hard to build rail, downgrade the position of cars, and create denser cities, perhaps a politician should make an election a referendum on these ideas and put the proposition directly to the US electorate. At least we’d finally get an answer. Because maybe, if pitched in the right way, it’s not so hard after all.

—Gregor Macdonald