Underestimated

Monday 10 January 2022

Interest rates and market uncertainty are rising as the Federal Reserve’s tightening cycle gets underway. Global stock markets have been trying to adjust to quickly changing terrain since the omicron variant, and high monthly readings of inflation, landed hard in November. The surprising extension of the pandemic initially hit markets with a classic growth scare. But this was followed in the US by an exceptionally strong inflation print in December. Since then, a push-pull dynamic has governed most outlooks as market participants attempt to gauge the likely forward path.

The pandemic itself is unusually hard to integrate as it crimps the outlook for growth and demand while at the same time bearing within itself the potential to worsen supply-chains, thus adding to inflationary pressure. Meanwhile, fears are also rising that the Federal Reserve is simply not capable of keeping up with these shifting winds, and could either wind up hopelessly behind the inflation curve, or, as bad, could find itself tightening into an economy that is already slowing naturally. It should be said, many market participants have developed a historical thesis around this tragic dynamic and they are not exactly wrong. The economy, in their view, shifts more quickly than can be met by a deliberative body, such as the Fed. For them, the Fed is like a tragic Greek hero, fated to battle an opponent already vanquished, thus blinded to the real threat now entering center stage.

The release of the FOMC minutes last week did not help the situation. Markets of course want to know how many rate hikes will occur this year, when those hikes will begin, and whether the Fed will start reducing its balance sheet, and by how much. The minutes, understandably, did not provide these answers because even the FOMC does not exactly know how the economy, inflation, and their own responses will proceed. Interestingly, however, markets did not take much comfort in recent producer price data showing a potential peak in prices both here, and in selected EU countries. That suggests markets are almost singularly focused not on macro data points, but what the Fed may do—especially, if the Fed is about to make, or has already made, a mistake.

A critical sequence of events is about to unfold, however, that should provide clarity. First, Fed Chairman Powell will have to appear publicly at his confirmation hearing starting on Tuesday 11 January. It’s likely that Powell will be called upon to not only defend the Fed’s approach taken over the past two years, but to state his overarching philosophy that he brings to the job. One characteristic of Powell that readers should absolutely consider, is that he’s the first Fed chairman in a long while to use language effectively—a far more comprehensive use of language, that actually helps his own cause. Previous Fed chairmen tended towards one-note messaging, and language that tended to land with a thud, extending the uncertainty and confusion. Powell by contrast is a robust explainer, offering not only the likely path of policy but always fleshing out the competing pathways, which together makes for a fuller picture. A critic might say Powell says what everyone wants to hear. But what if a definition of what everyone wants to hear is less about pleasing everyone, and more about addressing the trade-offs to policy so comprehensively that listeners feel he’s very on top of things—and paying attention to all the moving parts, not just a few?

The second major event of the month will surely be the Wednesday, 12 January release of CPI—the consumer price index for December. US treasury bond yields have been rising strongly in advance of this release, even as many forecasters anticipate the data will suggest inflation has already peaked. The yield on the US Ten Year has risen quickly, from 1.4% on 17 December to 1.77% last week. This has delivered even more punishment to high growth equities in the software, fintech, and biotech sectors and has also pounded away at names in the solar sector like Enphase and SolarEdge. Enphase, for example, has been cut in half, falling from over $280 to $145 over six weeks. The carnage has also moved like a wildfire through battery, lithium, EV charging, and other cleantech names.

It’s not clear, however, that even the specter of an inflation peak will calm markets. After Wednesday’s CPI, markets will have to wait a full two weeks until the actual FOMC meeting adjourns on Wednesday 26 January. Something to bear in mind is that markets tend to price in either the worst, or the best, economic outcomes and right now is no different. Shoot now, ask questions later is the apt phrase here. Interest rates up, and all equities down outside of industrial cyclicals, is the current market mode but these rotations have tended not to last in previous attempts over the past year. Here is one example: if the market really believes the Fed is going to have to be far more aggressive, by starting rate hikes first thing in March, then US treasury yields, having currently priced in the hikes, are likely to turn tail and head back down again to price in the next change in the sequence—a Fed so hawkish that it slows the economy.

The energy transition itself is not likely to be hurt sustainably this year by these machinations. Interest rates remain exceedingly low, and if inflation has indeed peaked, then the income stream which flows off wind, solar, and battery storage projects will not be discounted in any way that’s damaging. Indeed, if inflation has peaked, then ultimately, so have interest rates. And the value of dividends will look better than ever.

The one scenario that could indeed cause a bit of a crack-up in the global economy would be an actual growth scare—one that combines the tightening cycle with something unexpected, say, coming out of China. Perhaps the unfolding awareness that XI is not very competent—how he’s fallen into a bunch of own goals in his attacks on Hong Kong and internet companies, hurting his own cause—may convert to a sustained market worry. Such an impression would take on fairly scary implications if China’s economy were to falter, because markets may decide that Xi is incapable of handling a crisis. Interest rates and inflation concerns in such a scenario would disappear quickly, and the macro outlook would convert to disinflationary concerns. Battery, lithium, solar, and EV names would then have to contend with a major disruption of the current trend which, by the way, is very much led by China.

This is as good a time as any to remind: while energy transition can draw temporary succor from slow growth and low interest rates, over the longer term energy transition does best when the forward momentum of economic growth is sustained. The world needs capital to fund energy transition, and nothing hurts capital availability more than a major contraction in world trade or world GDP, and associated liquidity. Let’s hope this doesn’t happen. If you take the view that Powell is one of the better, more aware, more widely focused and experienced Fed chairman we’ve had in a while, then the probability is strong that he will guide the economy out of its crisis phase to a period of normal growth, with only a moderate if bracing flutter as we pass from one regime to the other.

Complex technological achievement tends to occur after trial and error and many iterations. But that is far less the case with the very singular Webb Telescope. Readers are encouraged to continue thinking and pondering about newly acquired potential in today’s civilization to engineer spectacular solutions, in ever shorter periods of time. The history of flight and of space exploration—as in other sectors like medicine, offshore wind, or energy more generally—has been characterized by constant experimentation and refinement which eventually produces capable solutions that can stand on their own. But in the past two years, we’ve been treated to seemingly new paradigms. The vaccine development pathway was shockingly rapid, for example. And in the case of Webb, one can’t really harken back to a phase of trial and error that would plausibly inform such a unique project. Sure, we’ve been going to space for over 60 years. But the Webb project had once chance only to succeed, having to face a kind of Death Valley in its unfolding, across 300 single points of failure. Perhaps the wildest feature of the telescope is the five layer sunshield, made of a gossamer thin material called Kapton. Without that shield, without all five layers working to block the sun’s heat, Webb simply wouldn’t function as intended. Its mission is to measure infrared light, much of it barely remaining or discernible from the big bang. The improbably fragile but effective sunshield will block the 130 F temperatures on the hot side, from seeping through to the cold side where the telescope needs to operate, at temperatures around -290 F. By the way, Webb has now fully unfolded not only perfectly, but quickly.

In careless hands, concepts like The Exponential Age can get very slippery and undisciplined. There’s a reasonable and responsible version of this idea however, and it behooves us to ask whether the pace of technological development has once again returned to a phase of acceleration. Perhaps many readers remember University of Chicago’s Robert Gordon and his compelling thesis that technological advancement had measurably slowed down. It’s possible that in many sectors, however, we need to consider the opposing idea: that innovation and the actual deployment of new solution-oriented technology has once again started to take off to the upside.

Predictions are hard, especially long-term predictions, but sometimes these come close to target. Here is a passage from the New York Herald of 7 May 1922, in a piece titled What Will the World Be Like in a Hundred Years. Primary source link: The US Library of Congress.

The people of the year 2022 will probably never see a wire outlined against the sky: it is practically certain that wireless telegraphy and wireless telephones will have crushed the cable system long before the century is done. Possibly, too, power may travel through the air when means are found to prevent enormous voltages being suddenly discharged in the wrong place.

Coal will not be exhausted, but our reserves will be seriously depleted, and so will those of oil. One of the world dangers a century hence will be a shortage of fuel, but it is likely that by that time a great deal of power is obtained from tides, from the sun, probably from radium and other forms of radial energy, while it may also be that atomic energy will be harnessed. If it is true that matter is kept together by forces known as electrons, it is possible that we shall know how to disperse matter so as to release the electrons as a force. This force would last as long as matter, therefore as long as the earth itself.

Oil, and more specifically oil demand, is coming to a moment of truth in 2022. Before getting to the terms of that moment, let’s set the context. Many market players have worked themselves into a feverish pitch of oil scarcity, while at the same time never really addressing the numbers adequately: doing so would chip away at their preferred narrative. It is frankly a tad embarrassing to see people swept away emotionally on a tide of price strength, despite the fact that precisely nothing has altered the course of global oil demand higher. Nothing. Indeed we are on the same, if not a slightly lower, trajectory of demand than most discerned back in 2019. The Gregor Letter has already cited a key example of how price distorts thinking in markets. But it’s worth reposting this passage from Bloomberg to bear witness to how future ideas about oil demand can be completely upended by daily price action.

In June of 2019, a fifth of those surveyed said that oil demand would peak as recently as February of this year, more than a third of investors said that demand would peak in just a few years, by 2025. In the first four surveys, the majority of respondents said that oil demand would peak within this decade.

That is, until Bloomberg Intelligence’s most recent survey last month — in which only 2% of investors responding said that oil demand would peak before 2025, and fewer than 40% said that it would peak before the end of the decade. More than a third of investors responding expect demand to peak between 2025 and 2030, but nearly the same number see that peak happening later, between 2030 and 2035.

Before we address some moderately legitimate supply side concerns, let’s state the obvious: global oil demand remains firmly on track to enter a sustained plateau at around 100 million barrels per day, (starting with the demand numbers of 2018 and 2019) not only this year, but next year and the year after. According to both the EIA in Washington and the IEA in Paris—both of which, by the way, have been gently revising downward annual demand totals for the years 2018-2021—oil demand in 2022 will roughly match 2019. Nice recovery you got there, but sorry, that is not “growth” or a new “upcycle.” In the same way it would be inane to declare that “oil demand is on the decline!” because of the smackdown which took place in the pandemic year, it is now pretty silly to assert that a new oil cycle is upon us. This was the same talk that took place after the great recession, by the way, when market participants were similarly fooled by the base effect. Oil recovered to $100 a barrel by 2012-2013, and then had to face a new problem: demand that did indeed grow, but, at a far slower pace. As Richard Feynman once said, “You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Based on current media coverage, you might be led to think that oil demand had fully recovered all the losses of the pandemic. It has not. 2021 demand will come in at least 3 mbpd less than 2019. The 2022 forecast above, meanwhile, remains just that: a forecast. Data note: the above data comes from EIA Washington which mostly takes its forecasting cues from IEA Paris. Both agencies have dialed back 2019 demand levels from 101-102 mbpd to 100 mbpd, and both the 2020 and 2021 readings have also been pushed down in recent revisions.

As a previous letter laid out, a better route to gauging this year’s demand is to break the world into two parts, OECD and Non-OECD, and ask ourselves the following question: can demand growth in the latter outrun demand stagnation or even declines in the former? Can that equation, which has worked for nearly a decade, carry onward? Increasingly the answer is: barely, if at all.

For this next chart, we switch agencies from EIA to IEA, as the latter is more current on this sub-series. Here, please notice how OECD demand rebounds further this year, but still winds up 1.6 mbpd below the 2019 level. Can the Non-OECD make up that shortfall? How perfect: the projected 2022 Non-OECD recovery is exactly the same as the 2022 OECD shortfall, using 2019 as the base. But as you might suspect, there’s a problem with that.

While conservatism in oil demand forecasts may have been required at the front end of EV adoption in China, the mighty S curve is now in play. In other words, in a car market that has run at roughly 25 million units for a while, even a million new EV on the road was not going to move the demand needle too hard. But with China expected to have put at least 3.5 million new EV on the road last year, thus taking 13% of market share, and 5.5 million EV this year, which could take as much as 20% of market share, the time to seriously question oil demand growth in China has arrived. Ask yourself: if global oil demand in 2022 can at best match the level of 2018-2019, what hope does demand have to go higher in 2023, given demand changes in the OECD, and now the world’s largest car market going electric?

For a decent portrait of OECD demand declines, we look to California which has long been an epicenter of post-war car culture. Despite having grown its population by nearly 6 million people to nearly 40 million total, in the twenty years from 2000 to 2020, the Golden State has managed to suppress road fuel growth to a sustained oscillation. Now comes Work-From-Home (WFH). WFH will not be a factor in construction jobs, industrial jobs, health care or teaching jobs, or Non-OECD jobs. But, WFH will be a major dynamic going forward, well beyond the pandemic, in high-tech jobs. In other words, in California. And, in other highly educated urban areas across the US, in Europe, and developed Australasia.

As always, we throw out the pandemic year of 2020. It tells us nothing beyond dependency. But 2021 petrol demand in California, which in this chart annualizes data through the first 9 months of the year, is a nice reflection of the OECD recovery overall. And it’s weak. The fifth largest economy in the world, which does not have particularly great public transportation, yet managed to hold petrol demand growth in check for two decades, is now seeing EV market share rise above 10% while at the same time transitioning to a decline in commuting due to WFH. This is a decent proxy for how things go from here in the OECD. Actually, it’s happening already. OECD oil demand peaked 16 years ago, and is now about to decline again after a brief hiatus in 2014-2017.

There is however an emerging case to be made for firm prices, because of supply. In short, supply is not as elastic as it once was for the following reason: the oil industry sees the end of growth, and is wisely choosing to invest less. They made that decision not because of ESG investing, or green policies, or Joe Biden, or Greta Thunberg, or whatever lame excuse political observers latch on to these days. No, they made that decision starting years ago. Seriously: what would you do if you saw EV sales in both China and EU surging towards a 20% share? Increasing your investment budget would not be the answer.

Thus, we face a rather tricky situation in the years ahead where demand growth, in the view of The Gregor Letter, will not be rising. This will deepen and extend the aversion to investing in new supply which, surprise, will often lead to firm oil prices. But price declines on the EV side of the ledger—after we get through semiconductor and lithium and battery capacity issues—will carry onward. And the price points and operating costs of both personal EV and commercial EV will continue to move lower compared to owning, leasing, and operating ICE vehicles. So if those firm oil prices are sustained, that will only serve to make the transition to EV move faster.

It is too soon to forecast global oil demand to enter outright decline. But it is likely a far more serious forecasting error to anticipate that global oil demand will continue rising.

While electrification of transport is an imperative, it’s important to reflect that many problems associated with the car will not be solved by EV. Much of the developed world saw its greatest expansion in the post-war period, and that took place concurrently with the broad adoption of the personal automobile. If you are an American, you could possibly convince yourself the configuration of car-dependent residential development finds its greatest expression in the US. But one only has to drive in the suburbs of London, Paris, Toronto, or Auckland to confirm this landscape can be found everywhere. Cities and their environs therefore are not particularly friendly places for pedestrians or cyclists, and especially not children.

Worse, late phase ICE design has increasingly migrated towards gigantism. The child you see above, before a Range Rover, would be at least as invisible against many American SUV models, and that’s not to mention jacked-up customization that often takes US trucks to even higher elevations. Moreover, the electrification of personal cars does nothing to abate the ongoing high costs of automobile infrastructure. Have you ever taken a look at the portion of the California budget devoted to streets, roads, and freeways? It’s not pretty.

While it’s true that lifetime running calculations for total emissions clearly favor EV, it is still the case that transitioning to EV places a call on natural resources. And wouldn’t it be preferable, frankly, if we could combine the downshift away from ICE vehicles to a configuration that at least combined a stepped up pace of investment in electric-powered trains, alongside EV?

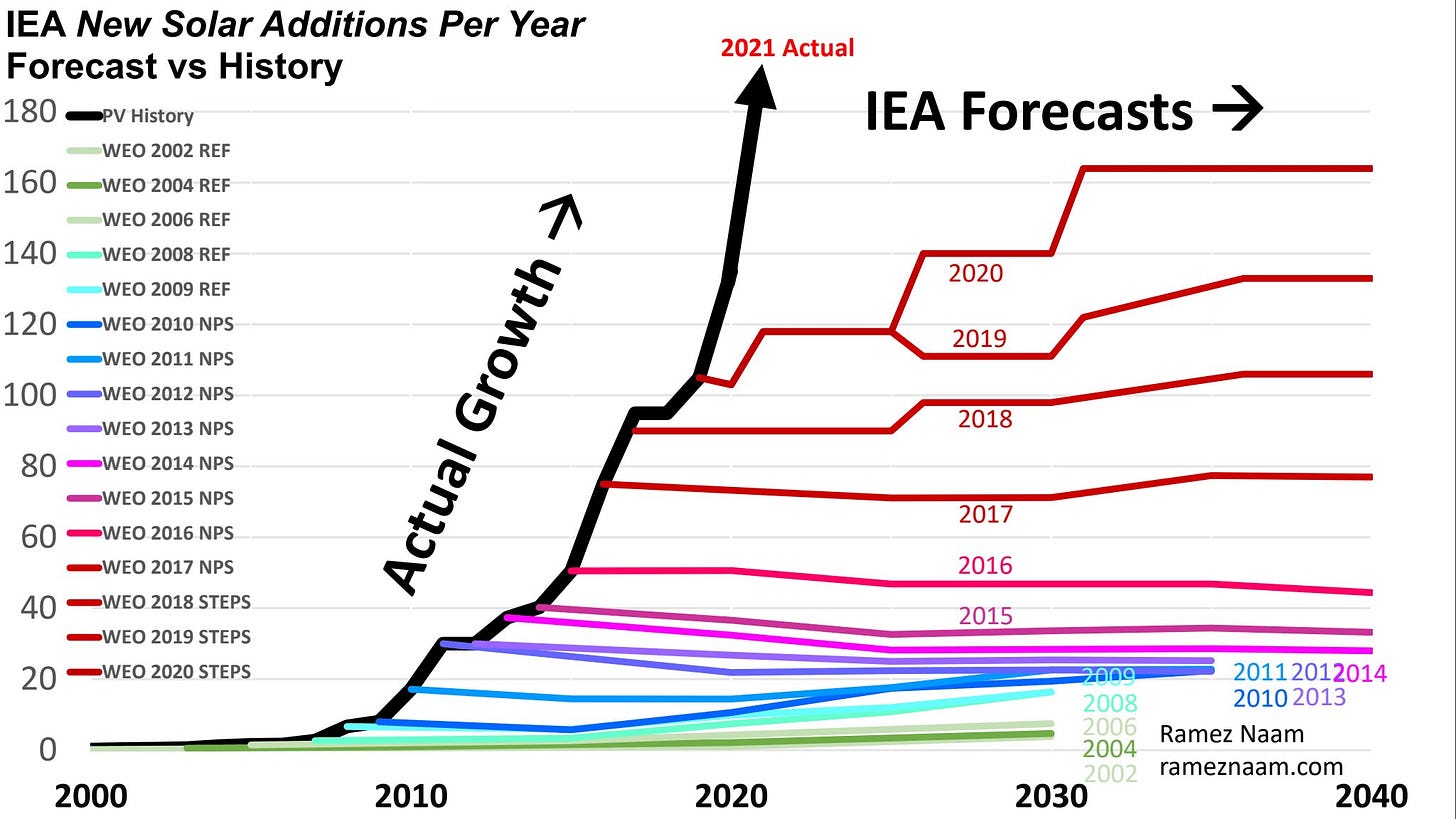

The forecasting and modeling errors around the buildout of new energy are well known. Nevertheless, it’s useful to observe how humans both over and under estimate tech progress, because a key lesson keeps arising: it’s fine to be skeptical of growth, but not when growth begins to consistently reveal itself. And that’s the error that both the EIA in Washington and IEA in Paris made last decade, when solar power began to grow strongly. Each year, after reviewing the previous year’s growth, both agencies (but IEA especially) would simply plug in a linear continuation of that growth, always failing to recognize both the base, and the growth rate.

The history of this error can be seen in the chart below, which comes from a recent deck put together by Ramez Naam. | Link to deck here: A Cleaner Future. | For readers not familiar with this type of chart, the actual growth record is represented by the thick black line, and the each year’s forecast since the year 2002 is included. All those IEA forecasts share one common element: a linear growth projection that simply takes the GW deployed in the previous year, and posits the same quantity of growth will occur in each of the following years. It would be like forecasting that Apple will sell a million iPhones next year because it sold a million last year. That’s crazy of course. Because nowhere can you find such linearity in the adoption of cars, washing machines, radios, televisions, or refrigerators.

All this said, the IEA has started to undergo a change, after absorbing the problematic influence of its projections. The Gregor Letter covered this in the 18 October edition Tech Sparks, and the way Kate MacKenzie, formerly of the Financial Times, deftly reported on the change.

Perhaps an emerging lesson therefore is that now is not a good time to underestimate human potential. Society is making not just great advances, but advances at high speed. There is admittedly understandable concern that we are not moving fast enough, for example, to really counter the inputs to climate change. But when China sells nearly 6 million EV this year, and the world deploys 200 GW of new solar this year (and maybe more), it may be time to hit the pause button on pessimism.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.