Visibility Improving

Monday 7 September 2020

The shape of the US recession has come into sharper relief, narrowing uncertainties on the likely path forward. Simply put, the shock of the pandemic is now very much receding, leaving altered economic behavior, and a standard recession in its wake. The US labor market has roughly clawed back half of the original jobs lost, as demand in the sectors most sensitive to social engagement have started to return. This is moderately good news, because we’ve come to understand better how these lower paying jobs took the biggest hit in the pandemic’s first wave, as higher-paid professional jobs more suitable to working from home were retained. Today, many now refer to these past six months as the K-shaped recovery, as employment conditions for one group held steady, while the fortunes of another severely declined.

However, it appears the recession is about to enter a new phase, one not unexpected or surprising. Workers from all wage groups are now experiencing permanent job loss. They are not being called back in many social-sensitive industries like airlines, education, and hospitality. And many higher-paid professional workers are also being let go, for the simple reason that an economy running well below capacity begins to affect everyone. In Friday’s job’s report, we learned that core unemployment, after dipping in July, rose again. As Jed Kolko, a private sector economist and contributor to economic coverage at the New York Times explains “unemployment is now shifting from temporary to permanent.”

The pandemic has understandably made a bit of a mess of all economic data, as shock effects are not easily absorbed by time series which more typically cover cyclical rates of change. The headline job-creation numbers, for example, are themselves not as useful because it’s simply hard to juggle waves of workers laid off, waves called back, while also accurately interpolating between those newly laid off, temporarily laid off, and those suffering permanent separation. To be specific, US jobs data is largely modelled, and these are very difficult shifts to model. As former White House economic advisor Jason Furman wrote, “The recovery has been rapid but this is still the easy part of it—with the harder part ahead.” Furman went further, “The household survey showed 3.8 million jobs gained, but it also showed 3.1 million of them came from temporary layoff. Recalling people from layoff is easier than creating new jobs.”

Yes, here comes the harder part. Readers will recall that The Gregor Letter base case has foregrounded, since May, a singular question: what would be the duration of the recovery after the very large effects of the initial shock had passed? That answer is finally becoming more clear. First, some of the larger downside risks have now clearly dissipated. These would include the risk of the stock market returning to test the March lows, or, another national shutdown. Without a vaccine, but also without any coherent strategy, Americans have largely started to handle the pandemic in the same way societies approached pandemics in the pre-science era: through tactical behavior change. And tactical behavior change works. (For example, if you have not read Steven Johnson’s coverage of London’s 19th century cholera outbreak, The Ghost Map, well, now is the time). Mask-wearing, distancing, and other forms of ringfencing have all taken root. The solutions are not perfect, and adherence in the US shows many gaps. However, it’s enough to start removing downside risk.

But we are left with upside constraints, unfortunately. Assuming a new administration comes to Washington in January, they will no doubt have a long-needed national pandemic strategy ready to go immediately. But that will not put the pandemic back in the bottle. And this will not restore changes to commuting and working to previous trends. More concerning is that until an actual vaccine is safe and distributable, any recovery will be capped. In remarks just this past Friday, Fed Chairman Powell told NPR, “the recovery is continuing. We do think it will get harder from here…”

The only change to The Gregor Letter base case therefore is an increase in the degree of confidence in a longer duration recovery, one that will take all of next year, and a bit more. As previously acknowledged, however, if a new administration rolls out a crackerjack program of smartly targeted policies from pandemic management to economic stimulus—especially infrastructure investment that is distributed broadly from cities to more rural areas—then the recovery could accelerate enough to make consumers and employers “feel” we’re very much on our way. That said, March 2020 to March 2022 is just 24 months, and right now, is the best model for how this storyline will proceed.

Areas of the US stock market have become extremely overvalued, but clearly investors are anticipating a new energy era. The June 13 edition of The Gregor Letter addressed not only Tesla, but the flowering of SPACs—special acquisition vehicles—which are (in some cases) front running VC and private equity by delivering emerging companies in the battery and EV space directly to the public. And they are doing so rather quickly. A notable entry this week was the announcement that another blank-check company, Kensington Capital Acquisition would functionally bring to market a Silicon Valley battery company, QuantumScape. The company, which is working on a more efficient solid-state technology, has already received investment from Bill Gates, the Qatar Investment Authority, and Volkswagen.

While it’s impossible to forecast the contours of a future green boom, clearly market participants are anticipating a policy-push from a Biden administration; one that would leverage trends already in place. What’s been called the Green New Deal Trade, or perhaps just #GNDtrade, has significantly lifted the share prices of EV plays, electronic equipment makers, renewable-focused utilities, and solar companies. While this investment approach certainly comes with a rationale, the landscape ahead is rather tricky. Global share indexes have taken their cues from easy monetary policy—many of them now at least approaching, or in the case of the US, exceeding previous highs. Trying to navigate an emerging fundamental story, while at the same time being aware of very stretched valuations, will not be easy especially with an election dead ahead. For those looking to invest in the Green New Deal, there may be a dry valley to traverse between our current location, and next year. Last week’s correction in the Nasdaq was impossible to predict, but inevitable all the same, for example. And it remains unclear how much of a further correction is needed; or the potential ancillary damage that could be unleashed on other markets should super mega-cap technology names falter badly.

Market anomalies must also be considered. At the end of trading last week, it was revealed Softbank may have been the whale in technology names this entire summer, coming into the market and purchasing massive volumes of call options. Such purchases function as demand because market makers, who sell those call options—indeed, who create them as a service to the buyer—must then turn around and hedge their own exposure by purchasing shares outright. The net effect of this hypothecation is quite simple: strong upward pressure on technology share prices. Last week’s 10% decline in the Nasdaq also bore the footprints of the trade, because outsized inventories of options—in this case, call options and their associated offsetting hedging positions by market-makers—can indeed accelerate both the upside and now downside price action. The fundamental thesis, therefore, that technology as a sector was a win-win proposition for investors during the pandemic has become a classic case of market reflexivity, as first articulated by George Soros.

The outlook for petrol-powered transportation growth is bearish, full stop. In a recent multi-case scenario, Morgan Stanley projects that in a post/emerging COVID world, transportation spending will be lower in all cases compared to the past five years. The declines are not eye-opening on an absolute basis—just a percentage point lower, mostly—but as readers understand, energy markets entirely take place at the margin. For US transportation spending to step-down from roughly 16.5% to 15.5% is a big deal, especially when Europe will track similarly, if not moreso.

When faced with the most typical question therefore about global oil demand going forward, it is not necessary to forecast a brand-new world that looks radically different than the one pre-COVID to conclude profound changes are indeed underway. Rather, all that’s required to stick a peak in global oil demand growth is a sustained shift at the margin, one that constrains oil demand from going higher. This is increasingly looking like the most plausible outcome. (N.B. - the histogram chart in the Morgan Stanley web page isn’t behaving quite right, and needs to be expanded through enlargement first, before it will fully elongate and present itself in a visually discernible form).

Gold price behavior offers a useful signal to everyone trying to gauge the duration of the recession, and the prospects for an industrial recovery. Like all financial instruments, gold is an imperfect indicator to the extent it falls into the grip of human emotions and crowd behavior. However, because The Gregor Letter has as its primary focus the economic conditions which both surround, and which are also affected by, our current energy transition, it behooves to keep hammering away at the issue of interest rates and deflationary or reflationary pressures. Our current location in the business cycle and the forward prospects for interest rates are exceedingly important factors if you have as your primary focus investment, and even moreso, the outlook for climate-focused infrastructure spending.

PIMCO, for example, recently published an excellent essay in which they’ve identified (correctly, imo) the most durable driver of gold prices: changes in real interest rates on government bonds. Because gold is an asset without any yield, it is challenged to compete in a world when other assets either pay attractive dividends, or offer solid prospects for growth. But when economic growth stalls, when dividends fall, and when forward looking investment returns are cloudy, gold does well. And gold absolutely shines and thrives when real interest rates go negative, as they have done this year. Negative real interest rates occur when the nominal rate on, say, a Ten Year Government Bond falls to 0.60%, while the inflation rate remains above that level. Gold prices would conversely start to come under pressure if the yield on the Ten Year Government Bond started to rise, thus reducing the negative real rate, or especially restoring the real rate to a positive level.

According to this model, one can simply incorporate the behavior of gold prices into an observational screen which includes prospects for employment and job growth, monetary policy, and interest rates themselves. What does the screen tell us today? Well, US government bond rates at the long end, ten years or more, are trying to rise right now. Trying, but not sustainably rising. This may be why gold prices, after a huge advance, are pausing. Government bond rates are trying to rise, because they are trying to keep up with the possibility that all the enormous policy support during the pandemic will eventually help convert the recession to a new expansion. Government bond rates would be remiss in doing their job if they failed to start discounting an economic recovery on the horizon, so to perform their duty they are trying—and let’s call it testing—the possibility, or the risk, that economic growth turns out a bit better next year than most expect.

As we head into the election, therefore, a kind of battle is going to intensify in my view between deflationary forces that will continue to pressure interest rates lower, and reflationary forces that begin to prospect for investment returns outside of assets like government bonds, and gold. You can use gold, therefore, as yet another indicator to gauge the road ahead. Contrary to the common view, for example, that gold is a protector against inflation—a thesis that is largely anchored to the 1970s—gold has instead acted in recent decades just as PIMCO describes: a non-yielding long duration asset that is impacted just like a long duration bond, ultra-sensitive to forward looking market views about economic growth.

If gold continues to stall in price over the next few months, I will conclude that we are looking at a standard recession, that will start to lift late next year. If gold goes wild to the upside again, I will conversely conclude that government bond rates are headed back down, that the testing at the long-end will resolve into a much slower recovery. Along the way however, it will never be enough to watch gold prices alone. All the other indicators are important too. And the core-unemployment tracker cited at the outset of today’s letter is probably the most important of all.

Regardless of how gold behaves we are likely to exist for years to come in such a low-interest rate world, that policy-makers who propose large new rounds of investment spending on infrastructure will almost certainly have fertile ground on which to make their case. In such a low-interest rate world, any rightly-designed proposal to incorporate renewable energy and related incentives into the economic landscape is guaranteed to procure a positive rate of return to society.

For the first time since the Great Depression, a majority of US adults are living at home with their parents. The trend is both depressing, and indicative of severe imbalances in the US economy. The task ahead for America is not merely to survive and emerge from recession. But more importantly, to invest in itself after a dry period of 3-4 decades which has left many US states stranded, frozen in time from the 1950’s. The data comes from Pew Research.

Economic regime change is clearly the big idea of the moment, as the US may transition now to a new era driven strongly by fiscal policy. There is no question that laissez-faire approaches have dominated the American scene the past 40 years, with the only powerful adjustments coming at the margin, from monetary policy. Indeed, the last time the US seriously invested in itself, using fiscal policy as the spearhead, was immediately after WW2 when roads, schools, and other public projects were undertaken with broad bipartisan support. That brief period largely ended in the 1960’s, and now the US finds itself in a deep infrastructure deficit. One only needs to return to the US from other parts of the developed world to be shocked into realization of how far the country has fallen behind. London looks like something from the distant future, for example, compared to many US cities. The notion that we are about to tip from one era to another was articulated nicely this week in the Odd Lots podcast, which interviewed former PIMCO director, Paul McCulley.

The Federal Reserve’s newly articulated approach to inflation—which is really a major revision to old theories about sustainable levels of employment—has ongoing implications for the US Dollar. The Economist this week identified a dynamic that is likely to now come into play: if the US Dollar stays weak for much longer, other central banks frustrated with overly strong currencies may be tempted to follow the Fed’s lead. Adopting similar postures towards employment and inflation would push back against a weak USD, in an effort to weaken their own currencies. While these ideas may seem new, the dynamic is quite old: recessions and especially global recessions have long raised the incentives to gain advantages through competitive devaluation.

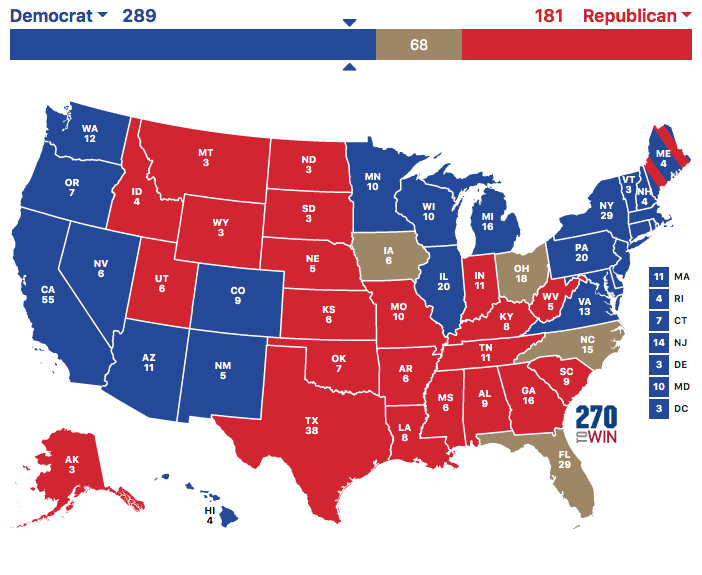

The narrative of a tightening US presidential race has fallen apart as quickly as it arose, late last month. Bumps from the Republican National Convention and the Kenosha shooting have entirely dissipated. According to CNN pollster Harry Enten, Biden’s lead is so stable, that it’s now the steadiest on record. Where Trump still has an edge is in overall confidence of his (future) ability to handle the economy, on a comparative basis against Biden. And pollsters from the Economist (G. Elliott Morris), to 538 (Nate Silver) and the New York times (Nate Cohen) are all currently chewing their way through slight adjustments to Trump’s prospects given that the economy is less bad than before. It’s not a major adjustment, but it does partly push back on the idea that Biden will easily walk away with a victory this November if the economy “feels” better to Americans.

In my opinion, the electoral map below best describes the state of the Presidential race today. The map begins with all the states that Hillary Clinton won, adds back PA, MI, and WI, and then grants AZ also to Biden. While state polls of FL and NC are quite encouraging at the moment, those states are too uncertain to put in the Biden column. Florida in particular has not been a good state for the Democratic nominee for twenty years. Very slippery, very tricky. And Ohio and Iowa truly appear lost entirely now to Democrats. As previous issues of the letter have suggested, markets should prepare for a Biden presidency. The remaining uncertainty is how much power Biden will enjoy, because Senate control remains very hard to forecast.

Despite lingering beliefs about the challenges of intermittent energy, surplus wind and surplus solar will create myriad arbitrage opportunities. Layer1, a bitcoin miner and energy arbitrager has set up operations in Texas, buying surplus wind power overnight and then selling power back to the grid during daytime hours, when demand is higher. Essentially, Layer1 is an energy storage market player, with a bitcoin operation on the side, cleverly timeshifting its own demand around market fluctuations. We are going to see storage not only more regularly paired with utility scale wind and solar facilities, but infrastructure of all kinds—especially commercial and institutional real estate. There’s no reason why the University of Texas can’t add storage and do the same. As storage expands, the cost curve will accelerate, and eventually having storage capacity incorporated into in a public building will be as common as a boiler.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

Photos: 1. Willamette River looking north, towards downtown Portland, Oregon, January 2017, Gregor Macdonald. 2. Plate from Electricity and Magnetism, by Oleg Jefimenko, 1989. 3. Gold lights/paper discs. 4. Nova North building, Victoria Station district, London, March 2020, Gregor Macdonald.

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.