War Zones I

Monday 7 March 2022

A profound demand-destruction event is coming to global oil if current high and volatile prices are sustained. OECD oil consumption peaked 17 years ago in 2005 and since that time the global oil industry has successfully made up for this shortfall by serving relentless demand growth in the Non-OECD, led of course by China. This bifurcation of the oil market’s growth prospects also happens to track differences in price sensitivity, or demand elasticity, which is much lower in the Non-OECD because each individual consumer uses far less oil, less petrol, and less energy generally. In the OECD however consumers use much more oil per capita and petrol consumption in particular still has a significant, discretionary component.

Accordingly, price shocks translate pretty quickly to demand declines in Europe and North America. Indeed, crises, recessions, and other economic slowdowns in the OECD have all been marked by either mild or in some cases severe demand declines. Not so in the Non-OECD. Even during the Great Recession, Chinese and other developing world demand mostly powered forward, despite price, and despite a slowdown in global growth. This is precisely the behavior one expects to see when a region is on the front end of initial oil adoption, as new users come to the oil market: small amounts of petrol use individually, across large populations, translating into broad demand growth collectively. The OECD, by contrast, entered its oil adoption phase over 100 years ago. In Europe and North America, supported by strong currencies and GDP, per capita oil consumption travels along at a far more elevated level—but it’s a fragile, and elastic level. Indeed, the pandemic ripped the mask off a truth that planners and analysts have known for decades: the OECD could have weaned itself more concertedly off oil a long time ago.

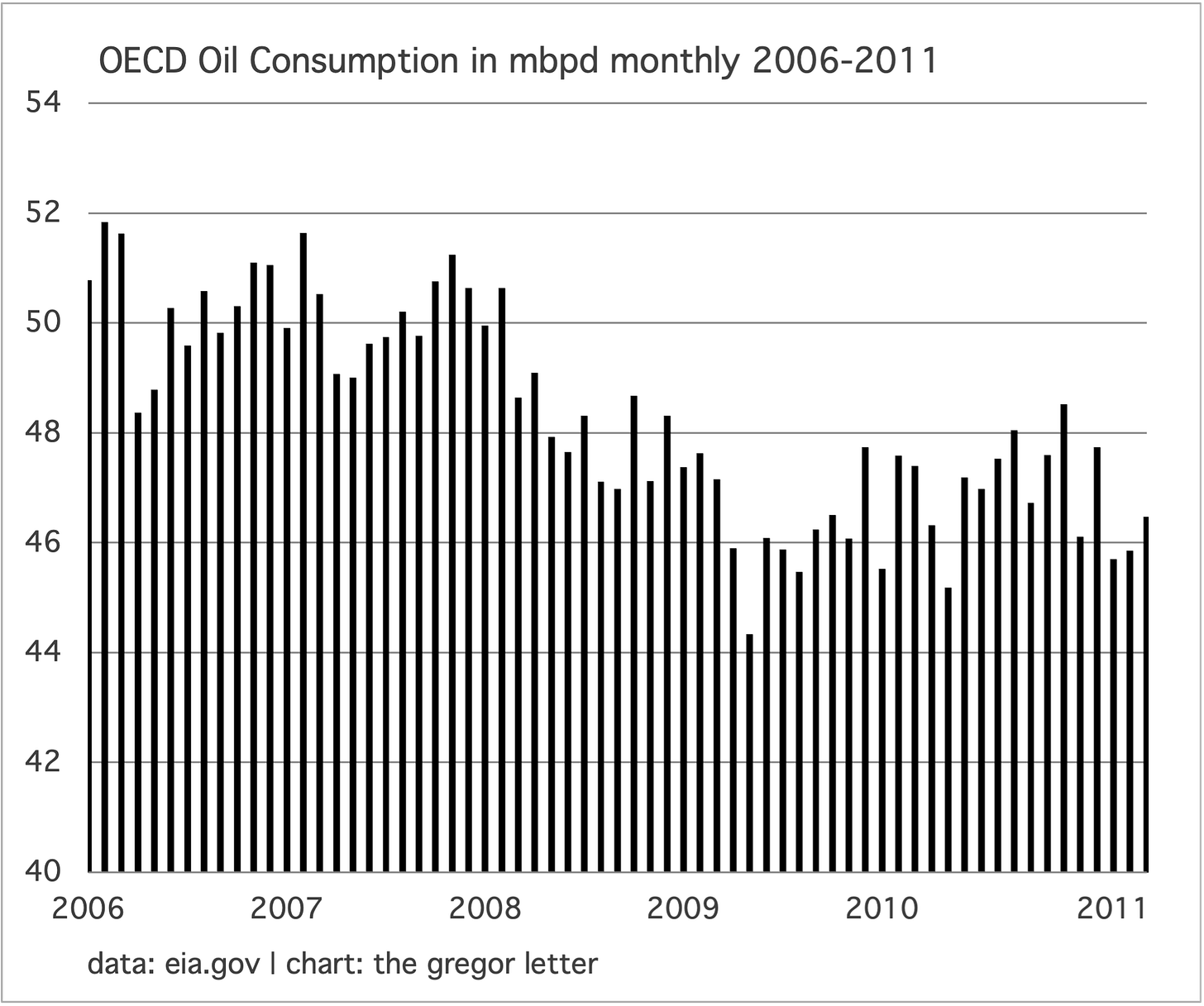

Here is a chart, for example, of the demand declines that began to set in during 2006, as the OECD came off its all time demand high of 2005. The trend downward would resolve into the heart of the crisis itself, in late 2008/early 2009. Demand would continue even lower as a plodding economic recovery played out over years. OECD annual demand traveled from a high of 52.5 mbpd (million barrels per day) in 2005 to a low of 45.7 mbpd in 2014, before recovering to 47.7 mbpd in 2019. Despite a growing population, therefore, the full crisis and recovery cycle over fifteen years saw the permanent destruction of nearly 5 mbpd of demand. That’s enormous, and it could play out a second time.

But what about the Non-OECD, where sensitivity is much lower—at least up to a point? The current price spike in oil may be the first one that brings notable demand declines not just to the OECD (as one would expect) but to the Non-OECD as well. The reason is that the Non-OECD has a new escape valve to capture demand that’s feeling the sting of high prices: electric vehicles. China sold 1.21 and 1.37 million EV in 2019 and 2020 respectively. But in 2021, China sold 3.52 million EV and is expected to sell 6.00 million EV this year. Should China’s total vehicle market reach 27 million units in 2022 as forecast, that means EV market share in China which trudged along in single digits for years—finally reaching 5% in 2020—will notch a 20% share this year. And that was the forecast before the recent price volatility in oil. The implications for global oil demand this year are potentially serious. China was forecasted to increase its oil consumption from 15.25 mbpd last year, to 15.74 mbpd this year. But a combination of both energy and food price inflation, combined with the country’s industrial base which can increase EV sales to meet demand, means that China’s demand may be flat in 2022, not falling, but not growing either.

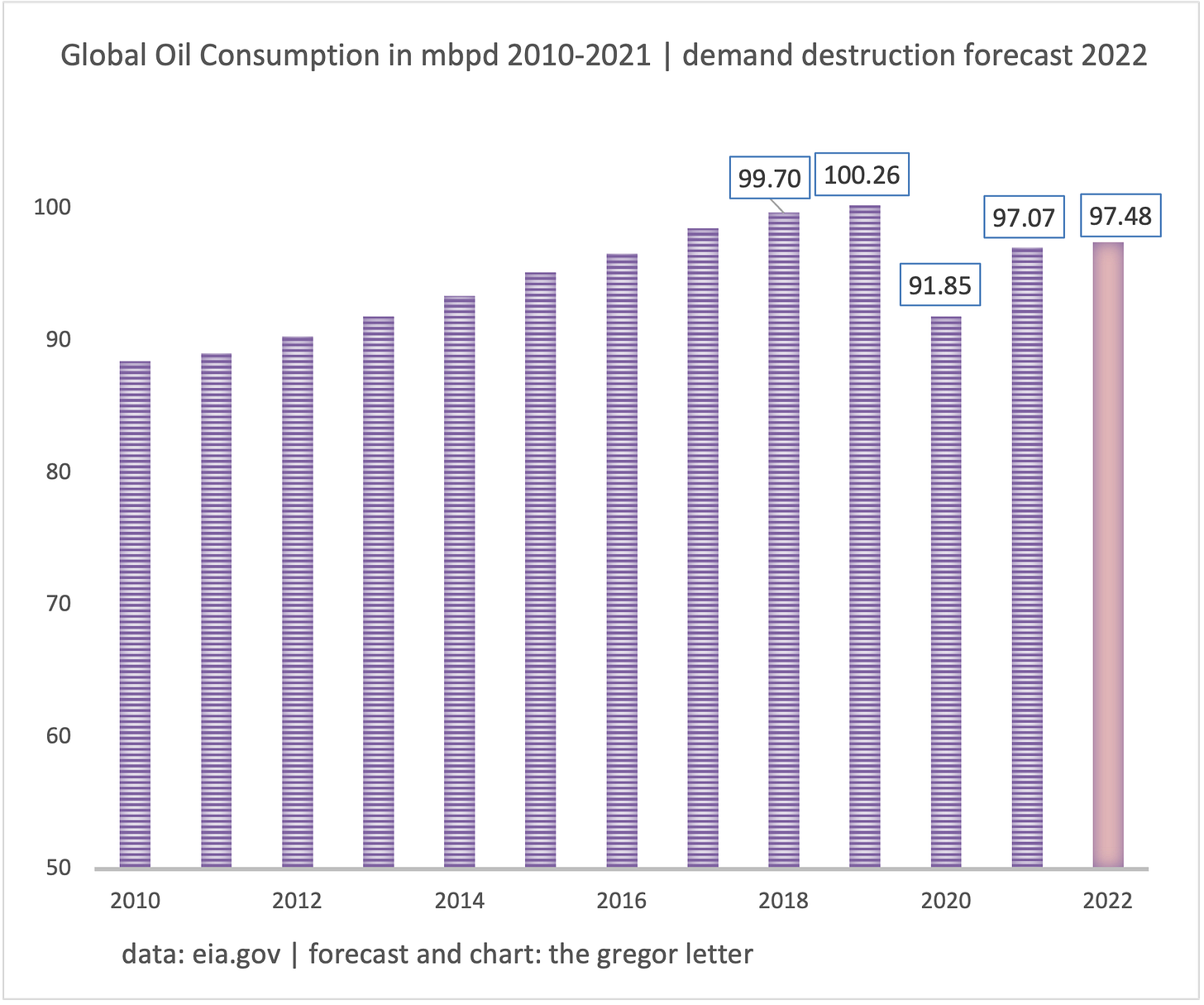

Coming into this year, the expectation of the EIA and IEA has been that 2022 global oil demand would finally make it back to the 2019 highs, just over 100 mbpd. That was not an unreasonable forecast. The colossal fiscal and monetary support ushered in by the pandemic saw OECD economies make rapid recoveries. This snarled supply chains and restored energy demand at a far faster rate than previous crises. The net effect was to push prices up quickly as global workforces struggled to fully reassemble. Still, oil in a range of $70-$80 was not high enough to meaningfully dial back the continued demand recovery. (Even if growth prospects continued to center not on the OECD, but the Non-OECD). Here is how global oil demand looked as recently as mid-February, prior to the Russia-Ukraine War.

Now, however, the global oil market is looking at a quickly emerging array of damage to demand. First, from Russia itself. While Russia produces 10 mbpd of the 100 mbpd of global production, it consumes roughly 4 mbpd of those volumes. That’s going to crash, by at least 0.5 mbpd if not more as Russia enters a severe financial crisis. Europe meanwhile is likely to enter recession, at least for a quarter, and could see economic growth under pressure for the remainder of the year. Europe was expected to add back demand this year, moving from 12.98 mbpd in 2021 to 13.39 mbpd. That’s now gone. Worse, demand in Europe is more likely to fall, from 12.98 mbpd to at least 12.8 mbpd because Europe too can now call upon EV as the new escape valve. A final flourish: sales of ICE vehicles in the EU for the rest of this year are going to be crushed. Indeed, the scale of the damage to the ICE vehicle market could be similar to the ongoing collapse of diesel sales in the UK. The very idea that consumers are going to roll into EU car showrooms this year and buy themselves a new petrol powered model is as lurid as it is comical.

In the US, meanwhile, where demand elasticity is highest in the world given our low MPG efficiency, high miles traveled, and high volumes consumed, the entire forecasted advance from 19.78 mbpd last year to 20.66 mbpd this year could also be wiped out. However, the US economy is super strong right now, with workers continuing to flood back to the workplace. Moreover, the availability of EV models at lower price points is still not sufficient to meet all potential demand. Many of the EV models Americans are most excited about—trucks from Ford, GM, and Rivian—are either not available yet or only in tiny quantities. So the US doesn’t have the same EV escape valve available in China and the EU. But just as in Europe and China, how many Americans will enthusiastically buy a new ICE car this year? US demand destruction therefore may come mostly through the petrol side of the ledger: fewer miles traveled, carpooling, a bigger call on public transit, fewer ICE cars sold. The 20.66 mbpd could easily be held to 20.00 mbpd this year.

Finally, we have to consider not just the currently forecasted global EV sales for this year, but the added bump EV will get from a sustained oil shock. The Gregor Letter has already estimated that the 10 million EV originally set to hit the road this year globally will avoid roughly 0.46 mbpd of demand growth. We now need to boost the forecast of global EV sales by at least 10%, and frankly 15% would seem more reasonable. Doing so brings EV avoided demand up to a full 0.50 mbpd. That said, it’s not easy to impute EV adoption into existing oil demand forecasts, or future ones. To be conservative, it may be best to impute demand declines in select regions as though the EV factor was already included, and then add the 15% sales surge as its own component. Here is a rough and early estimate of the aggregate demand declines the market is facing, laid out in table form.

And here is the chart, showing that a sustained oil shock has the potential to wipe out the entire forecasted growth for this year. Readers are advised to take a strong, Baysian approach to this forecast (and all others) as a very volatile year ahead will upend outlooks of every type, requiring constant updating. That said, this first attempt at a demand destruction forecast may seem conservative to many, given that it merely removes previously anticipated growth, and does not yet probe for outright year-over-year declines.

You are reading a two-part post from The Gregor Letter, the first of which is free. Part II will publish next Monday, 14 March, between the dates of the regular publishing schedule. If you are still carrying a free subscription to the letter, please consider subscribing as there are very few free posts throughout the year. To learn more, see the About section. Many thanks as always to the international institutions, agencies, and investment professionals who rely on the letter for its energy and climate analysis.

A strong moral impulse is coursing through Western societies to entirely sever the flows and consumption of Russian oil and natural gas. But without a plan to do so in phases, this aspiration is at best unrealistic and in the immediate term, mostly impossible. Russia produces 10 of the 100 mbpd of global oil output. Europe’s dependency on Russian natural gas, meanwhile, is so deeply structural that any person proposing to cut off such supplies should be required to explain why painful prices already endured for many months has not yet resulted in any kind of emergency demand response.

It is also discouraging, if not distressing, to additionally learn how many educated westerners somehow missed basic facts about how commodity markets work. Sometimes, an example from outside the commodity at the forefront of our attention (oil, of course) can help illustrate. Imagine that within one week Brazil became a pariah nation, and westerners decided it was crucial to “get off Brazilian coffee” as soon as possible. Well, there is no such thing, frankly, as westerners getting off Brazilian coffee as long as Brazil can sell its coffee exports to some other buyer. Self-satisfied western coffee drinkers under such an arrangement would only be avoiding Brazilian coffee in spirit, because a successful re-routing of Brazilian supply within the global coffee trade would keep prices mostly normalized.

To thoroughly get off Russian oil (and gas) means something quite different altogether. It means finding a path so that the entire world no longer uses the 6 mbpd of oil Russia exports out of its own 10 mbpd production. Here, commodity markets have yet another unpleasant fact to deliver: demand or supply changes of just 1 mbpd can have a major pricing impact on a market that runs at 100 mbpd. How can that be? Well, all markets are priced at the margin. But commodities are highly physical, capital intensive, and reliant on global shipping networks. Commodities cannot be distributed through the internet, where barriers are low or non-existent. Accordingly, a certain level of redundancy or cushion is required by commodity futures markets to maintain normal course pricing, and risk therefore gets priced in quickly, often prematurely, and quite often runs to both extremes.

As The Gregor Letter goes to press, for example, mere chatter to sanction the very small volumes of Russian petroleum products sent each day to the US has caused oil prices to spike further. This is how the futures market works: small changes are applied to the whole. It absorbs the implications of future policy, output, shipping, economic conditions and then puts a price on commodities to best balance future risks. If the US is going to start small, with a largely symbolic rejection of Russian oil, then the futures market immediately proceeds to price in the risk that much larger volumes of Russian oil will no longer easily find buyers. Observe for example how a synthetic form of such sanctions is already unfolding, as Russian seaborne oil found itself severely underpriced last week. When the trading arm of Shell Oil bought that oil—which by the way is in complete legal conformity with the current sanction structure—the social outcry was massive enough that Shell soon announced it would donate its windfall profits to humanitarian efforts in Ukraine.

So which will prevail in the West? The moral urgency to hurt Russia severely, denying it as few revenues as possible? If so, that means voluntarily taking on economic pain that is both immediate, and severe. The Gregor Letter favors the view that western consumers will come up to that threshold, waver, and then choose various plans to steadily remove Russian barrels over time. The IEA for example offered one such scenarios for natural gas, and proposed a ten part plan that would roll out over a year or more.

Those of us who focus on structural dependency on fossil fuels, and the myriad ways to transition away from these dependencies, should take seriously the human urge to act in accordance with humanist principles. The Russian attack on Ukraine is at once bizarre, lacking in any coherent goal, and horrific: Putin’s heavy artillery attack mainly on civilians is dark, something out of the worst phases of the 20th century. For a world looking to meaningfully, and not just symbolically, wean itself from Russian oil, most of the necessary work will need to take place on the demand side. And so, consider this: of the 6 million barrels Russia puts into the market each day, today’s letter lays out how the world is likely to withdraw demand for at least 3 million of those barrels. It won’t be pretty, it won’t be easy. But it does demonstrate how, in conjunction with better designed policy plans, the world could at least start moving directionally toward its goal.

Putin’s historic mistake is going to unleash suffering not just in Ukraine, but also in Russia. We are early still, in the course of this war. But two very grim realities are emerging. One, Ukraine’s defenses are strong enough, and Russian logistics and military planning weak enough, that the invasion is already bogged down. This has caused the Russian military to resort to a form of mindless bombing and shelling that serves little strategic purpose, and, confirms the entire theory of the war as conceived by Putin was in error. Meanwhile, the police-state back home has spun up into high gear with mass arrests, interrogations of departing travelers, newly harsh laws on all forms of dissent, and desperate propaganda. An ironic possibility emerges: in Russia, where sanctions could hover for years, the damage from this war may be more long-lasting.

Western policy makers need to harness market dynamics to guide capital through a rapid deployment of energy security initiatives. Greed, forward looking expectations, and clear investment pathways are powerful dynamics. Leaders need to use them. Observe, for example, the dynamics already unfolding from the rapid-fire announcements coming out of large EU economies, Germany especially, to embark on a new cycle of defense spending. These same forces could also be unleashed to promote the rapid buildout of grid storage, heat pumps, more extensive natural gas import and storage infrastructure, and better solutions in transport. Western populations are just old enough to forget that on an emergency basis, economies can build and deploy solutions at rates that far exceed the plodding morass that governs during peacetime. Leaders also need to get loud. Announce these plans with vigor, using specific targets, and procurement schedules. Europe and the US should, for example, not just build, but announce the intent to build grid storage on an emergency basis. Investors and markets will swoop in with capital in the aftermath of such plans, and that’s a good thing. It is not enough to shock markets with embargoes and bans. That only serves to clarify the oil and gas we’re trying to avoid. Energy sanctions will not work unless they are paired with clearly articulated solutions that both consumers, and markets, can understand.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.