War Zones II

Monday 14 March 2022

The United States is neither energy independent nor petroleum independent, except on a net basis. Accordingly, American drivers are fully exposed to the world oil price. Unlike Saudi Arabia or Russia—which both enjoy large oil surpluses, export a majority of their crude oil, and unsurprisingly subsidize extremely cheap petrol prices for their citizens—the US still relies on raw, crude oil imports to support its nearly 20 mbpd (million barrels a day) consumption habit, after deducting 11-12 mbpd of domestic oil production, and over 1 mbpd of ethanol and biofuel output.

For decades there has been confusion about energy independence—both definitionally as a term, and, as a long-term policy goal. Since the OPEC-led oil crisis of the early 1970’s however most Americans have quite clearly defined energy independence as oil independence on an absolute basis—producing all the oil we consume. The good news is that the oil balance—the difference between what the US consumes and what it still has to import—has improved greatly in the last 15 years. This is because, despite a growing population, US oil consumption is no higher than it was in 2005, and domestic production has soared, from a low point near 5 mbpd in 2008 to roughly 12 mbpd today.

But if the US consumes about 20 mbpd, and produces 12 mbpd, how could the US ever have hoped to become independent, even on a net basis? Well, the word “net” is pretty crucial in this regard. The US is a colossus of petroleum product capacity, and when making petroleum products there is a gain due to processing. The US therefore produces its own crude oil, and also imports crude oil, but then converts all of this raw crude into products that can be used domestically, and abroad. In 2020, when domestic consumption fell hard due to the pandemic, this petroleum product capacity did not shut down but kept going strong. As a result, for the first full year in the modern era (outside of a few selected months in recent years) the US became a net exporter of petroleum products. This year? The EIA expects the US to return to being a net petroleum importer.

Contrast this landscape in oil, for example, with US natural gas. For many decades the US enjoyed the benefits of cheap natural gas prices, often below if not well below world natural gas prices, because North American natural gas was landlocked—outside of pipeline exports to Mexico. And even today, with the US exporting roughly 10% of its natural gas output on the back of a newly formed LNG export industry, Americans still enjoy the price benefits of living in a country where we produce all the natural gas we need, and then some. This is what most people regard as the definition of independence. The US is absolutely natural gas independent.

The comedy of it all is that the US could have become oil independent on an absolute basis many years ago. Obsessed with supply side solutions, it just never occurs to the US to attack the demand side. Road charging programs in cities, better commuter rail, higher petrol taxes, and a more aggressive improvement in mileage efficiency could over time easily knock out several million barrels of US oil demand. Europe and the UK by contrast have pressed onward in these efforts, and are now in well defined decline.

But the US has indeed seen radical changes in the supply side of energy. That is how the US has become energy independent on a net basis—not in terms of barrels or volume, but in strict energy terms: you know, BTU or EJ (exajoules). Leveraging domestic natural gas supply, rapidly growing renewables, and exports of coal, LNG, and petroleum products, the US has admirably transformed its energy balance sheet. The Gregor Letter regularly updates the evolution of this balance sheet, showing net energy dependence of the US has declined steadily for over a decade.

America’s net energy independence without question strengthens its energy security, and has long term implications for the US Dollar, and the country’s terms of trade. Consider this fact: the US is entirely in control of its own electricity prices, determined by the cost of natural gas, coal, hydro, nuclear and renewables. But through the lever of wind, solar, and storage, the US has its destiny also completely within its control. Every new TWh generated from wind and solar frees up extra units of coal and natural gas for export. This has already happened. Combined wind and solar now account for an enormous 12% of total US electricity consumption: that’s over 500 TWh in a 4000 TWh system. And more is on the way, which will free up even more coal and natural gas for export.

Let’s review the current and true status of US energy independence.

• The US is not energy independent on an absolute basis.

• The US is not oil independent on an absolute basis.

• The US is petroleum independent on a net basis by leveraging the largest refining capacity in the world to transform raw crude into finished products. But this is fleeting, and only occurs sustainably when US consumption falls enough to tip the petroleum balance sheet into slight surplus.

• The US is coal and natural gas independent, with large surpluses of both currently exported.

• The US is energy independent, but on a net basis given the oil gap, as it builds self sufficiency across all energy sources.

Armed with so many tools, and abundant natural resources, the US has the opportunity to wipe out the last leg of its energy dependency by undertaking steps to reduce domestic oil demand. Unlike most other western nations, however, the US political establishment has long feared this third rail of the cultural landscape. It’s ironic too, given that during WW2, the majority of Americans pared back consumption of petrol willingly, if not enthusiastically. When you consider how many Americans drive a 6,000 pound vehicle to run short-trips all throughout the day, a certain long-standing thesis quickly comes into view: the achilles heel in US energy policy is not supply, but rather that the cost of driving and the price of petrol have been cheap for so long that it has masked real costs, and created a culture of waste.

Vladimir Putin’s theory of the Ukraine invasion turns out to have been entirely wrong. But this is not necessarily good news, as it potentially lengthens the duration of the war. The picture we are getting through multiple reporting sources is that Putin’s quest in Ukraine has a juvenile, almost romantic element that is so unconnected to reality that one has to ask whether Kremlin propaganda not only aims to soften the war for domestic audiences, but reflects Putin’s actual thinking. Leveraging historical fears of Nazism, Putin has tried to sell the Ukraine invasion as a welcome liberation. But on the ground, even the most pro-Russian regions in Ukraine have seen stiff resistance. Putin’s theory was that Russian forces would only have to show up, parade through the centers of numerous Ukraine cities, and a kind of low-violence revolution would get underway, ousting the current government. The reality: nearly the entire world is adamantly in support of Ukraine, and Ukraine nationalism and determination to fight is truly heroic.

In a recent New Yorker interview, Princeton professor Stephen Kotkin pointed out that Russia, and Putin in particular, are living in a golden amber time capsule, with the rest of the world having long since moved on:

What is Putinism? It’s not the same as Stalinism. It’s certainly not the same as Xi Jinping’s China or the regime in Iran. What are its special characteristics, and why would those special characteristics lead it to want to invade Ukraine, which seems a singularly stupid, let alone brutal, act?

Yes, well, war usually is a miscalculation. It’s based upon assumptions that don’t pan out, things that you believe to be true or want to be true. Of course, this isn’t the same regime as Stalin’s or the tsar’s, either. There’s been tremendous change: urbanization, higher levels of education. The world outside has been transformed. And that’s the shock. The shock is that so much has changed, and yet we’re still seeing this pattern that they can’t escape from.

You have an autocrat in power—or even now a despot—making decisions completely by himself. Does he get input from others? Perhaps. We don’t know what the inside looks like. Does he pay attention? We don’t know. Do they bring him information that he doesn’t want to hear? That seems unlikely. Does he think he knows better than everybody else? That seems highly likely. Does he believe his own propaganda or his own conspiratorial view of the world? That also seems likely. These are surmises. Very few people talk to Putin, either Russians on the inside or foreigners.

The essential problem for the world economy, however, is that the duration of Russia’s presence in Ukraine is now tied to the duration of Putin’s presidency. Without an internal overthrow of Putin’s regime, it becomes more difficult to see a path by which sanctions are lifted. And if sanctions go on for too long, that will have fairly negative consequences not just for economic growth more generally, but energy transition specifically.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shifted western policy attention to fossil fuels, placing further pressure on energy transition. The inflationary outbreak during the second half of 2021, and the extent to which it was led by upward pressure on oil and natural gas prices, had already introduced a new complication to the project of decarbonization. Now in 2022 the Russian-Ukraine war has unleashed an intensification of risk perception, and a new obsession with energy security. And, despite how many different permutations of this geo-political event can be utilized to accelerate the deployment of clean energy infrastructure, focus is going to remain on natural gas prices in the EU, and oil prices globally, until some resolution is brought to bear on these two main pinch points.

Using the history of sanctions against Iran, there really is no question that Russian oil production is going to fall. Domestic oil consumption in Russia will fall. And Russia’s total output is just like any other industrial complex, in that it relies on equipment and maintenance capability that largely arrives through a global supply chain. Well, that chain just broke, for Russia. True, Russian barrels have not been sanctioned yet globally, despite the mostly symbolic ban on Russian petroleum products previously imported by the United States. Accordingly, Russian barrels will continue to find their way to market. And every Russian barrel that continues to be sold on the global market—even if many of these barrels are bought by China, India, and other non-western countries—represents a barrel that is not competed for in the rest of the market. But this leaves the question: how to soften the blow of an erosion in Russian oil output, and, that any exported barrels from Russia may come under various pressures?

Last week’s letter suggested the first round of mitigation will come through price-driven demand destruction. To the extent Russia has historically provided about 5-6 mbpd to the global market, The Gregor Letter analysis suggests that as much as 1/2 of this supply could be offset by reduced demand, entirely removing the 3 mbpd of demand growth which forecasters expected for this year. Another 1-2 mbpd could be offset should a parlay of fortunate supply events to unfold: from an Iran nuclear deal, to better production in Venezuela, and possibly even Iraq.

But it’s pretty clear that the world will have just as much difficulty mitigating Russian oil as Europe will in getting off Russian natural gas. These dependencies are quite structural. And until those dependencies are solved, policymakers are going to be increasingly wrapped up in petrol taxes, fossil fuel security, and the political fallout that will surely arrive as opposition parties agitate for more attention to oil and gas.

The hapless performance of Russia’s military in Ukraine has spawned a new genre of social media humor. Much of this has centered around short videos of Ukraine farmers, often driving John Deere tractors, towing away abandoned tanks and other rolling equipment. This spoof account, below, decided to get in on the action with a deadly funny mash-up:

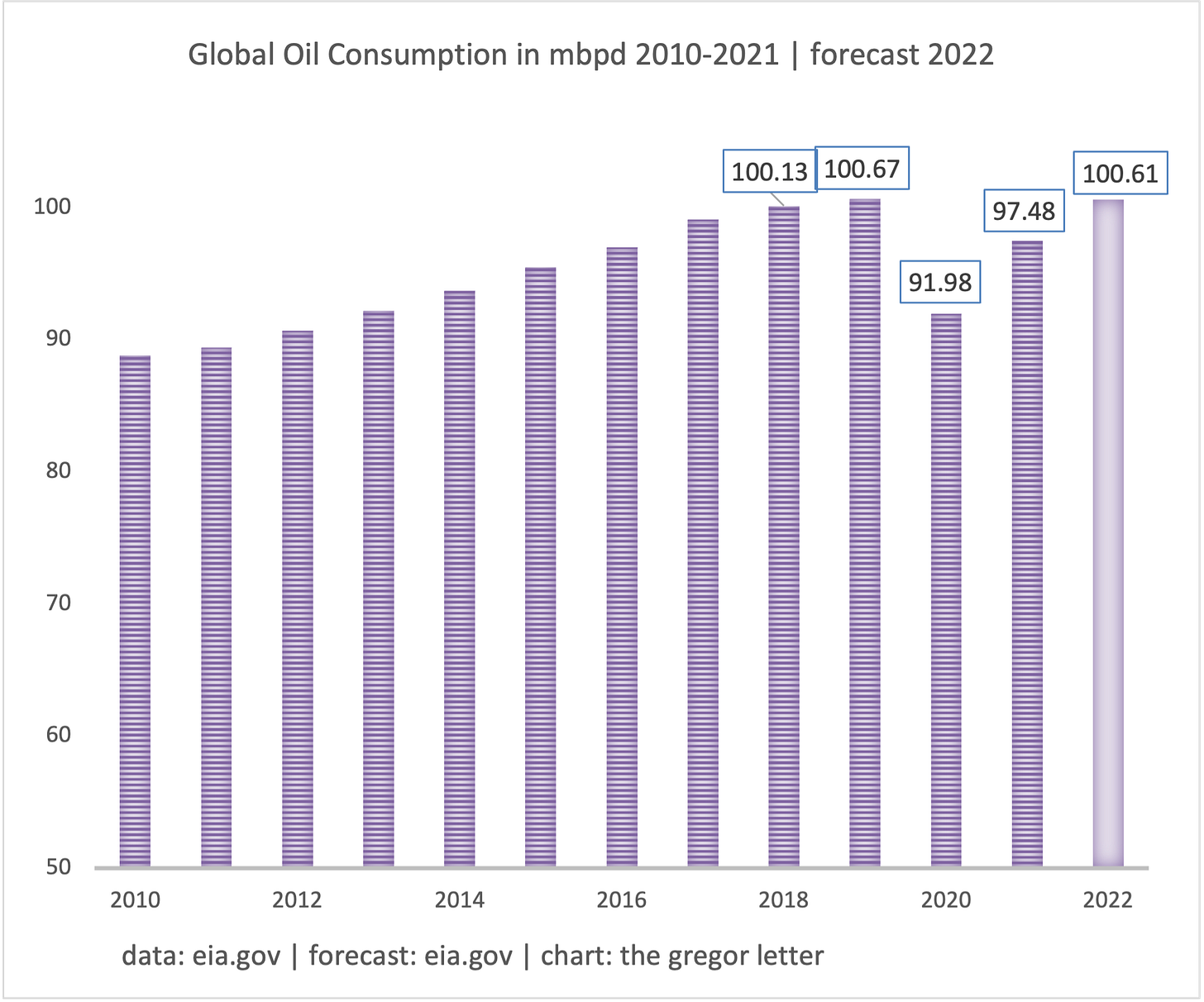

EIA very slightly revised upward its trailing estimates of past global oil demand. In doing so, it brought 2018 levels above 100 mbpd, and pushed 2019—the last normal year for oil demand—to a new high. But the EIA did not touch (yet) its estimate of this year’s oil demand at 100.61 mbpd. That’s going to change, however, as the IMF likely downgrades its estimates of 2022 global growth. This will in turn push the EIA (Paris) to downgrade its own estimates of oil demand, and EIA will soon follow. All this said, The Gregor Letter will be keeping very close track of changes in demand forecasts, and each issue now will likely address the below chart.

A 1997 paper on oil shocks and interest rate hikes by Ben Bernanke is starting to get attention. Late last year, I began to ping various twitter conversations with the general findings of the paper, and now Paul Krugman has also dipped back into the well.

In short, Bernanke and his co-authors found that oil prices act as a kind of grease to the world economy, and tightening the supply of this grease through higher prices, surprise, tends to trigger slowdowns all on its own. Accordingly, interest rate hikes themselves in such periods tend to do more damage than policymakers may have realized. As the FOMC meets later this week to hike interest rates, it would indeed be fascinating if Chairman Powell referenced these ideas during our current war-pressured spike in global oil prices. | see: Systematic Monetary Policy and the Effects of Oil Price Shocks (1997).

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.