We Are Unhappy

Monday 30 October 2023

Because the discipline of Economics is irrevocably tied to real, material conditions, it’s incumbent on the profession to explain the current American gloom about the economy—pushing aside in-vogue focus on partisanship, and media influence— and return to fact-finding that supports the unhappiness. By now, just about everyone has ruminated over the large gap that’s opened up between broad measures of the economy, wages, and savings, and surveys of economic sentiment. The Federal Reserve for example just released its Survey of Consumer Finances and all the news is stellar: wages, wealth, and jobs are way up. Moreover, workers at the bottom of the wage scale have enjoyed a serious boost in pay. And importantly, with inflation coming down, real wage growth has been encouraging. In other words, the US economy both in its macroeconomic condition and in its particulars is doing well. Indeed, it’s booming. And yet, here is just one illustrative chart about the confounding gap between perceptions, and the data, from The Economist magazine:

Supporters of the Biden administration are freaking out, understandably, because many longstanding economic policy ideas around infrastructure and better distribution of investment into poor regions have come to fruition—but where are the thanks? One of the most impressive outcomes of the past few years is that not only does the US have the lowest inflation now among western nations, but the economy continues to pump out job opportunities. So in the near term, people can be forgiven for throwing up their hands and wondering if Americans have lost their minds. The thing is: an appeal to zombie-ism may sate frustration temporarily but that is capitulation, not analysis. Americans have neither gone crazy, nor are they duped into thinking their finances are bad (when they’re actually good) by the media. Those choosing these explanations now are likely to be embarrassed later.

And yet, no one has a conventional economic explanation for the gloom. If there is a cause that has any enduring merit, it would, of course, be inflation: not the rate of inflation which is surely coming down, but rather that we are still in proximity to the general inflation itself, and the way it delivered a notably higher price level in all goods and services. If consumers are still mentally anchored to this experience—which may have only been partly mediated by wage growth for several cohorts of workers—their alarm would take time to abate. For, as we know, humans mostly project present experiences into the future. It would not be unreasonable for Americans to fear a second round of inflation, one that would claw back whatever wage gains they currently enjoy. And it doesn’t help either that the US stock market, as measured by the SP500, reached current levels more than 30 months ago.

Two areas that are perhaps ripe for exploration, therefore, are the universe of prices that Americans don’t experience every day, and also, how the rise in long term interest rates have bled into everything—not just in credit card rates and mortgage rates, but in prices too.

Americans experienced inflation in real time, starting roughly two years ago, in daily prices like food, simple services, and energy. But there’s a large category of prices that come into the field of vision on a much longer cycle. For example, imagine that you have not had a major car repair in the past two years, but this summer had to have brake work done along with a major mileage trigger that addresses fluids, transmission, and other work that’s part of a major tune-up. Well, you would have been hit pretty hard with skyrocketing costs of labor and parts. This is similar to other long-cycle purchases or fees like insurance premiums, raised on an annual or semi-annual basis, and home repairs done by craftsmen. Just because you read a headline saying alot of Americans traveled to Europe the past two summers leaves out huge swaths of Americans who only travel once every 1-2 years, and for them, the new price levels seen in hotels, rental cars and airlines will have come as a shock. In other words, that longer-cycle round of price increases may not have landed on many Americans until last year, or earlier this year.

Interest rates are also potentially overlooked as a source of stress because, although national data shows a solid improvement in personal debt levels, the punishing rates on credit cards and mortgage rates will have also shown up for Americans more recently, starting slowly as 2022 began, and turning more severe coming into 2023. And the recent surge in long rates, just in the past three months, will deliver even more pain until it subsides.

When running Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign, James Carville famously said “it’s the economy, stupid.” The idea that Americans are no longer motivated by their economic condition is wild and improbable to say the least. The very worst, least competitive idea of all is that they’ve been duped by the media into thinking an economy that is great for them is, well akshually, bad for them. The bet you want to make is that Carville’s dictum, which contains an ancient truth, is still true. Otherwise one has to make a bet on a new, dystopian model of the political economy. That may chime with other dark views about the world, but is not likely to endure.

Further listening via YouTube: “We Are Unhappy,” by Will Oldham (Bonnie Prince Billy).

The ability of Americans to afford gasoline remains under pressure. The Gregor Letter has addressed this previously, pointing out that last summer, gasoline affordability nearly fell to the same extremes seen in the first half of 2008, when oil reached $150 a barrel and the average hourly wage purchased only 5 gallons of gasoline. Today, in the context of poor economic sentiment, if you are already annoyed at the general price level, well, a trip to the pump is likely to worsen your mood. Just briefly, it’s fair and reasonable to assert the purchasing power level that Americans find comfortable is when the average hourly wage buys at least 9 and preferably 10 gallons of gasoline. You can see how frequently, over the past 30 years, that the average wage has commanded this level of consumption by going to the fully interactive chart at FRED. Snapshot below:

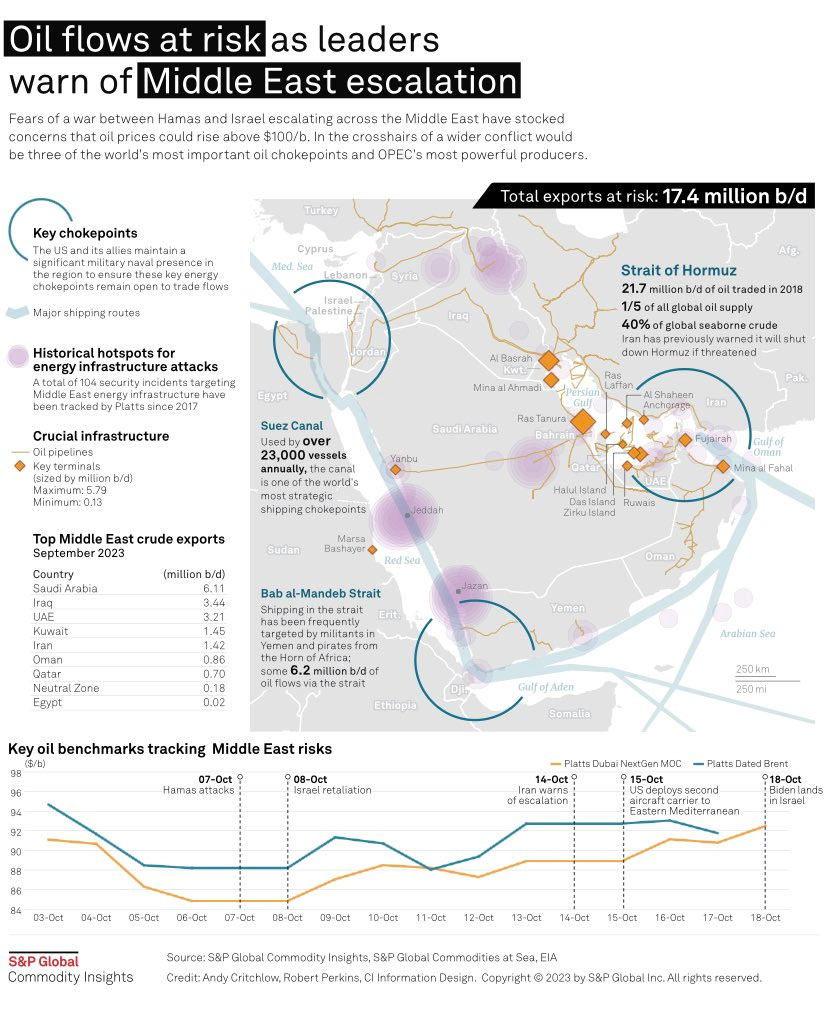

The temporary easing off last year’s extremes, when average hourly earnings purchased just 5.5 gallons of petrol, has unfortunately reversed this year and is worsening again. After a very brief hiatus in which the hourly wage bought nearly 9 gallons of gasoline in January, affordability has been heading back down, hitting 7.5 gallons September. October, after the Hamas attack on Israel, is going to see gasoline affordability worsen further.

Note: if you find this chart challenging, here’s a shortcut: the high points are when gasoline is super affordable, and the low points are when it’s insanely costly. Another note: do you remember how glum Americans were with the plodding rate of the economic recovery after the Great Recession? Look at the levels of gasoline affordability from roughly 2012-2015.

You may not like it, but higher real prices for gasoline are good for the climate and good for energy transition. Hey, I don’t make the rules. As The Gregor Letter has highlighted many times, successive years of OPEC cuts have supported oil prices at higher levels than they would otherwise be, and foolishly, OPEC has undertaken this policy as EV flood the world. In domains like California, where gasoline affordability is even worse, it’s no surprise that gasoline consumption finally fell off a twenty year plateau and EV sales are skyrocketing. Through the first half of this year, EV (plug-in) share of California vehicle sales is on track to reach 25%. The Golden State, ever the leading edge, is keeping pace with EV adoption superstars like China and the EU. And here’s a fun stat: through the first 7 months of 2023, California gasoline consumption is down 12.8% compared to the same period in 2019—the last “normal” year in the economy. Well, 2023 has mostly come into the normal realm, so that is an apt comparison. Here is what that looks like annualized:

The Gregor Letter downgraded its oil coverage starting earlier this year. What that means: apart from geo-political tail events which are not forecastable, oil is no longer a story worthy of constant attention. The base case outlook from The Gregor Letter is that global oil consumption peaked in 2019 above 100 million barrels a day, and consumption will oscillate around that level 1.00% - 1.50% in both directions as we move further into the decade. Because demand growth is now over, oil joins coal as a huge, ongoing problem for climate but is no longer a platform for economic growth. Electricity, as was forecasted years ago, is now that platform.

Importantly it must always be clarified that no demand crash is coming, and when global oil consumption does begin to decline, say around 2027, it will be very mild at the front end. From a climate perspective therefore, oil remains a huge, huge problem and will remain so for years to come because more rapid declines are some distance away. Oil investments and prices meanwhile have enjoyed a brief, two year reprieve from what was a terrible decade for oil and gas investors. This has predictably reset expectations and produced the usual and tedious refrain that the oil market is tight, and that the world is “clearly going to need a lot more oil.” Good luck with that.

Every time a geo-political event threatens to disturb oil markets, analysts return to their historical playbooks. Frankly, that’s tedious. The gesture is meant to bring gravitas to the discourse but when you start invoking the 1973 oil embargoes in 2023, you have probably lost the plot. The global topography of oil production has of course profoundly changed over the past half-century. Sure, Saudi remains the big player in OPEC but consumption has radically shifted to Asia. Western consumption, as measured by the entire OECD, peaked in 2005-2006.

If you believe for example that OPEC and the Middle-East are about to return to “crude diplomacy,” to hurt the US and western support for Israel, you have to ask yourself who gets hurt most? Not the US, that’s for sure. China, India, and the rest of Asia would be hammered hardest in any attempt by OPEC to resurrect the embargoes of old. No question, however, that such an action would concurrently damage the global economy. Which, as always, would lead directly to lower oil prices soon enough. In other words, OPEC winds up empty handed from any such action. But we must also remember that humans are only rational actors in part, and OPEC certainly could undertake an embargo that would damage themselves ultimately.

Chart currently making the rounds:

The IEA is back with their same, recent message about peak fossil demand. Great news. But peak is no longer the play. We’re on the hunt for declines now, and those are hard to find. In its most recent report, World Energy Outlook 2023, the Paris based agency again forecasts that fossil fuels peak before the year 2030, but it has improved its discussion greatly by pointing out this is not even close to achieving requisite emissions declines:

A legacy of the global energy crisis may be to usher in the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era: the momentum behind clean energy transitions is now sufficient for global demand for coal, oil and natural gas to all reach a high point before 2030 in the STEPS. The share of coal, oil and natural gas in global energy supply – stuck for decades around 80% – starts to edge downwards and reaches 73% in the STEPS by 2030. This is an important shift. However, if demand for these fossil fuels remains at a high level, as has been the case for coal in recent years, and as is the case in the STEPS projections for oil and gas, it is far from enough to reach global climate goals

Notice how the IEA cites coal, in exactly the right context. Background: global coal consumption peaked in 2013, fell gently for 6-7 years, then roared back to the previous highs in 2021. Indeed, this is the problem now with the concept of “peak” because it’s a useful term to mark general decarbonization progress, but is often an unhelpful term to the extent it suggests declines are coming. The Gregor Letter applauds the IEA for cleaning up its previous messaging from last month.

More good news: the IEA has seriously upped its chart game! The graphics in the latest report are absolutely gorgeous, and ingeniously designed. For example, you are probably familiar with case scenarios for future emissions declines: you know, in Stated Policies we see future declines based on current policies, or another pathway that’s more aggressive, like Net Zero, produces a different outcome. Usually these trajectories are put on a flat chart, often lacking precision. Now look at this:

There’s lots to love here. Especially the historical component, nicely married to the future projection. This graphic allows the reader to see 1. The climb in gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 emissions from 33 Gt in 2010 to the peak in 2022, at 37 Gt. 2. The slope of the emissions declines expected given the intensity level of each decarbonization pathway to 2050. 3. The expected surface temperature in the year 2100, depending on each pathway.

You will recall the previous discussion in The Gregor Letter, pointing out that the IEA had, in their last report, projected a slight increase in emissions from the 2022 baseline into the 2025-2027 period which is how a “decline” was created into the year 2030, and emissions at 35 Gt. In a way, this is noise. Yes, we want to hunt for declines. No, we don’t want to manufacture them or mischaracterize simply because of small wiggles in the baseline.

The general view of The Gregor Letter is that the declines will of course come, but they will come later, and probably be more pronounced on the downside. The bad news in that outlook: any declines between now and 2130 will be so slight as to be indistinguishable from an oscillation. We still won’t know for sure in 2030, in other words, if we are indeed on the emissions downslope. The good news in this outlook: the world is not going to follow that STEPS (business as usual) for the next 26 years, to 2050. The world is going to decarbonize far more rapidly, once we get going.

The tragedy: investment in more aggressive decarbonization in the short term, between now and 2030, would pay off big time, in a non-linear way if we could seize the day. But we are not being that aggressive.

The LA River Restoration project is coming along quite well. Progress on its companion effort, the LA River bike path project, is less clear. Your correspondent last week had a chance to catch up on both, photographing the same Atwater Village-Griffith Park area that was covered years ago at Atlantic Media’s Route 50. | see: A City Seeks to Create a Unique Asset in a 32-Mile River Bike Path | On the river project, a very significant change has taken place with the introduction of new plant life, grasses, and rock structures. Here are photos showing the new La Kretz Bridge for pedestrians, bikes, and horses—and the river that runs through it.

The twin projects are a very big deal, and apart from the ongoing hardening of NYC lowlands in the face of sea-level rise, they stand as the largest efforts of their kind in the US. The New York Times covered this just last year. Where the bike portion is going to run into a challenge, however, is in the middle section of the river that runs through downtown. It appears there has been no progress on this section in five years. And that’s not good, because in this portion of the river the available real estate tightens, and makes building a path far more challenging. The city’s goal to have this done by the 2028 Olympics looks doubtful, because so many real estate owners, including railbed, will have to be engaged in a negotiation. You can see that portion here, looking north from Vernon to downtown.

I was delighted to be a guest on the Clean Power Hour. You can enjoy my conversation with Tim Montague on YouTube.

—Gregor Macdonald