Wind Shift

Monday 9 February 2026

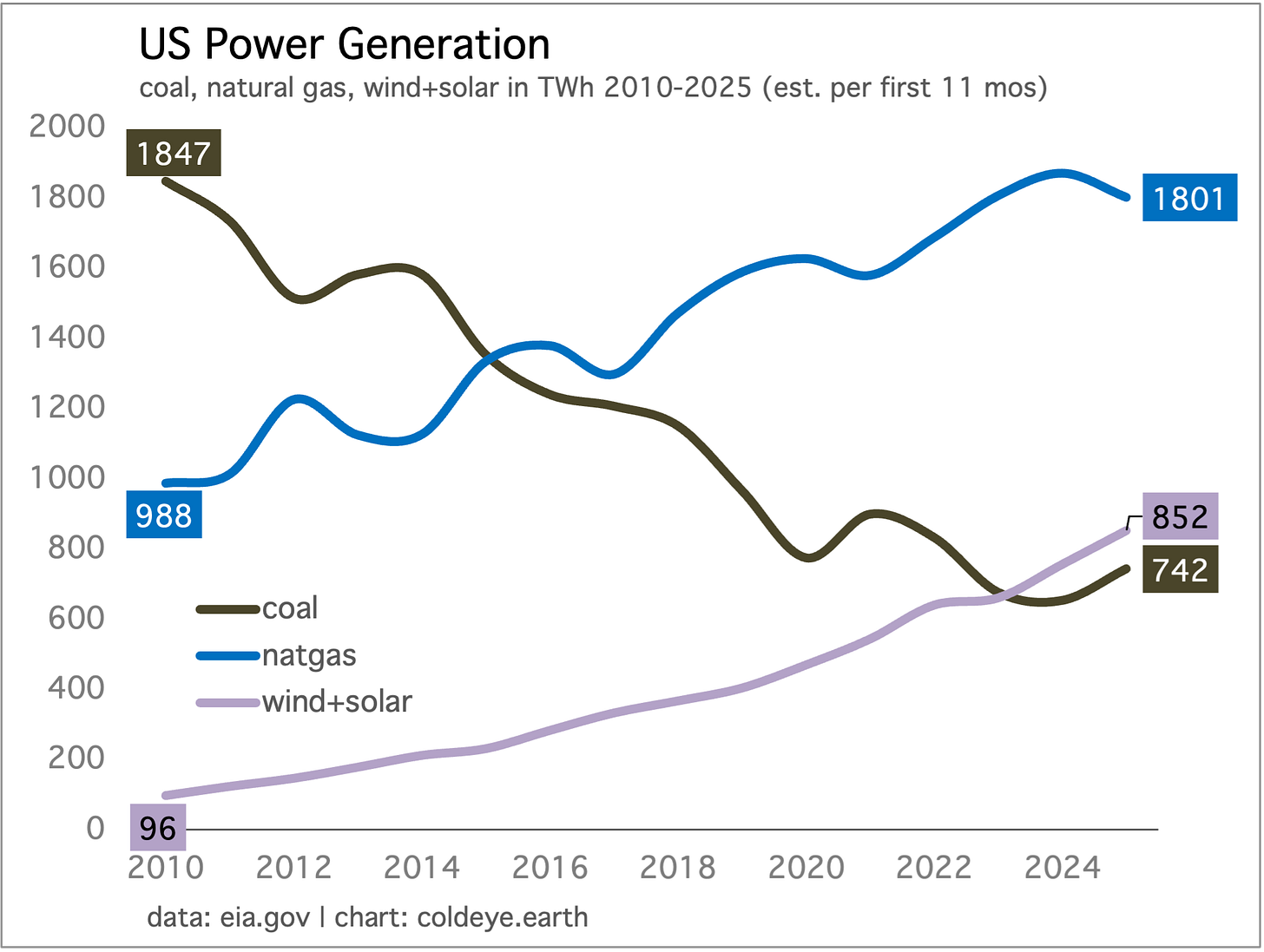

Coal-fired power generation popped higher in the U.S. last year. Coal consumed to make electricity soared by a fairly distressing 13.8%. But the spike represents no change to the overall trend of long-term decline. Since 2010, coal’s misfortune—a decline of roughly 1,000 TWh—has been exploited by natural gas and combined wind and solar. If we use a baseline of roughly 4,000 TWh to represent total U.S. generation over that time, coal in power has been more than cut in half. The misfortune will continue.

Meanwhile, natural gas and combined wind and solar have each advanced by about 800 TWh since 2010, not only covering coal’s losses but advancing further to cover total demand, which finally budged from that 4,000 TWh level and has now grown to 4,500 TWh per year.

Because natural gas has lower emissions than coal, there’s a common perception that dumping one for the other is an unqualified win. But that’s not true. Natural gas still produces strong emissions, and natural gas can also hitch its wagon to path dependency, eventually curbing (some of) the expected growth from combined wind and solar. Cold Eye Earth offers the following delineation to untangle the confusion:

• Operationally, combined wind and solar benefit greatly from having enough natural gas on the grid to support their intermittency. The engineering now available to modern, highly-calibrated natural gas power capacity is so advanced that grids can titrate the amount of gas power on the grid from hour to hour—stepping aside when wind and solar are going strong, and stepping back in when they weaken. So far, therefore, this fine-tuned ramping capability has worked perfectly with the rise of wind and solar. Up to some level of penetration therefore, we must allow that this flexible natural capacity has been necessary to help wind and solar spread their wings.

• Alas, once you go beyond that point then new natural gas capacity simply becomes another emissions problem to be solved, neutralizing a great portion of the improvement renewables secured in lowering emissions. Sure, you want to love and celebrate an extra 800 TWh of combined wind and solar, but doing so in the face of a fresh 800 TWh from natural gas is troubling. And unfortunately, this is the path that the U.S. has now taken. And no, wind and solar will not displace young, newly built natural gas capacity.

Facts change over time, morphing into new facts. It’s likely that many still believe the U.S. has an intractable coal problem, when in fact we now have a new problem in natural gas. This is the old “fighting the last war” phenomenon. No, coal hasn’t been zeroed out yet (as it has in the United Kingdom, for example), but directionally we are headed to the same destination. The U.S. has more than enough natural gas capacity in power, and we should be fighting further growth now with the same intensity and planning that was brought to bear on coal starting 20 years ago.

Long-term U.S. tariffs on Chinese solar panels raised prices and triggered a decline in solar industry employment. Those are the findings of a new 2026 study, “Beyond tariffs: A better approach to green industrial policy,” which examined these effects from the starting point of 2012. Unsurprisingly, the study’s broadest conclusion, that “overall human welfare declined,” derives from the simple fact that human health improves when emissions decline and worsens when emissions either rise, or hang around, not falling fast enough.

What’s delicious here is that it’s a perfect demonstration of the insights offered by the British economist David Ricardo more than 200 years ago. Even today, many people have trouble understanding what Ricardo saw: we live in a dynamic economy, not a zero-sum, static one, and tariffs affect far more than just import prices as they eventually shrink overall flows in targeted sectors, reducing earnings, total market size, and purchasing power of workers and consumers.

This is why Cold Eye Earth devoted significant time to Ricardo last year, when Trump returned to office with his caveman economic views. Here we used the example of bike frames and bike components, and the recognition that Japan makes the best components at the most competitive cost, and the U.S. tends to have an edge when making bike frames:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cold Eye Earth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.