Worlds Collide

Monday 15 November 2021

The tumultuous phase of energy transition has begun. The primary ongoing tension of this period will be found in the efficiency-seeking, deflationary impact of global electrification as it clashes with the flickering, inflationary pressures from a constrained fossil-fuel system—already choking on its own demise. The ongoing friction will produce competing prices, and competing theories. Most of all, short-term conditions will arise continually—feel all too real as they are embraced by crowds—only to recede, obliterated by a new set of conditions. Imagine, for example, a near-future Amazon enjoying a competitive cost advantage as it rides the wave of its 100,000 electric delivery vans while Comcast or other utilities, having come late to the scene and unable to source EV utility trucks, grapple with their dependency on gasoline. The business pages will struggle, as they are already, to choose a story that best captures these competing trends. It’s never easy, when worlds collide.

The deflationary impacts of transitioning away from combustion are well known to scientists and energy researchers. Oil Fall devotes a chapter to these accountings, undertaken by universities, institutes and governments over previous decades. Simply put, roughly half of the total fossil fuel consumed each year on the planet is lost to waste heat. Replacing combustion for the energy capturing devices of wind and solar, or propulsion and storage devices like batteries, triggers a clawback of these losses. Run that experiment continually and soon large tranches of wasted energy—also known as wasted capital, and wasted costs—will be removed from the system. Yes, new energy infrastructure has an upfront cost. But that cost is actually an investment that yields a return. In other words, there is a price but there is no cost in the current usage of the word, often meant to imply a loss. Why this hard fact has become politically contentious in the United States remains a mystery. Once upon a time American consumers enthusiastically paid up for pricier house insulation, more efficient car engines, and more expensive construction in their public buildings under the correct assumption that doing so would yield savings. But the US, unlike the rest of the OECD, has bogged itself down in recent years with a regressive posture towards any form of self-improvement. Just one example: spending bills (investment bills) are typically quoted in a single price tag that bundles up ten years of annual spending. But the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill provides only $120 billion per year of investment, while at the same time wowing the crowd with a headline figure. That’s not nearly enough for a country that’s stuck in a 50 year infrastructure deficit, with its associated losses to GDP and productivity.

What’s exciting to realize however is that the views of the general population will, as we move through time, converge with the facts. Warren Buffett once remarked that, in the short run, the stock market is a voting machine but in the long run it’s a weighing machine. In other words, given enough time, actual rather than perceived values will emerge. The same will be true for current perceptions about the high, up front cost of new energy and transportation infrastructure as we move through time, and actual values emerge more clearly in the future. Here is a thought: we may very well wind up with a surplus capital problem as energy transition frees up value and destroys waste in the system. This surplus capital is not likely to be distributed evenly in society, either. The vast majority of people will enjoy better air quality, and hopefully a cap on the rise of global temperatures. But energy transition is likely to generate enormous profits, and those profits will have their own secondary effects.

The current moment in the industrial economy understandably is reminiscent of previous transitions, as the world that existed just before the tumult is called upon to handle widespread, systemic change. Above is a photograph of New York in 1908, just as the Ford Model-T was being introduced, but before the mighty S curve of automobile adoption had gotten underway. The world you see here was built not by oil, but by coal. For the people of the 19th century (and early 20th), coal must have seemed quite efficient, quite powerful and, handily, quite available. Coal built ports, skyscrapers, railroads, and threw off so much surplus wealth that an upward swirling effect hovered over the century, which of course saw the long unfolding of the industrial revolution.

Something like that is about to happen to our world. Coal had a long tail of use and dependency that carried forward into the middle of the 20th century, even as oil soared. And oil will have a long tail of use and dependency in this century too. But oil, like renewables, started out from a small base and took at least a decade, if not two decades to reach the steep section of its adoption curve. The affordability of personal automobiles was just the beginning for oil’s upsweep, which was slower in the teens, and the 1920’s. What really propelled oil was the world’s emergence from the Great Depression (oil probably lost a decade in the 1930’s). WW2, and the post-war economic boom, put oil into overdrive. Look at that adoption curve!

Adoption of new technologies is disruptive and you can be sure that many coal-based machines, businesses, industrial processes, and jobs were made fallow by oil’s entrance. Creative destruction therefore is a fun concept for economists but less so for people whose lives are dependent on the status quo. For those whose jobs are on the leading edge of these changes today, anger and resentment towards new energy technology is going to deepen. Greenflation, for example, is the newest term to express these grievances. The embedded idea here, which you can discern pretty easily, holds that wind and solar and the platform change to EV is killing investment in fossil fuels while replacing them with far more expensive, newfangled tech that is unreliable.

There’s some truth among this general falsehood, but most of all greenflation tries to convert an ephemeral, quickly changing situation (surge of oil consumption in the wake of a global pandemic) into a long-term thesis. That’s not going to work out well, at all. If anything, the temporarily surging prices for oil, coal and natural gas are going to accelerate the rush to wind, solar, and EV. It’s happening already. Oil and natural gas prices especially, right now, are driving consumers in hoards towards EV globally, causing governments to rethink their energy choices, and propelling the electrification trend to an even higher speed. Indeed, these high prices for fossil fuels couldn’t come at a worse time—for fossil fuels. If you accept, for example, that OPEC is sitting on substantial spare capacity therefore, then OPEC is destroying its own self-interest and its future right here, right now. OPEC should instead flood the world with oil, driving it down to at least $40 a barrel if not lower. Doing so would ease the consumer urgency to switch to EV, would ease inflationary pressures (for a short while), and would probably not grow but help retain the customer base, for oil.

In the example of OPEC, however, we can understand better how the tumultuous phase of any transition becomes so choppy. As the new technology rises, incumbents freeze, like deer in the headlights. Their entire body of knowledge and experience has, at the historical turning point, set them up to fail even as they are sure of their expertise. If incumbents knew how to handle such transitions, then you would see an oil company like BP entirely eliminate its dividend, and announce that a majority of its cash flows and capex would be devoted to acquiring new energy infrastructure and related investments, and opportunities. But doing so would just be politically impossible, both within and outside the organization.

Since the industrial revolution, however, it has become more certain and predictable that new technologies will arise, and be adopted at increasingly fast rates into the economy. There’s a whole sub-discipline that studies these growth events and the 20th century was a veritable catalogue of rocket ship trajectories.

While most of these technologies improved the efficiencies of home life (refrigeration, clothing washers and dryers, and the telephone had almost universal upside with little if any downside) automobiles, television, and computers relegated former industries to the dustbin. And that was probably not much fun at all, especially if you raised horses, built buggies, ran radio networks, or worked as a book entry accountant. There is a massive installed base, therefore, of coal, natural gas, oil, pipelines, and associated automobile infrastructure that is already losing value and this erosion will intensify. Observe, for example, how incumbents like Ford, GM, and VW must both serve an existing customer base for ICE cars while also developing EV on a new platform. Surprisingly, on this challenge alone, Ford Motor Company which held back and let others step first into the EV game now looks ideally positioned for their decision to not bet the farm on EV just yet, but instead to have focused on electrifying their single most successful model, the F-150.

The most difficult challenge of this period will land on politicians, and politics. As the supply chain contracts for fossil fuels, the price spikes will worsen, and any incumbent—even the most clever—will take the blame. For example, there are solid indications right now that high gasoline and natural gas prices, along with consumer price inflation, are probably souring the public on the Biden Administration, even as job availability remains high. This is precisely the kind of volatile, mixed picture we can expect going forward. Worse, the tumult will likely interrupt energy transition itself, with time-outs caused by materials shortages, protests over lithium mining, climate action policies getting killed in legislatures, and economic growth scares.

Rivian went public and quickly zoomed to a $110 billion valuation, underscoring that in the US market it will be SUVs and trucks leading the EV wave. Ford rose strongly in the weeks before the initial public offering as the Detroit automaker holds a 10% stake in the start-up. Amazon owns a 20% stake, which is compelling on a number of levels. Rivian may wind up benefitting from that relationship through software, distribution, and other forms of tech assistance. Amazon meanwhile stands to benefit from the exclusivity of the partnership, as it looks to take an initial 100,000 EV delivery vans from the young automaker, with more to come.

Global EV sales are soaring this year, on pace to rise over 80% from 2020. Even more impressive is the market share growth. After notching a 2.6% share in 2019, and 4.3% share in 2020, EV will reach 7.2% of global sales this year. The analysis comes from BNEF, as reported in Utility Dive. According to the think tank, global EV sales will reach 5.6 million units in total, this year. It must be said, however, that China is very much leading the charge. The most recent data, just released this week, shows that yes—plug-in sales will now surely reach 3 million in the country. And industry analysts are talking about at least a 4 million if not a 4.5 million unit market next year. Consider this: China will surely be a 5 million unit market by 2023—matching this year’s global total. This opens up a question: how fast is EV market share moving in China? I conducted a twitter poll on that issue just this week. (Hit the tweet for results).

A tidal wave of lithium demand is coming and a severe supply shortage will reveal itself next year. That’s the conclusion from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, of London. Lithium prices, in Benchmark’s view, could rise from just $6,100 in November of last year, and $30,000 currently, to over $40,000 in 2022. One description of the shortage comes from Rio Tinto, which is cleverly extracting lithium from above ground waste tailings in California and is also going ahead with a lithium development project in Serbia, called Jadar. According to Rio’s head of economics, the world would need 60 projects the size of Jadar to fill the supply gap over the next several decades.

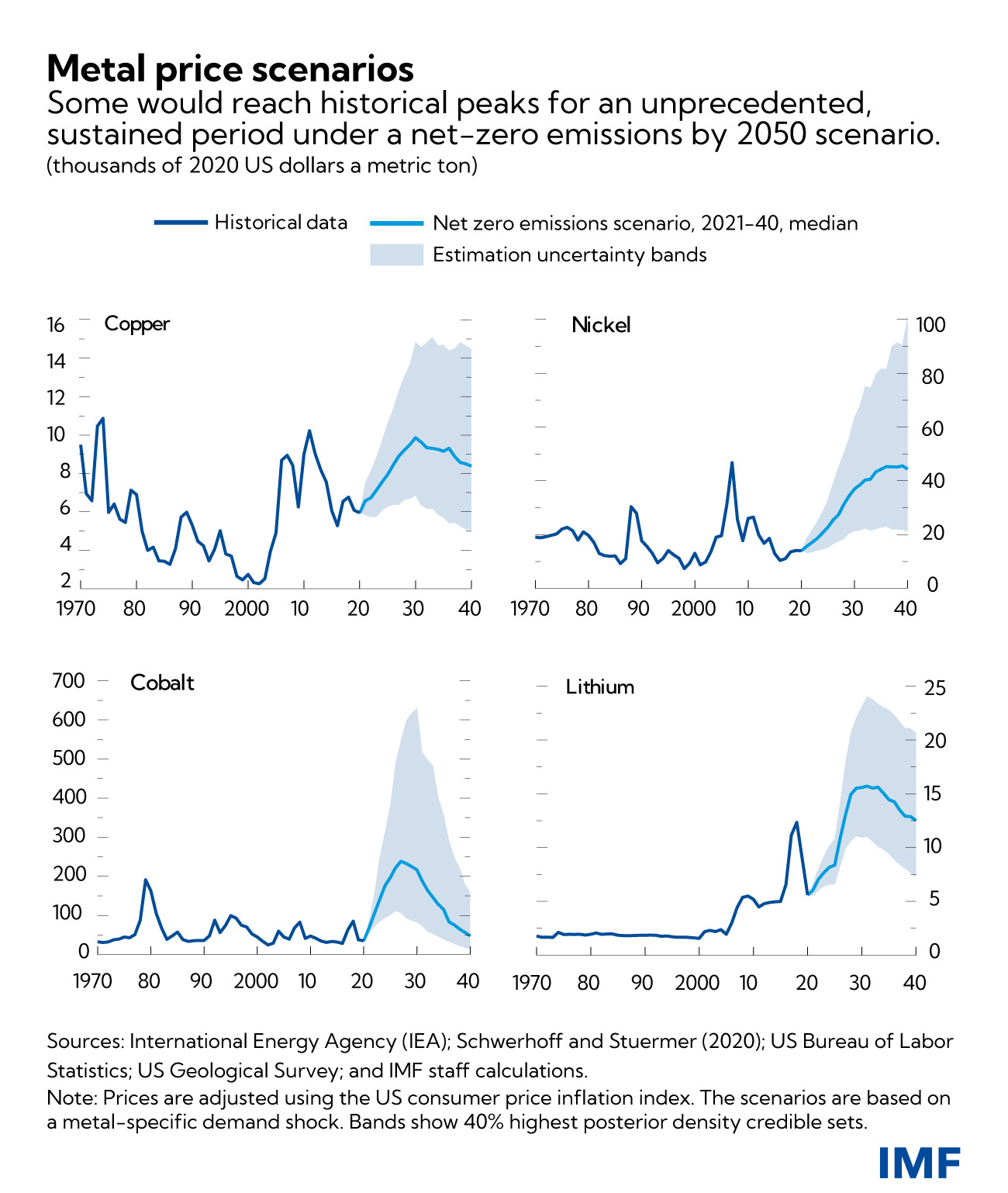

Lithium is not the only energy transition resource heading into a pressured supply situation. World demand for copper, nickel, and cobalt in a Net Zero emissions scenario will rise twofold, fourfold, and sixfold respectively, according to a US-EU research team. Their paper, Metals may become the new oil in net-zero emissions scenario, published at Vox.eu touches on a theme also made by London’s Benchmark: the rate at which battery factories or new wind and solar equipment can be manufactured is far faster than the rate at which metal mines can be developed to the point of production. This temporal mismatch will be chronic enough to maintain a constant, upward pressure on prices. The IMF also acted as host to this paper, and in a variation on the theme, published its findings under a slightly different title: Soaring Metal Prices May Delay Energy Transition. Here’s the key graphic from that post:

Perhaps the most arresting conclusion from this paper, however, is that the total volume and prices paid for these four key metals could rival the value commanded by the oil market, over the same period. That is bracing.

In the net zero emissions scenario, the demand boom could lead to a more than fourfold increase in the value of metals production – totaling $13 trillion accumulated over the next two decades for the four metals alone. This could rival the estimated value of oil production in a net zero emissions scenario over that same period (see Table 1). This would make the four metals macro-relevant for inflation, trade, and output, and provide significant windfalls to commodity producers.

Inflation is going to become a political problem, even if you believe it will eventually subside. The Biden administration and other incumbents are probably going to face a successive round of partisan beatings until consumer prices and energy prices ease. Last week’s CPI report kind of blew the lid off the ongoing discourse over whether inflation would be transitory, or not. Paul Krugman took to Twitter to say that he had been wrong. Talk radio exploded with inflation coverage; which, when you think about it, is kind of wonky—for talk radio.

The current inflation situation is a gumbo mix of competing factors, most of which are hard to disaggregate. There are problems at ports, problems with supply chains more generally, and still unsolved mysteries around whether older workers have retired for good, or whether they and other workers will eventually return to the labor market. Layer in seasonal pressures on oil prices and natural gas prices, and the lagging effects of a global industrial shut-down just last year, and it can be hard to get one’s bearings.

One plausible scenario: the disinflationary forces that have been at work for nearly 40 years are still with us, and are ready to make their return. But inflationary pressures may hang around long enough to upend politics, markets, and policy for as much as another year. And then, just as those who were initially in the transitory camp (Team Transitory) throw in the towel and capitulate to a new regime of higher prices, the supertrend of disinflation will reassert itself.

—Gregor Macdonald

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, just hit the picture below.