Boom Boom

Monday 5 February 2024

The economic policies of the current administration have solved longstanding problems in the US economy that both liberals and conservatives have complained about for decades. Malinvestment, stock market bubbles, artificially low interest rates, a Federal Reserve overly involved in the economy, too much foreign aid while America is neglected, the hollowing out of US manufacturing, and long forgotten regions that missed out on economic expansion—these were the stock ideas flogged by everyone from think-tanks to politicians over decades.

True to form, Americans like to both complain about conditions, and then complain all over again about the solutions. This was true when the Reagan administration made long overdue changes to the US regulatory environment, and during the Clinton administration when tackling deficits really did have a comprehensive effect on interest rates—making the pursuit of left-leaning policies so much easier. Liberals complained bitterly at the outset of both those administrations for going too far right, but now the shoe is on the other foot. Sorry, but it is actually quite hilarious to see conservatives complaining about the successful effort to invest in America! We literally have boom conditions unfolding across long abandoned regions, red states in particular, as energy-tech investments blossom with jobs from West Virginia to South Carolina.

There is almost no need to post links here to jobs numbers, soaring manufacturing investment, and indications that we might also be on the cusp of a true advance in productivity. This has all been unfolding since last year and the stock market is responding by making successive new, all time highs. Europeans would kill for such conditions. But when it comes to pampered, ideological Americans you simply have to stay patient, and let them work through their tedious, narcissistic issues.

The US economy is booming, the nature of the boom is far more balanced than in the past two decades, and it all derives from sparking investment in a country long starved of attention to both infrastructure and domestic output. You can celebrate it now, or you can celebrate it later, but you will wind up celebrating it eventually.

Cold Eye Earth thanks its readership for its patience and understanding during the publishing blackout last month. We went 9 days without power, 6 days without water, 5 days without internet, and to top things off, there was a fire in an adjacent building. Like the script to a good horror flick however, after everything went back to normal, the internet and hot water went out for another two day stint. Eesh. I gave up at that point and went to a hotel for WiFi and a bath, after leaning on friends for both for two weeks.

A brief thought about systems: watching the Portland Fire Department try to fight a fire during high winds, and ice covered surfaces, was an occasion to think about the problem of cascading failure. And yet, these hurdles are well known to the fire department, as my conversations revealed. Tell me if you’ve heard this before: every person who’s life or property was either directly or indirectly affected by a fire comes away with a kind of mind-blown appreciation for fire-fighting professionals. The Portland Fire Department had a very difficult month in January. They are heroes.

Coal in the US power sector has fallen steeply, and will soon be overtaken by combined wind and solar. The US has been retiring coal-fired powerplants for over a decade, and last year’s decline was particularly strong when coal power in TWh terms fell over 18%. Meanwhile, electricity from combined wind and solar has been growing quickly in the US system, and is now about to crossover.

The data for 2023 isn’t quite complete; and we await the numbers for both December, and revisions. Perhaps coal strengthened at year end, and perhaps solar fell off, while wind power advanced. The EIA like any other data gathering organization also tends to revise, and in recent years, those revisions have often yielded a small, upward change of around 1.00% in wind and solar. But, this is all inconsequential and statistically unimportant. Combined wind and solar will provide more power to the United States than coal—starting right now—and the crossover, somewhere around 670 terawatt hours, will be permanent.

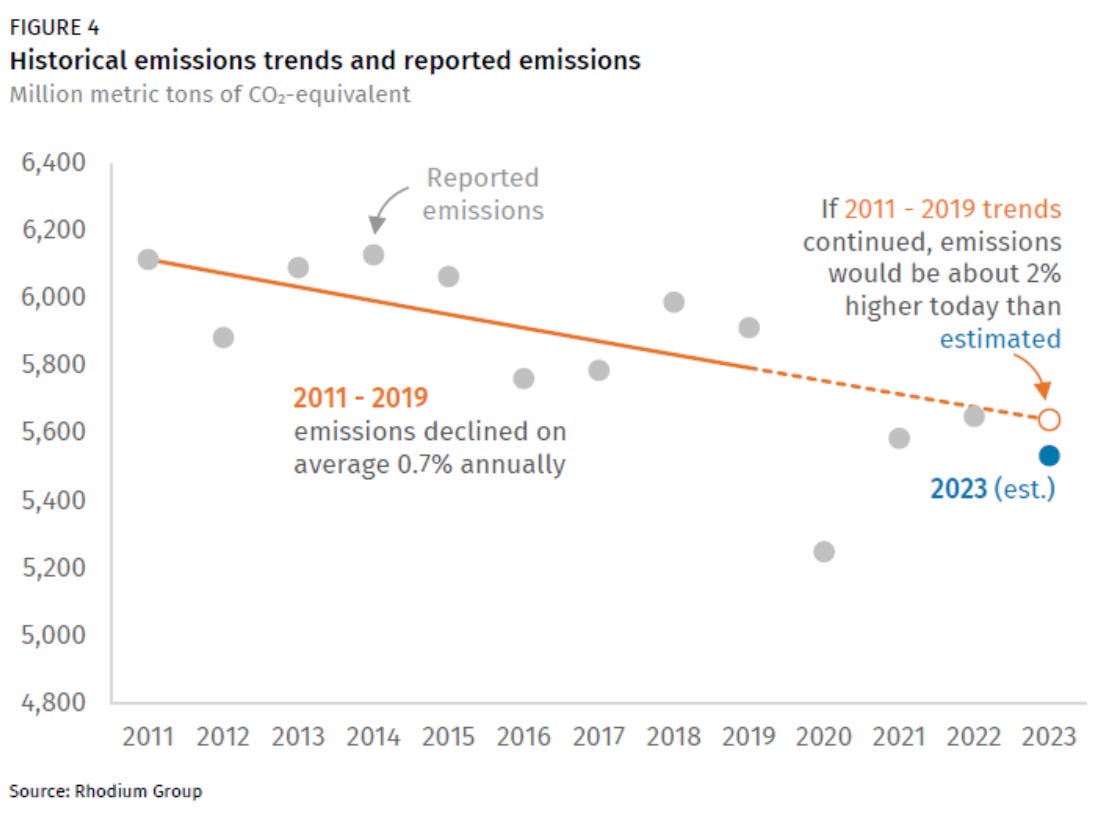

Progress in emissions reduction has slowed greatly in the US, and it’s not helpful to say otherwise. Over the years there’s been a fair amount of armchair social-psychology in the climate community, with many theorizing that bad news is dispiriting to progress and good news catalyzes further momentum. And yet, there’s no evidence for it. To illustrate further that this armchair speculation is nothing but institution, there are those who’ve argued the opposite: that bad news is motivating, and good news promotes laziness. The only reasonable approach therefore is to be as accurate as possible.

Right now, the most accurate description of US emissions is that, starting with the rounded peak in 2005-2007, the US made extremely encouraging reductions that crashed into a wall starting in 2018. In that ten year period from 2007-2017, US emissions fell a total of 14.7% from 6016 to 5132 million tonnes, or 1.47% per year on average. (note: emissions like most other data series are anything but average, year to year, and are quite volatile). Emissions then started rising again. In both 2018 and 2019, emissions were higher than in 2017. Then came the spectacular bust in global energy consumption during 2020’s pandemic, and it was normal for emissions to recover in 2021-2023.

However, even inclusive of the outlier year of 2020, which pulled the annual average down, emissions in the 2017-2023 period fell 6.41%, for an average of 1.07% over those six years. That is meaningfully slower progress than the prior measured period. And, readers of Cold Eye Earth already know the reason: soaring emissions from rising natural gas consumption, and transport sector emissions that refuse to decline.

This should not be surprising either. Many journalists and scientists who follow emissions began to point out five years ago that the harvesting of emissions declines in the United States had thrived on big, early, and easy wins. The opportunity set to harvest further emissions declines, therefore, would soon dry up. The prediction has come to pass. You simply cannot achieve sustained emissions reductions just by attacking coal with wind and solar, for example, because natural gas is taking up so much share of the coal gap. Emissions from natural gas in the power sector have risen by roughly 7.00% in each of the past two years (2022 and 2023). Meanwhile, oil in transport suffers no policy effort at all in the US, and marches forward along an oscillating, twenty year plateau.

Both natural gas and petroleum consumption should now be regarded as outright policy failures in the United States.

In a recent report by the Rhodium Group, however, it was suggested that progress on emissions was potentially accelerating in the US. To support this conclusion, Rhodium drew a more forgiving baseline of US emissions, one that starts in 2011 rather than at the actual peak, which occurred over three years from 2005-2007. Curiously, Rhodium cites this same peak in its report, but again, draws a baseline that specifically does not include it, choosing instead an eight year time period from 2011-2019. By using that timeframe, it supports the conclusion that there hasn’t been a break in the decline rate—that there hasn’t been a slowing of emissions progress.

It should be pointed out, however, that Rhodium appears to be using more inclusive emissions measures, that go beyond energy related emissions. And perhaps they see something in that data set. But Cold Eye Earth rejects the above chart: its chosen baseline is not defensible, does not have any reasoning behind it, and produces a hopeful conclusion which is not warranted. Had Rhodium started the baseline at the actual peak of US emissions, their conclusion would evaporate.

Indeed, US emissions progress should be accelerating by now. The scaling up of wind and solar and batteries is going extremely well. But instead of transitioning from a ten year emissions decline rate of 1.50% per year to 1.00% per year, we should now be seeing a transition to a 2.00% decline per year. To be sure, on the current course, 2023 emissions will have dropped by 2.00%. Encouraging. But alas, one year does not make a trend.

The Biden administration has upended expectations by placing a pause on the future expansion of US LNG export capacity. The decision has created unusual faultiness within various communities, from climate folks, to energy security think-tanks, and of course the fossil fuel industry. Typically, in situations such as these, everyone reacts to the headline first, before actually looking at the details. In this case, that’s a bigger mistake than usual because US LNG export capacity is going to at least double, if not triple, before the pause actually kicks in. That’s right. Multiple projects will go forward well before the pause kicks in. This chart from Carbon Brief, for example, gives a general view that under construction projects nearly match the operating capacity.

Myriad charts are floating about this week but, safe to say, some portion of the proposed proposed projects will go forward because the pause is on pending decisions, and in the universe of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) there is a gap between “under construction” and “proposed” for approved projects. To this point, see FERC’s own category of “Approved, Not Under Construction.” Needless to say, the pipeline is challenging to fully quantify because all sorts of uncertainties can play out before a project actually gets built, both on the regulatory side and the commercial side.

Perhaps a better way to view the situation is through the lens of all LNG projects that will surely be built globally. Carbon Brief once again pulls the right chart here, this time from the IEA. What it suggests is that the world is presently on course to build a massive amount of LNG export capacity, and it’s probably too much.

Cold Eye Earth takes the following position on this policy development:

Supply side curbs are almost never an effective way to fight climate change. However, there’s an obvious flaw in the argument of those who claim to be on the side of fighting emissions, but who also believe expanding US LNG exports would help fight coal in the rest of the world. As we’ve learned here in the US, trading coal for natural gas in the power sector does get you a one-time step down in emissions, but then the new natural gas fleet grows and starts expanding emissions. We need the rest of the world to trade in its coal power for wind, solar, and batteries—with just some natural gas on the side.

That smaller quantity of natural gas is required to support renewables growth. And when we look at modeling of countries like Germany, who have goals to entirely decarbonize, we find that they still make room in the far future for at least 10% natural gas in the powergrid, just for this reason. Accordingly, if the US were to build a gargantuan amount of LNG export capacity—rather than the simply very large amount of capacity it is set to build anyway—this could meaningfully lower the price of natural gas globally, providing too much competition for renewables. Curbing exported supply in the future is not a pretty method, but in this case it may be necessary.

—Gregor Macdonald