Edge State

Tuesday 8 October 2019

California gasoline consumption is falling again, and frankly it looks recessionary. Through the first 6 months of 2019 California’s taxable gasoline sales fell by 2.32%, a rate of decline not seen since the last US recession. This is the second year petrol demand has fallen since the peak of 2017. Is California sending a signal?

While it would be exciting (and handy) to ascribe the steep decline in petrol demand to the adoption of electric vehicles, the better explanation is to be found in the total decline of California’s car market, now down 5.24% through the first half of 2019. To illustrate, California sold 2.001 million passenger vehicles in 2018, but this year is on course to sell just 1.897 million vehicles—a decline of over 100,000 units.

Meanwhile, total plug-in sales are far weaker this year, and will at best reach 190,000 units. To be sure, on an absolute basis, that’s still quite impressive and there is no question that EV are killing future growth of petrol in California. As The Gregor Letter has pointed out, sales of internal combustion engine vehicles have absolutely peaked in the Golden State (2.013 million ICE units in 2016) and will never make it back to that peak. Period.

However, the growth rate of EV sales this year is far weaker than years prior, on course to be up just 20% to 190,000 units from 2018’s 157,000 units. EV growth in California jumped 60% in 2018, and 30% in 2017, by comparison. There is also considerable risk that when the final sales data completes for this year, we may see that projected 20% growth rate undercut. Nationally, EV sales are merely flat this year compared to 2018, and the total market decline for cars generally in California is a warning that Q4 sales—often relied on to finish strong—may instead disappoint.

As you can see in the gasoline chart, last year’s demand decline from the 2016 peak of 15.58 billion gallons was also a warning—though at 15.34 billion gallons, represented just a 1.54% decline. (Total car market sales fell just 2.23% last year). This year however, gasoline sales are on course to reach just 14.98 billion gallons, a full 580 million gallons less than the 2017 peak for a total two year decline (projected) of 3.80%.

So why should we favor weakening economic conditions over EV adoption as the best explanation for the declines? Easy. Total plug-ins on California roads make for a fleet of about 600,000 vehicles now, out of a total state vehicle fleet 35,700,000. So it’s the delta in the 2019 sales of ICE vehicles, declining at 100,000 units, and less so the delta in the sales of EV, increasing by 33,000 units, that indicates the problem developing in California. Moreover, vehicle sales declines of over 5% are typically associated with fewer miles driven.

Perhaps we will learn, at a later date, that immigration flows into and out of California started to turn this year. Additionally, other explanatory factors may eventually include a new round of workers telecommuting, or using public transport. Regardless, the general projection laid out last year in the Oil Fall series is essentially coming true: 1. The total car market is in decline, and heading for a low sometime in the year 2020. 2. The decline is pulling petrol demand growth downward either to a flatline, or to negative levels. 3. ICE cars will have already lost market share to EV before the 2020 bottom, and will have ceded most if not all of the growth to EV during this period. 4. When the car market recovers in 2020—either early in the year but most likely later in the year—it will be too late for ICE, and all car market growth will continue to swing towards EV. 5. The set of policy measures which California started rolling out in 2017—everything from higher petrol taxes, to surcharges on ICE cars and continued support of EV sales—will also start to hit petrol demand. Indeed, in the summer of 2017 I reported for Atlantic Media that California was so confident, in its modeling, that petrol demand growth could be halted through policy that the state was preparing for a long period of declining tax revenues, from gasoline sales. And so, here we are.

To conclude, declining ICE sales, steady EV sales, and petrol taxes are all contributing to the decline of California petrol demand. But it takes something bigger moving through the system to put together a two year decline like this and, as America’s edge economy, California is more likely telling you to take the recent weakening of US macro data seriously.

The public continues to be mystified, doubtful really, that we can run all the electric cars easily on new electricity from clean energy. I ran these numbers in the Oil Fall series for the United States, China, and California so let’s run them again, now that we have the full 2018 and partial 2019 data.

To see how this calculation works, we take the year-over-year change in new electricity generation in California from wind and solar alone, and compare it to the projected demand from new on-road plug-in vehicles. For example, California generated 47.78 TWh (terawatt hours) from wind and solar in 2017, and 53.64 TWh from wind and solar in 2018, thus growing clean generation by 5.96 TWh in 2018. But also in 2018, California put a fresh 157,659 plug-ins on the road which at best represented a new demand of 0.6306 TWh of electricity.

Why do I say: at best? Because nearly 40% of those vehicles were PHEV (plug-in hybrid electric vehicles). And yet, I have imputed to them the same annual demand for electricity as the pure electrics in order to be overly safe in the calculation, which multiplies each new plug-in by a standard 4000 kWh (kilowatt hours). Ergo: 157,659 plug-ins*4000 kWh = 630,636,000 kWh or 0.6306 TWh.

In 2018 therefore, California could have put not just 157,659 fresh EV on the road, but nearly 1.5 million new EV on the road and this new annual demand would have been covered entirely by the growth in new electricity from wind and solar. While the growth rate of new wind and solar generation has eased a bit (both 2018 and 2019 saw lower marginal growth than 2017) the fact remains that this new supply of clean electricity dwarfs new demand from EV.

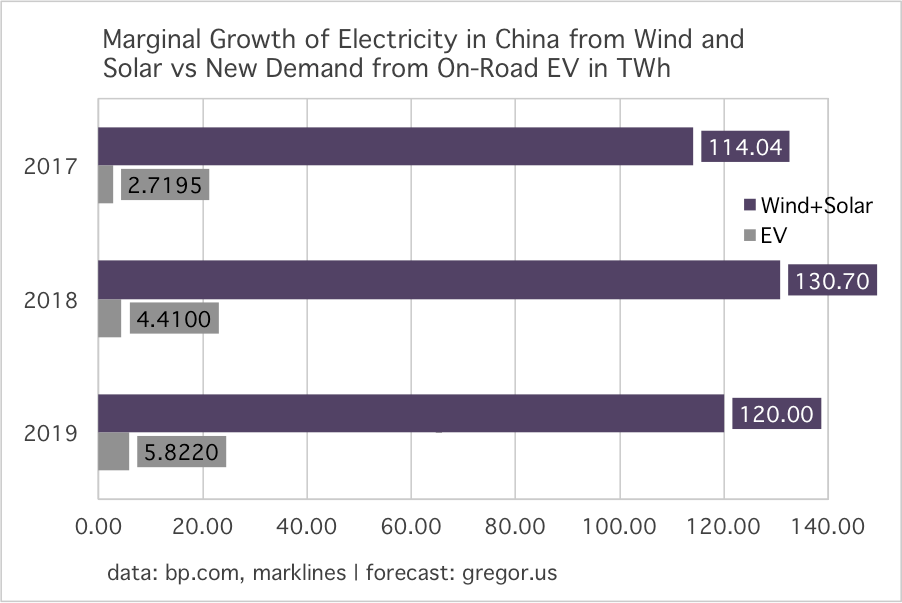

In China the dwarfing is even more spectacular. Just as you’d expect, right? What’s singularly impressive here is that China put 770,000 EV on the road in 2017, 1.26 million EV on the road last year, and is on course to put about 1.66 million units on the road this year. In China, the miles driven are far, far, fewer than in the west. And yet, to obtain the calculations below, I’ve imputed 3500 kWh of annual electricity demand from each new on-road EV in China. This is almost certainly too much, but it makes the comparison safe. And yet, even with this overly generous estimate of demand, China created nearly 30X more supply from just wind and solar last year.

There is no doubt that when the belly of the global EV adoption curve starts taking shape, many domains will have to step-up their wind and solar game. Otherwise the currently common, and wrong, assumption that “EV are just running on coal” will have some merit (more likely, it will be natural gas in many domains that gets the call). But wind and solar, like EV, are poised to become the go-to marginal supply in most domains now, whether through retirements of existing coal in western economies like the US, or through the new buildout of generation in the Non-OECD.

California gasoline prices are currently hitting five year highs. Through a combination of refinery issues and stepped up petrol taxes and fees the statewide gasoline average rose above $4.00 per gallon in October. Meanwhile, the model forecasting future petrol revenues, created by the state several years ago, is unfolding now as a surge of income washes into Sacramento (see: page 173 of the Governor’s budget summary). This interrupts a long, flat period of state revenues from petrol taxes. But, the surge won’t last. As the total ICE fleet peaks, and all growth swings to EV, the state will have to find revenue growth from a source other than the gas pump.

A deeper look inside California EV sales shows the market is swinging heavily now, away from plug-in hybrids, towards pure electrics (BEV). Without question, rising sales of the Tesla Model 3 account for much of this swing. For example, the PHEV share of EV sales in 2018 stood at 39.8%, but this year that share has fallen to 28.6%, according to data from CNCDA. My comment: the Chevrolet Volt, an extremely popular PHEV with 50 miles of electric range, has now been taken off the market. Accordingly, while consumers in the US market can still choose from myriad PHEV models, most of these top out around 25 miles of electric range. Such low, electric capability no longer looks appealing, especially at current price points. There’s not much you can do with 15 to 25 miles of electric range; many PHEV’s don’t allow you to run in electric-only mode, and this electric assist functions mainly as a way to moderately boost overall energy mileage efficiency. The long-term future for PHEVs is probably not that great.

The Trump administration’s move to open up lands in California’s central coast for oil drilling is pointless. By the time any oil and gas flows from these currently pending leases (there will be additional legal hurdles to face for operators) it’s not clear such extraction will be economic. The US is already oversupplied with oil, and increasingly exports surpluses through finished petroleum products to the rest of the world. The regulatory signaling action from the administration is not unlike it’s attempt to wrest control of emissions policy from Sacramento. And so the prospect that these federal challenges actually take hold is highly unlikely.

—Gregor Macdonald, editor of The Gregor Letter, and Gregor.us

The Gregor Letter is a companion to TerraJoule Publishing, whose current release is Oil Fall. If you've not had a chance to read the Oil Fall series, the single title just published in December and you are strongly encouraged to read it. Just hit the picture below.