Election Risk

Monday 14 October 2024

Global solar manufacturing remains in overcapacity, and is expected to reach a level that’s twice the size of annual output, by the end of this year. While this makes for exceedingly challenging conditions for producers, overall it’s terrific news for solar growth as prices are once again pulled lower—significantly lower. According to the IEA, in its just released renewables report, global capacity will grow to 1100 GW, and has already resulted in a halving of PV panel prices. Importantly, the IEA notes this glut is now triggering cancellations of new manufacturing capacity—and frankly, that’s fine. New, fast growing technologies typically oscillate between tight supply and oversupply as upwardly volatile growth cannot easily be matched with finely calibrated planning. Indeed, that capacity grew quickly and actually topped out is a great sign: it means the world is justifiably eager to capture future solar demand, doesn’t want to miss out, and sees an even bigger annual market to come. Best of all, if demand spikes, the capacity is ready.

Forecasters expect global solar additions to reach 550-600 GW this year. And we are likely to see solar continue to spread more robustly now across the Non-OECD, as prices fall. Cold Eye Earth has previously made the point that later adopters (typically countries that are not as rich as the early adopters) will eventually wind up as fuller beneficiaries of the manufacturing learning rate. So, while China will continue to be the top global adopter, we should anticipate now that solar will spread even more quickly through Asia and Africa. A good proxy for this anticipated growth among the laggards of solar is India, where per capita deployment so far has been disappointing. Right now, the economic conditions are stellar for India to massively increase solar. Let’s hope that happens.

Wind and solar are having a very good year in the United States. Together, they are on course to reach 17% of total US generation in 2024. Even more impressive is that wind and solar are easily keeping up with total system growth, which is currently set to reach 4.4% this year. How fast is US wind and solar growing? The two energy sources together accounted for not quite 10% of US power in 2019, just five years ago. They will likely reach 20% share in the next two years.

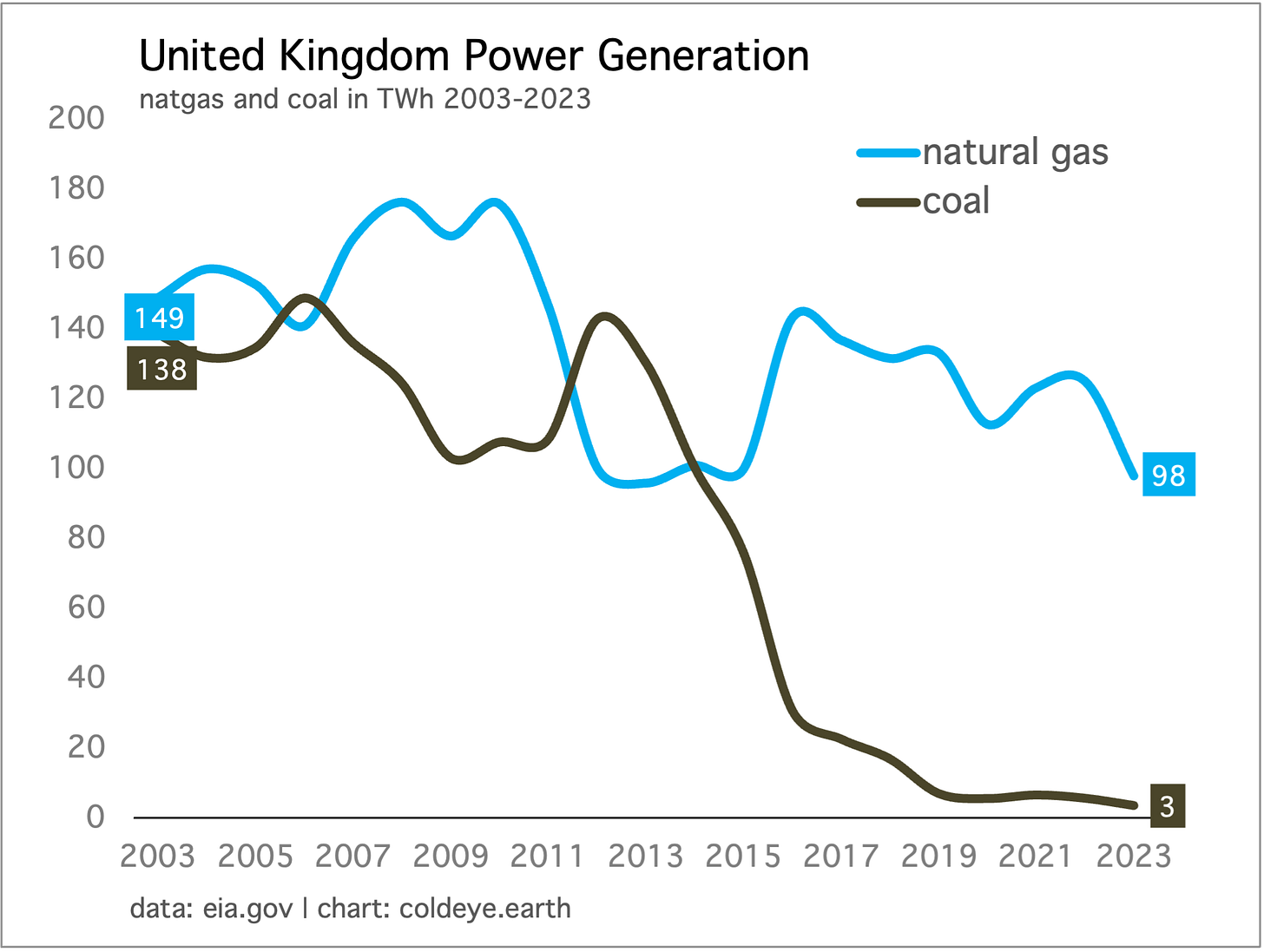

The United Kingdom has zeroed out coal, in power generation. Impressively, this cleaning of the grid was accomplished without adding more natural gas, thus locking in all the emissions gains from the effort. How did they do it? Wind power. Offshore wind power, especially. In the chart below, you can see the final, remaining coal presence that hung around in 2003, providing just 3 TWh of power to the UK Grid. As of last month however, with the closing of the country’s last coal plant, that leftover is now gone.

Notice however that power generation from natural gas has been cut by 30% if one uses 2003 as the baseline. Yes, for a short period after 2015, natural gas in UK power rose again, but that setback ended shortly thereafter and gas in power resumed its decline. This outcome matters to the larger conversation about how emissions in power can be lowered through myriad strategies, because a number of observers have lapsed into thinking that natural gas is key to lowering coal emissions. The UK showed that is not the case at all.

Natural gas is going to play a crucial role in the transition to renewables, but not as a baseload solution. Because gas can be paired with highly-efficient turbines that can act as grid balancers and back-up, it’s almost a certainty that a highly renewable grid of the future will have some natural gas (and nuclear) as key parts of the puzzle. In a June issue, Portfolio Nuclear, Cold Eye Earth offered up a plausible end-state in which natural gas provides 10% of global power. Note: it has long been the position of Cold Eye Earth that a successful energy transition, in electricity, will be reached when renewables make up the bulk of generation with small roles for natgas, hydro, and nuclear. The 100% renewable goal is not necessary.

Unfortunately, the United States unlike the United Kingdom has built far too much new natural gas during the great coal retirement cycle. This means that every gain made by closing a coal plant has been diluted by the opening of a new natural gas plant. Again, the US will absolutely need natural gas in the future to help balance a grid that is highly dominated by renewables. This principle is also going to be true at the local or commercial level, where regional or commercial grids are also made more robust by natural gas capability. But the US has seriously degraded the collective effort to close coal power—which is not an easy thing to do—by replacing too much of that capacity with fresh natural gas. The chart tells the tale:

The US is to be congratulated for taking coal power down from 1847 TWh to 829 TWh from 2010 through last year, and, for growing combined wind and solar from 96 TWh to 639 TWh. As previously stated, wind and solar growth in the US is quite good, and that line will be going higher this year, next, and the years thereafter. The problem is that the 1000 TWh of coal we cut, and the 500+ TWh of wind and solar we added, is being diluted—quite seriously diluted—by the growth of 700 TWh of natural gas.

No one argues that natural gas produces fewer emissions than coal. If you replaced 100% of your coal fleet with a new natural gas fleet, you will have lowered emissions. The problem is that this is a one-off gain. Inexorably, a young natural-gas fleet exerts path dependency, and it also becomes capacity that can run more hours, if necessary, to handle demand. This is why you do not want to lapse into making the general formulation that “we need natural gas to lower coal emissions.” No. Let’s make this plain: the closing of coal plants lowers emissions, and the deployment of wind, solar, and storage in substitution preserves those lower emissions. Increased use of NG in the power sector does not lower emissions.

Only in a world which contains no economically affordable solution to the closing of coal-power other than the building of NG-power can we say that NG is the thing that helps us lower emissions. We do not live in that world, and we haven't for a while.

Rhetoric from the Trump campaign has been more harsh than usual on the topic of energy transition, energy policy, and legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act. While Cold Eye Earth continues to forecast that the job-creating effects of the IRA in red states places a natural brake on any federal level efforts to undermine that development, we need to consider that rhetoric can also have a dampening effect on business outlook, and the plans industry makes.

This is particularly salient as the prediction markets and polling have tightened the past few weeks, indicating that neither candidate has an edge, because the bulk of the swing-state polling is well inside the margin of error. That shift, in which Harris seemed to be holding on to an edge in many swing states, has now slid backwards in the shorter-term polling. On one level, this is just noise. But on another level, it raises the uncertainty over the election’s outcome to a higher level because it’s nigh impossible to make any useful prediction when the race is in such a standoff.

For those of you outside the country, here are some current points of conversation that have recently come to the forefront:

• The historical disparity between the national vote and the electoral college result—which has disadvantaged Democrats—may be receding this year, as we are getting indications that some voters in deep blue states like California and New York are shifting to the right, while some voters in deep red states like Texas or Ohio are shifting left. These shifts are of course too small to put Texas or Ohio into the hands of Democrats or California or New York into the GOP column. But if those shifts play out as expected, then the historical phenomenon by which piles and piles of Democratic votes build up uselessly in blue states may ease. Equally, excess Republican votes could wind up just as useless in a state like Florida, whose right-leaning population has grown strongly since 2020. Some of the polling done by the New York Times, for example, has notably raised this possibility.

• Harris seems to be doing even better than Biden with white voters with a college degree, but there are legitimate concerns that she is doing worse with young voters of color. This was a theme sounded out by Barack Obama over the weekend when he gave a fiery speech in Pittsburgh, PA that not only made points about Trump but called upon Black men to step up and vote for Harris. Understandably, some have read this as a sign that the campaign is nervous. Well, that in itself is not notable: James Carville for example recently said that the only way to win elections is to stay terrified.

• Trump’s vote share ceiling stood at 46.1% in 2016, and 46.8% in 2020, and his favorables are as terrible as ever. However, it also appears to be the case that Trump has a sturdy floor, and no amount of incoherence or combative rhetoric moves the populace much at this point. So, while it seems reasonable to conjecture that Trump will, for a third time, have trouble breaking out of his ceiling, his floor keeps him competitive.

Texas is not going to stop deploying wind and solar if Trump becomes President, and electric vehicle sales are not going to stop or even decline. Old coal plants will still retire. The current pipeline of new LNG export terminals, already approved, is not going to enjoy a particular boost from a Republican administration either. But acting as the executive, and because Trump has already threatened a broad tariff scheme, the White House could indeed throw monkey wrenches at imported solar panels, and other manufacturing and trade agreements that could slow progress. And remember, the US is not in a particularly good position anyway, right now, when it comes to lowering emissions further, because even the current Democratic administration has no current plan to thwart transportation sector emissions other than through EV adoption.

Perhaps the most important risk to consider is that Trump, through tariffs, mass deportation, disruption to relations with western allies, and through other governance errors could wind up introducing a form of economic instability that disturbs growth in general. Of particular concern is what affect his presidency would have on the interest rate market. A number of economists are worried both about the tariff plans, which could raise prices, and the tax cutting plans, which could over-stimulate the economy, resulting in higher interest rates. Indeed, the back-up in rates the past few weeks could be justifiably be interpreted as the bond market starting to price in such risks.

Sectors that have been looking forward to, if not counting on, lower interest rates are small cap stocks, renewable energy stocks, and housing related equities—not to mention the housing market itself. The US has had a successful exit from inflation (which was a worldwide phenomenon) and it would not be pretty, to say the least, if inflation were to return

The largest dam removal project in the United States is now complete, and salmon are returning to the Klamath River. The undertaking began several years ago, and took aim at four antiquated hydroelectric dams. The basic proposition: the economic benefits of river restoration would far outweigh the loss of hydroelectric output. Given the new volatility in hydroelectric power, and the fact that Oregon is now host to utility scale wind and solar farms, the downsides were minimal if not negligible. The Klamath begins its journey in southern Oregon, and emerges along the northern California coast.

Your faithful correspondent covered the story back in 2019. One of the more intriguing outcomes to the dam removal movement—which has been plugging along for more than 30 years now in the US—is that migratory fish tend to return to the rivers much sooner than expected. This is already happening on the Klamath. While full restoration will take years, it’s important to understand that these dams were nearly 100 years old, and that the river was at one time one of the largest salmon runs in the world.

Cold Eye Earth regards the dam removal movement as an excellent teaching platform to discuss the merits of human created infrastructure in the context of nature, and how nature performs crucial services to life on earth. Sometimes we do need to build things. Other times, the best return on investment is to simply hand back the keys to nature.

—Gregor Macdonald