Transition Depends on Trade

Monday 13 May 2024

A shadow has begun to fall across the project of energy transition in the United States. This dimming of the country’s decarbonization prospects comes at a time when many clean energy trajectories continue to do well. Solar capacity is taking off in Texas, battery capacity on the grid is exploding in California, and coal continues its steady retreat. Indeed, coal consumption fell so hard again last year that it actually made a dent in national energy emissions, which fell 2.7%. What’s not to like?

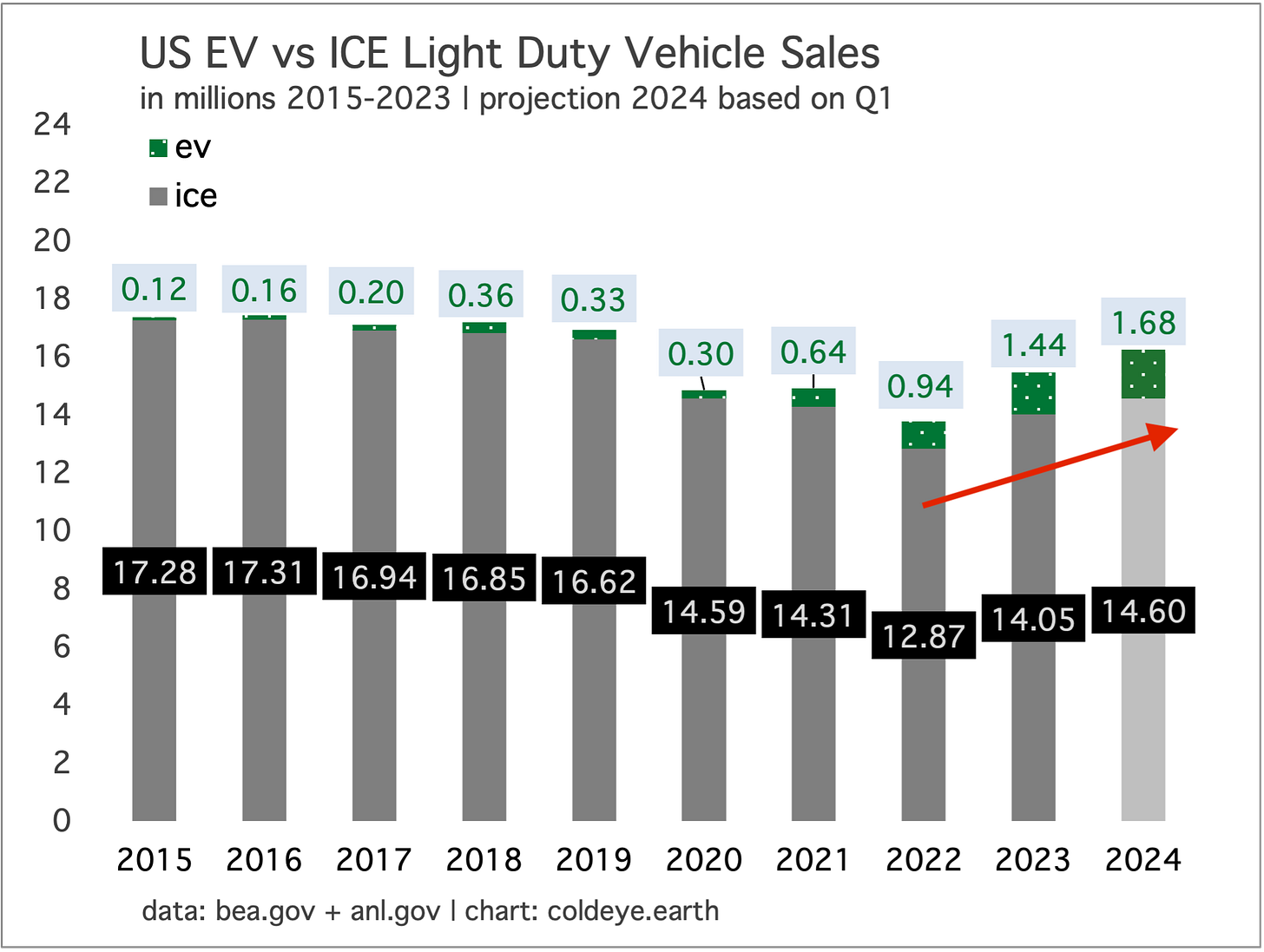

Let’s start with the transportation sector, because that’s where trouble has been brewing for a year or two, and now new roadblocks (sorry) to progress are appearing. You may recall for example that for the first time in six years, sales of internal combustion engine vehicles (ICE) rose in 2023. Yes, after six years of steady decline from a high of 17.306 million in 2016, ICE sales rebounded last year from a 2022 low of 12.872 million to 14.052 million in 2023, a 9% jump. Ouch. Double ouch. Those six straight years of decline were rightly considered the gateway to a sustained adoption of electric vehicles. How could it be otherwise? With Tesla in the lead, and despite a slow rollout of alternate models (slow compared to other markets, like Europe) EV adoption grew at robust rates during that period as Americans realized investing in an ICE car was a poor choice. And besides, trends that establish themselves for years like that have a tendency to not reverse.

Yet, ICE sales in the US are rising again for a second year. Through the first quarter of 2024, ICE sales are on pace to rise 4.3% this year, as EV sales slow down to a 17% growth rate compared to last year’s 53% increase. While it’s premature to call this an inflection point, it is not encouraging to see ICE sales bottom after a long decline. But this isn’t about Americans giving up or losing interest in EVs. Instead, it’s a problem with the market itself: the US simply doesn’t offer enough choices to consumers. Unlike the EV markets in China or Europe, the dearth of model choice has been a feature of the US market for years. How did we manage that constraint? Through the success of Tesla sales, mainly. Tesla single handedly papered over that problem as it took US national EV sales higher during the first extended wave of EV adoption.

The next part of the story you probably know well by now: US automakers fumbled the EV rollout badly. So, right at the very moment when US EV sales had gathered enough momentum to really start pressing higher into the 2022-2025 period, the market for the more expensive EVs finally saturated, and there were not enough automakers provisioning an affordable EV with acceptable range to the US market. Simply put: EV should be entirely dominating the US market by now, in 2024. Not only should the growth rates be higher, but sales should be strong enough to keep pressing downward forcefully on ICE sales, and ICE market share. Just to remind: EV market share is now heading above 30% in China, and above 20% in Europe. In the states, we’re only just starting to scratch at the 10% market share level. Here’s a compressed timeline of the fiasco, through the lens of General Motors:

2019: cancels the PHEV Volt just as consumers come to love it.

2020-2021: rolls out slick Ultium platform with TV commercials, saying GM will have 50 EV models by 2025.

2022: releases the EV Hummer, which currently retails for about $100,000.

2023: cancels the newly popular EV Bolt, just as consumers embrace it.

2024: decides to un-cancel the EV Bolt, but it won’t return until 2026.

Mary Barra: how do you like my black jacket?

In policyland, meanwhile, we know that an EV-only strategy is the convergence point that relieves elected representatives from the painful prospect of doing anything about the existing fleet of cars. As Cold Eye Earth has tediously remarked, your signal as to whether Americans genuinely want to tackle transport emissions can be gauged by the number of Democratic voters in big blue states that have demanded, and won, road-charging schemes, or other taxation schemes for existing on-road ICE vehicles.

This brings us to the broader, top down reality that US energy emissions have come exclusively through the successful war on coal. Emissions from natural gas have soared and continue to grow. Oil consumption meanwhile neither grows nor falls. Hence the shadow: now it appears that the US will fight cheap EV imports from China through 100% tariffs, and this comes on top of the Biden administration’s climbdown on aggressive emissions rules for automakers, and their future mix of ICE and EV offerings. Indeed, a cycle of retaliation seems to be setting in between the US and China, and the potential consequences could move far beyond the auto sector into everything from heat pumps to electrolysers, PV, and batteries. Readers may recall this chart from the IEA’s Energy Technology Report, as discussed in the letter last year:

Simply put: who makes all the stuff? China makes all the stuff. So what we’re seeing develop further in the US is that policymakers—whose first concerns are jobs—are increasingly likely to take further action against China. And that impulse is of course directly in opposition to a rapid energy transition. David Fickling, an Australia based writer for Bloomberg, put it well in his piece titled, Bans on Electric Cars and Solar Panels? It’s Not So Implausible:

China’s widening lead in clean technology, coupled with its vast trade surplus and Beijing’s desire to export its way out of a domestic slump, are combining with faltering efforts on decarbonization in developed countries to produce a toxic mix. If green technology such as electric vehicles, solar panels and home batteries gets badged as foreign and threatening and finds itself excluded via laws and tariff policies, then drastically falling costs aren’t going to be enough to get it into the hands of consumers. Spurious national security and industrial policy concerns will be sufficient to banish it.

Last week senator Sherrod Brown, who is facing a potentially tough reelection as a Democrat in Ohio, called for the banning of electric vehicles made in China. (Worse, Brown said he would join an effort to roll back EV tax credits). At the moment, this is of course just posturing. But as a weathervane it points in the direction of a political flashpoint. If cleantech is increasingly wrapped around the finger of geopolitical tensions, then the key components to decarbonization will become even more politicized than they are already, on the domestic level. Imagine, for example, if Europe had put tariffs on heat pumps prior to the partial blockade of natural gas from Russia. What came next—an enormous uptake of heat pumps in the EU that structurally lowered natural gas dependency—may never have happened.

The politically difficult reality is that comparative advantage is in alignment with environmental stewardship. It’s a form of efficiency which everyone likes, until they discover they don’t like its politics. The alternative is to pursue a far slower cleantech adoption regime that’s freighted with a heavy wish-list of political goals that will indeed, to use a European term, help with social cohesion. But, the price you will pay is a slower transition.

Let’s use a blunt example, one often cited by the political right in a clumsy attempt to crap all over the energy transition: China exports cleantech to the rest of the world from a manufacturing base that still largely runs on coal. Worth it? Absolutely worth it. The inventory of avoided emissions that can be realized through the cheapest solar, batteries, EV, heat pumps and electrolysers far outdistances the energy inputs—even if from mostly coal-power electricity—required to make those products.

While climate science is a complex discipline, lowering emissions follows elementary math. The United States has been successful so far in forcing just one of the three major fossil fuels into decline. There’s every reason to believe this will continue, as wind, solar, and battery growth remains solid in the US (though not spectacular). The question then becomes, what are either the policies, or, the technology price points that would finally get to work on the other two, US petroleum emissions and natural gas emissions? That’s what’s missing from the pipeline right now.

The US is essentially enjoying the payoff from a previous sequence of enacted policy. To conduct the next wave of transition requires a new combination of free-market price breakthroughs and policy-induced solutions. The public, and even many close observers, are quite mistaken if they think the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill (BIL), the CHIPS Act, or the Inflation Reduction Act are aimed at our petroleum dependency. They are not. And when it comes to natural gas, surely its use in the electricity system will eventually wane, but it hasn’t as yet, and that still leaves the 60% of US natural gas consumption left untouched, in the industrial sector.

As Cold Eye Earth has explained over the past year, the prospect that the US will reach its stated emissions goals by 2030—a 50% reduction from the highs of 2005—is completely off the table. For think tanks and other analytical groups still touting these goals as achievable, well, please stop doing that and sober up.

The Biden Administration’s infrastructure bills have neither caused inflation, nor have they crowded out private capital. US inflation was primarily a pandemic phenomenon as a collapse in supply was met head on by enormous stimulus programs into 2021. Those factors came through the pipeline, causing inflation to rise later in 2021 into a peak in 2022. Since that peak, labor markets have been tight, infrastructure spending has rolled out, and inflation has fallen steadily.

Quite obviously one of the more enduring misunderstandings of the public is the confusion over how spending bills actually work. They don’t roll out over 12 months. They tend, instead, to roll out over 120 months. Indeed, very little of the headline spending represented by the Infrastructure Bill (BIL), the CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act has been dispensed so far. Indeed, that part of the story was just reported by Ben Storrow of Politico.

One of the other old myths that appears to be making a comeback is the antiquated textbook idea that government spending will crowd out private capital. Sigh. This was tediously recited by Stanley Druckenmiller on CNBC recently and the idea is absurd in not just one, but two ways. First, infrastructure spending is rarely if ever activated by private capital. Private capital, in order to feel secure by investing in lower return projects, has historically needed the regulatory safety which only the state can provide. The US has been stuck in an infrastructure drought that has lasted nearly half a century, and at no point did private capital try to spark a revival because that’s simply not how it works. Druckenmiller is also wrong on the actual facts: the infrastructure bills have unleashed private capital. That’s right! The dollars coursing through the US economy right now behind new semiconductor and battery plants are largely composed of private capital that’s charging into the US on the back of government incentives. There is literally no argument from any quarter that this is not the case.

Billionaires on TV spouting economic nonsense have become a public nuisance. Literally the same cast of characters who decried the failure to invest in infrastructure during 2008-2020, are back to complain loudly, now that it’s happening.

Financial markets very much liked Fed Chairman Powell’s confidence that inflation will continue on its downward glidepath. At the FOMC press conference on Wednesday 1 May, Powell pointed out that inflation has been coming down all throughout the period that the US job market remained very strong, and he made it clear that he was far less concerned than observers expected over recent inflation readings. This predictably caused a number of commentators to accuse Powell of being unnecessarily dovish. But those retorts died a sudden death when the jobs report was released two days later, showing notable weakness. After hitting a high of 4.7% in late April, the yield on the 10 Year US Treasury has pulled back now to 4.5%.

If global electricity growth comes in slower than expected, and wind and solar keep growing at current rates, we may see power sector emissions finally decline. Something like this occurred last year, according to new data from London based Ember. Solar blew the doors off, growing by 444 GW of capacity, and wind growth slowed slightly but still carved out a new record high. But total global power growth came in under the historical rate of 2.68%, advancing just 2.20%. That enabled renewables to nearly cover all the marginal growth needed in global power, and that’s the holy grail. We want renewables to grow so fast that they not only cover all marginal growth, but they start to eat away at fossil fuels. We’re not there yet.

The problem still unsolved here is that in order to conduct energy transition we need to push the global electricity growth rate higher. It’s axiomatic. If you want to move the world’s economy to the powergrid, your powergrid has got to grow. If growth however had adhered to the historical rate in 2023, then renewables would have only slipped further away in covering the gap. Ember, for the second year in a row, sees peak emissions about to arrive in the global power sector. But Cold Eye Earth does not. Leaving the growth of renewables aside, readers are advised to think first about the global growth rate of total power sector demand. That’s the key number, and the growth rate we’re chasing. If that number comes in at a surprising low end, like it did last year, the momentum of wind, solar, and batteries will carry us over the finish line. But that should not be your expectation. Instead, it’s better to model a higher rate of total system demand growth, and then concentrate on the challenge that presents to renewables. This chart may help, as you think about those trajectories.

—Gregor Macdonald