The Commons

Monday 8 July 2024

The US Supreme Court’s overturning of the Chevron deference immediately weakens the regulatory power of US federal agencies like the E.P.A, regardless of which political party is in office. Accordingly, previously contemplated litigation risks that hover over future climate legislation have been brought into the present, and no longer turn on the outcome of the US election this November. The original landmark case, decided in 1984, laid the foundation for a strong administrative state as it acknowledged that federal agencies, not the courts, are institutions of expertise. The court at that time found, therefore, that uncertainties and ambiguities in law may be regarded as an implicit deference to agency decision-making, and, in the ensuing years the ability to legally challenge agency dominance was limited.

At the end of the Supreme Court’s term last month, however, this agency power was challenged by Loper Bright Enterprises, a fishing company operating in New England waters that says it was burdened by the financial cost of hosting a federal monitor program that protects against overfishing. In a 6-3 decision the court agreed, and terminated the precedent set 40 years ago. In the dissent by the minority, the decision was characterized as one that “will cause a massive shock to the legal system.” Thousands of cases rely on the 1984 Chevron decision. That case law has now been turned upside down.

But not only will the Loper Bright decision dredge up complications for these precedents, it will now shift decision-making away from agencies to courts. That re-weighting of power may have appealed to conservative judicial philosophy but its practical implications are quite messy. How can a judge determine best approaches to measuring and curing water contamination, or the creation of rules around workplace machinery? The systemic shock cited by the court’s dissenters implies, quite understandably, an explosion of litigation in a post Chevron world. One might call the court’s decision a make-work program for lawyers. (Just to say, law school enrollment stepped down to a lower level over a decade ago, so perhaps this heralds a recovery).

In a foreshadowing of the problems now looming from last month’s decision, the court in a separate case, Ohio v. EPA, blocked regulation from the EPA that sought to control air pollution from power plants and other industrial facilities. But Justice Gorsuch, writing for the majority repeatedly and incorrectly cited nitrous oxide as a key substance at issue in the case when in fact it is nitrogen oxide(s) that the EPA was trying to control. The former is known as laughing gas. The latter is part of the NOx family of gasses, most typically seen in any discussion or research on air pollution and smog especially. Oops.

One of the pathways new technology gains capability is through agency regulation, as older, less efficient, more polluting, higher risk incumbent methods are rendered uneconomic. There is an entire literature and historical record that demonstrates industry’s reluctance to bear the costs of modernizing products and services, but which demonstrates that the bulk of these regulations ultimately make industries more competitive. In other words, the regulatory state works to protect the commons. If you allow the commons to become a dumping ground, not only have you fouled your environment, but you have created a dependency in businesses who come to rely on not having to shoulder those costs.

Which brings us back to Loper Bright, a classic case of an agency trying to protect the commons. Indeed, it is hard to find a better example than the problem of overfishing, because the New England fishing industry was nearly destroyed late in the 20th century as fish stocks collapsed. In the past twenty years, however, environmental regulations have clearly been a big part of aquaculture’s revival in New England. Those muscles, clams, and oysters which in recent times grace the finest tables from Washington, DC to Boston are very much the result of the longer term effects of cleaning up coastal waters. The shellfish industry has exploded in size in the northeast the past twenty-five years.

When nature is protected, wealth is created.

Because wind, solar, and storage have largely passed through their early development stage and are now economically superior technologies, these changes to the power of the administrative state are not likely to blunt their growth. What the Loper Bright ruling does put back into play is the power of incumbency. If you’re an extractive business and you feel burdened by regulatory costs, you have a new friend in the Supreme Court of the US, and the lower courts will now craft their decisions on your claims in the light of the new framework. Meanwhile, if the dissenters are correct, the legal system may become quite clogged with such cases, and generally speaking enforcement doesn’t take place until a legal decision has been made. So, if in the future, the EPA doesn’t like the steps you’ve taken to control emissions from natural gas extraction or flaring, you can file a case against them as a plaintiff, and carry on for some time thereafter before any action is taken. We will probably see a flurry of such cases start to land soon.

Further reading: The Consequences of Loper Bright (July, 2024), Sunstein.

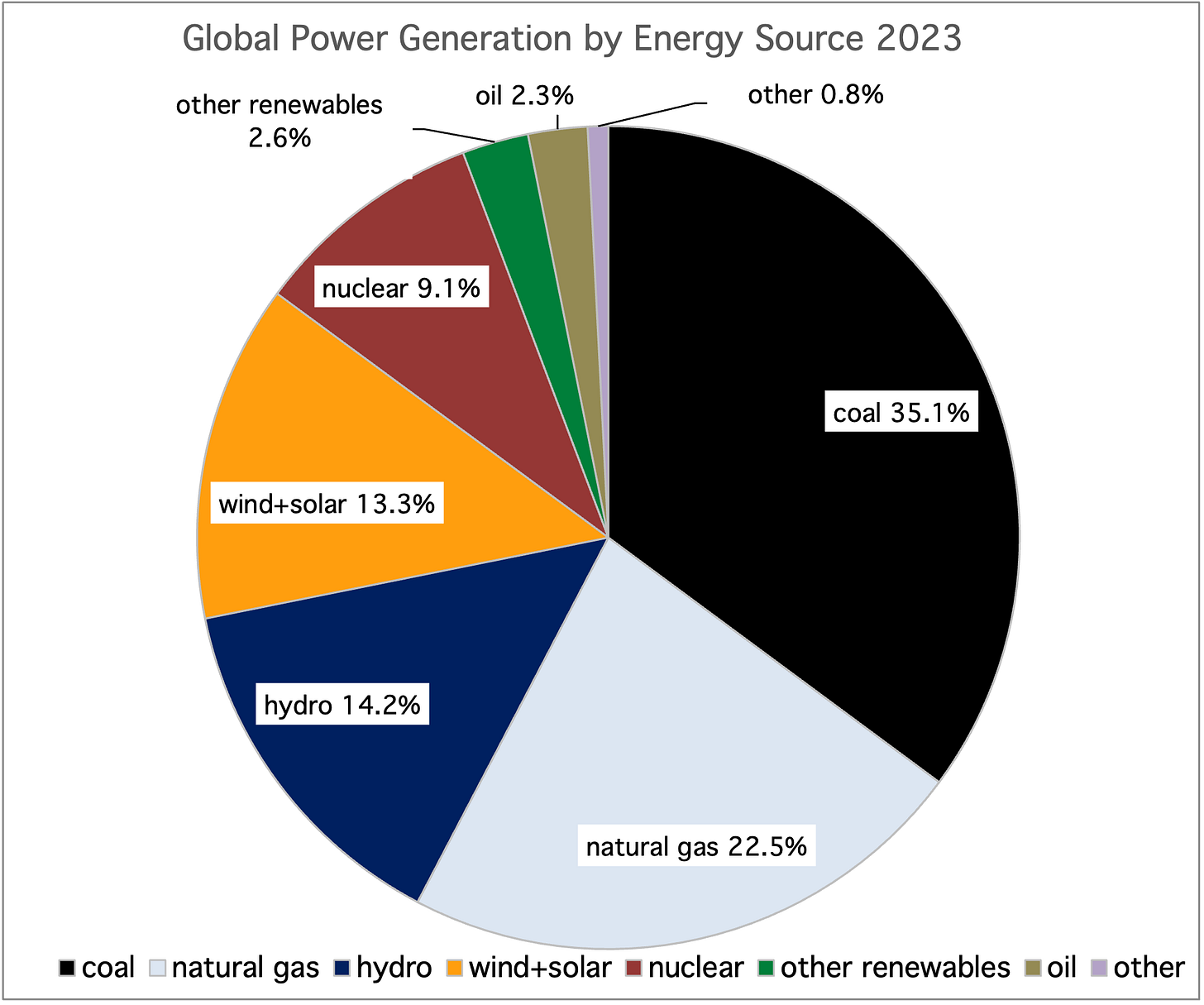

A two-year comparison of the global power system’s evolution reveals the fast growing threat to fossil-fuel’s market share. In the last issue of Cold Eye Earth, Global Power, we took a journey through the ongoing effort by renewables to catch fossil fuel growth in global electricity. While coal and natural gas continue to grow each year in absolute terms, their rate of growth has slowed. Reviewing these changes in market share terms, rather than in absolute terms, provides an additional lens to see the pressure being applied by the fast growth of wind and solar.

Over a two year period, from 2021 to 2023, both coal and natural gas each lost seven tenths (0.7) of a percentage point of market share, even though both continued to grow in absolute terms. Who grabbed that share? Wind and solar, which grew a full three points in just two years, advancing from 10.2% to 13.3% of share. For those of you familiar with competitive markets, you will immediately recognize that gaining three points of market share in an enormously large system is seriously impressive. For incumbents, it’s also a warning.

While the growth of wind and solar is both strong, and increasingly stable, two clean energy allies in the mix are presenting challenges: hydro, and nuclear. We can’t afford to lose market share from these two technologies. The former is being knocked around by a more extreme, climate-change led volatility in drought and deluge, while the latter suffers from fleet retirements. (Cold Eye Earth has advocated for years now that the world needs to build some new nuclear, in a context where we all acknowledge that wind, solar, and storage will primarily lead the way. Nuclear absolutely cannot solve the problem alone, but it would greatly help in a junior, supportive role. The loss of seven tenths (0.7) of nuclear’s market share over two years is bad).

On the encouraging side of the landscape, if you sum all the dirty sources (natural gas, coal, other, and oil) you’ll see they lost 1.6 percentage points from 2021 to 2023, as collectively they fell from 61.58% to 59.98% share. In the small category, the reduction of oil’s share in global power from 2.5% to 2.3% may seem tiny—but it helped! Oil is a weird artifact of the early days of electricity, and many islands around the world still use it to make electricity—something that’s being overturned now by wind and solar. (Greece is a great example of this storyline).

This might be a good time to remind readers who don’t work with statistics all day that we are discussing market share, here. Not absolute growth or decline. For example, oil has fallen from a 50% market share of total global energy in the 1970’s to nearly 30% in recent years—but oil consumption in absolute terms was rising all that time. There are multiple examples of how system growth can be harder to see for people, as they inspect changes within systems on a shorter term basis. For example, let’s say you are trying to reduce math illiteracy in a fast growing urban school system from a level of 10%. Well, you may succeed in getting that down to 8% then 7% over time but the total number of students in the category may actually be rising as population (starting from a big base) grows even more.

This is why Cold Eye Earth keeps hammering away at the flurry of reports from clean energy advocates which rarely if ever mention or model systemic growth. It pains me to say it, but, spectacular growth of clean energy resources is simply not a case-closed argument that we are successfully decarbonizing, because the system itself is bloody enormous and only has to grow by 1-3% percent each year to make it tough to catch.

All data comes from the recently released EI Statistical Review.

Fourteen years of Conservative rule have come to an end in the UK. But only after the British people fell for two, well-established and very damaging economic myths: austerity and restricted trade. Labour’s landslide victory on the 4th of July, along with other recent polling on Brexit and the country’s economic stagnation, confirms the populace now understands these two rather massive mistakes. What’s particularly ironic about this storyline is that Britain is the country which originally produced the landmark economic theories that specifically address both austerity and trade policy. The reference of course is to John Maynard Keynes and his predecessor, David Ricardo.

There’s not enough white space here to delve too deep into the full works of these economists, but briefly: Keynes recognized the dangerous trap of austerity; and Ricardo uncovered the folly of tariffs, and the potential power that could be unleashed by free trade. Keynes’ position against austerity was mild compared to the great unleashing of money now overseen by central banks during crises, but his views on this matter are summarized nicely in his quote, “The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.” Ricardo meanwhile made an equally important discovery, showing that free trade not only utilizes advantages that country Y may possess over country Z, but in doing so, economies and markets in both country Y and country Z will benefit. Ricardo saw that through free trade, the total size of the economic pie actually grows.

David Cameron and the Conservative Party chose austerity as the best policy to address the after effects of the great recession. In doing so, he and his party set the UK on course for a decade of astounding underperformance. We can think of austerity therefore as a highly effective method to ensure your economy not only fails to recover, but changes course to a lower, and weaker trajectory. Who better to reckon with that record than the Financial Times of London:

Does anyone study economics anymore? Just to strengthen the case, let’s recall that the first four years (at least) of the Obama administration also saw very weak, plodding growth because apart from monetary injections into the economy, the US congress, controlled by Republicans, also made sure that any fiscal help was constrained. The right response in both countries would have been a full-throated Keynesian program of fiscal spending on infrastructure.

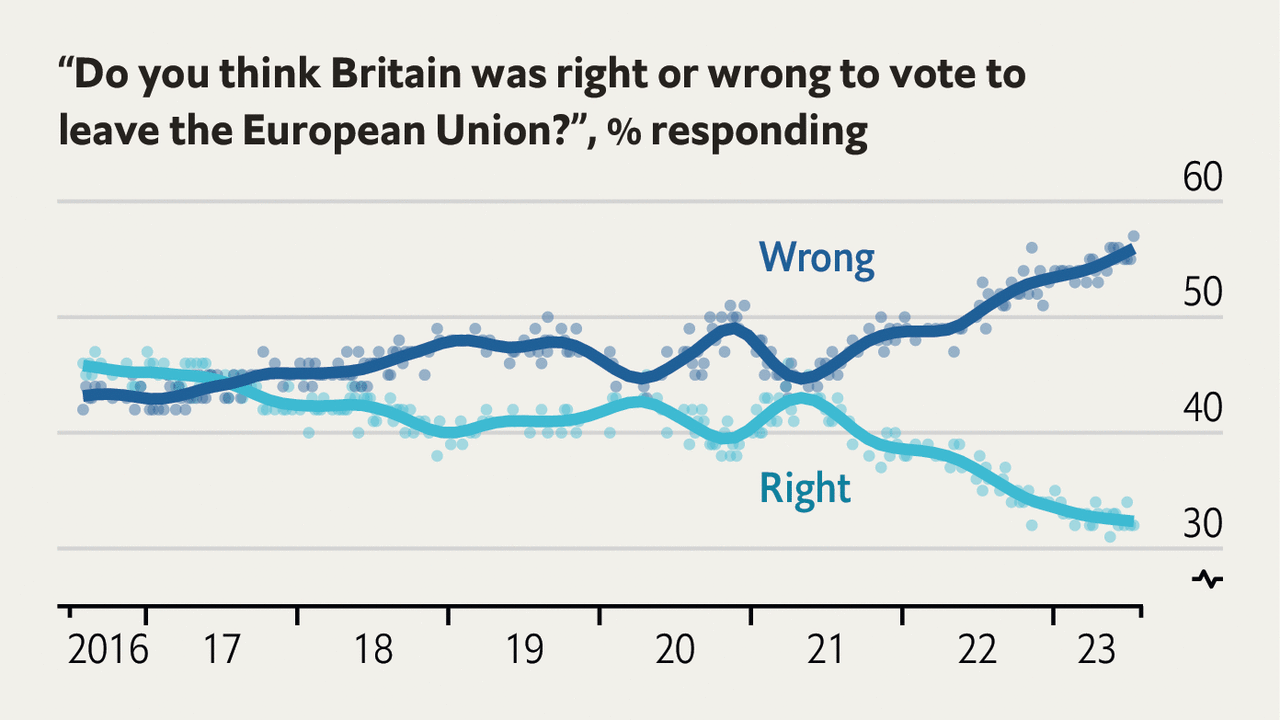

Britain therefore was in full possession of the knowledge to understand that austerity wouldn’t work. One big mistake was not enough, however. Cameron later in the decade would conduct a referendum on Brexit—a truly crazy and self-destructive idea—and after that passed, Britain set about undoing all the benefits it had gained from entering the common market at the turn of the century. Once again, all the knowledge necessary was available to avoid this own-goal. It must be said: interviews with voters demonstrated repeatedly that most were voting in favor of Brexit for the most blinkered and parochial reasons. Let’s see what they think now:

That’s a chart published in The Economist one year ago this month, and is now more easily discerned as a warning to the incumbent party. Britain’s last election was five years ago in 2019, and views about Brexit at that time were not as polarized. One explanation: the pandemic saw strong Keynesian policies enacted in the US which were a success. In Britain, the country not only got the inflation, but didn’t get a recovery either.

Yes, Britain eventually was able to get going again, but only moderately by late last year. By then of course, so much damage had been done it was inevitable that whomever was responsible for these conditions would be voted out.

But let’s not blame everything on the ousted politicians. They were voted into office repeatedly. Moreover, the results of the recent elections show that because the Reform party split the vote with the Conservatives—which opened a wide channel through which many Labour seats were gained—the popular vote could be seen as a far less enthusiastic endorsement for any broad move to the left. But leaving aside right vs left questions, it’s clear the public has had enough. And if Labour is able to deliver, we may find that it’s not so much the right vs left dynamic that is supreme, but rather, a return to better economic conditions that wins the day.

• Further reading: for the best precis of all time on Ricardo, please see this Krugman classic, which has thankfully been up on an MIT website for years: Ricardo’s Difficult Idea.

Global emissions from energy rose 1.6% last year. This is roughly in line with the data showing that fossil fuel consumption rose by 7.37 EJ, or 1.5%. The result suggests neither improvement nor deterioration in the fight against emissions. Just as in the global power system, total global energy is also enjoying the rapid buildout of renewables. But total energy consumption also advances from a very high base, which means that its forward march in absolute terms is enormous. Renewables so far, therefore, are still not able to keep up. Until they do, not only will we not be at peak emissions, but emissions will keep growing.

Sorry to pound the table on this again: but every time you read a thinktank’s prediction of future emissions, if that forecast does not include a grading of renewables growth against total system growth, then feel free to ignore it.

Last year, clean sources grew by a net 4.91 EJ, as compared with the previously cited year-over-year growth figure for dirty sources, at 7.37 EJ. You can probably just eyeball both numbers, and see that of the total advance last year of 12.3 EJ clean sources took 40% of the world’s energy growth, the other 60% taken by fossil fuels. That’s exceptionally encouraging, and discouraging, at the same time!

News Briefs: “Trying to use tariffs to fund the US government is not only mathematically implausible but also raises all sorts of practical problems and economic uncertainties,” says a new report from the Cato Institute, in reaction to Trump’s suggested plan to erect a massive tariff scheme: Trump’s Latest Tariff Idea is Dangerously Foolish. • The IEA says SUVs were responsible for over 20% of the growth in global energy-related CO2 emissions last year. Worse, the heavy vehicle class now accounts for nearly half of all global auto sales. • Plug-in hybrid sales are experiencing a revival, perhaps as a result of consumers looking for more affordable range. The head of BloombergNEF’s clean transport research has an excellent update with charts and data at Twitter. • Friday’s jobs report was solid at 206,000 but the previous two months were revised downward, and a discernible weakening trend, while early, is starting to form. This led many market observers to opine that the FOMC needed to get started soon on rate cuts, to remove the excess tightness in Fed funds. • The futures market which covers Fed funds restored a second rate cut to the 2024 outlook, after Friday’s jobs report. See the FedWatch Tool at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. • Neil Dutta of Renaissance Macro feels the Fed is getting closer to making a policy mistake, if it does not cut soon. Hear the interview at the OddLots podcast. • The global macro research team at Goldman Sachs is starting to ask an important question when it comes to AI investment: when will all the capex transform into profits? •

—Gregor Macdonald